Meet the Oklahoma flapper who wowed crowds with 18 instruments — while escaping a notorious past

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Loma Worth was defiant.

The daughter of a notorious Oklahoma millionaire abandoned her old life years earlier and was making her big return as a Vaudeville performer while disavowing her original name, Olive Belle Hamon.

In her return home to Oklahoma, she was already known as “Miss Versatility” based on her performances as a musician, singer, performer, pioneer aviator and one who embraced taking on challenges that would have intimidated men and women of her time.

Without the scandalous back story that captivated an entire nation, this was a woman whose talent, including playing 18 instruments, made her a popular headliner in the vaudeville era.

Oklahoman reporter T.T. Johnson scored an interview and dared to ask Worth about the murder of her father, Jake Hamon, a man of wealth and power a decade earlier when she was just a girl.

“I stand on my own feet,” Worth responded. “My father did nothing for me. I don’t know him! I am paying my own way, and I don’t want to drag that scandal after me the rest of my life!”

More: This historic home in downtown Norman was where UCO's Broncho mascot began

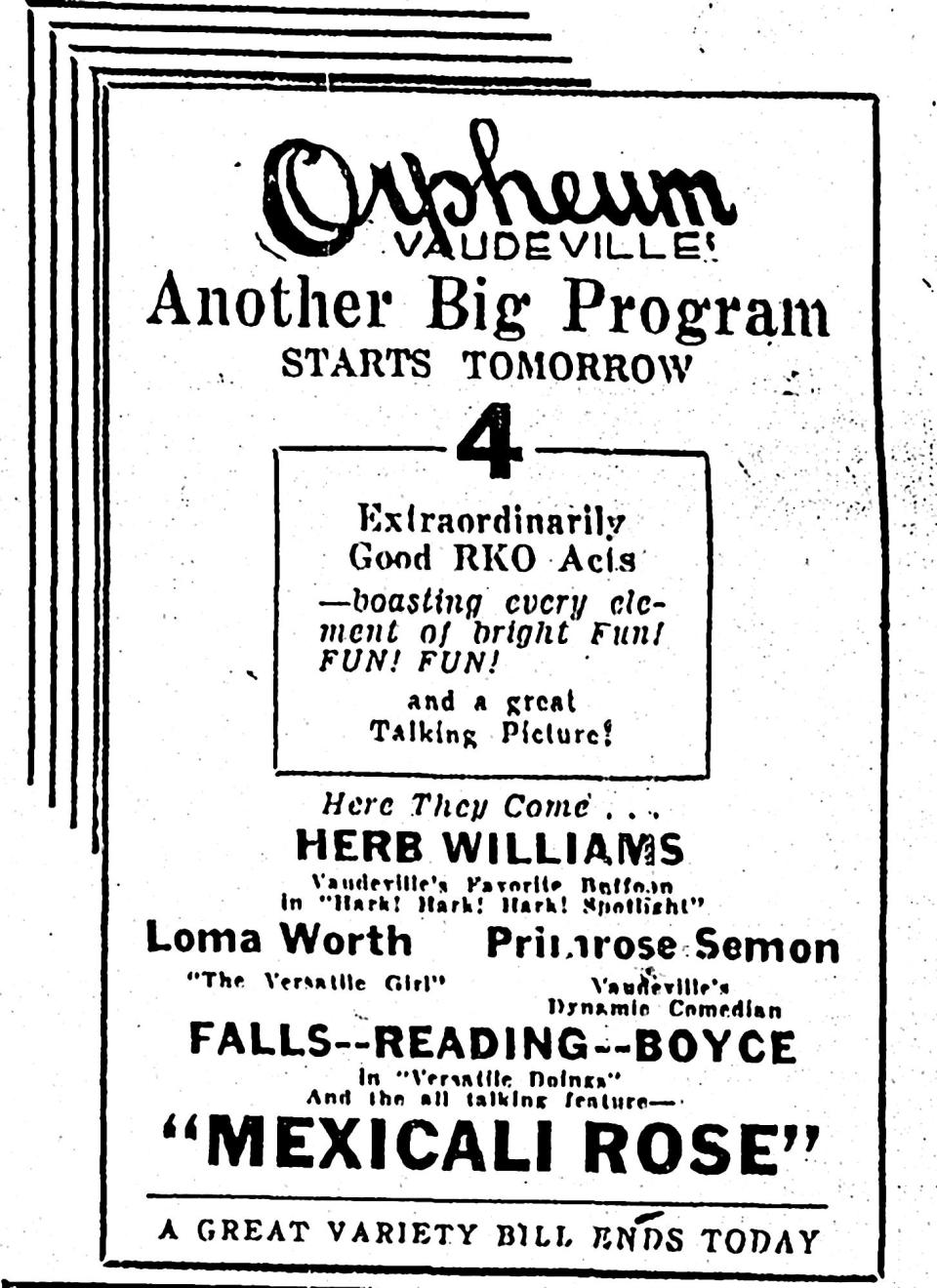

It was early 1930 and Worth was in the midst of a weeklong appearance at Oklahoma City’s Orpheum Theater. Johnson kept up with the questioning. Worth had just wrapped up her first performance, including three encores, with a “staccato renunciation” of her past, her old name and any connection to Jack Hamon.

“Through some misinformation,” she told the audience, “newspapers have published reports that I am related to a man who lived in this state. His name — er — I believe was — er — Hamon. The reports are incorrect, and I do not wish you to be deceived. My home is in Fort Worth and my name is taken from that.”

The denial was bewildering for some. Wasn’t this the Olive Belle Hamon, the child prodigy who at age 14 climbed a fire escape to the top of a 33-story building in Chicago — while playing a violin the entire time before a news camera? Wasn’t this the Olive Hamon who had made a name as a daredevil pilot, Vaudeville entertainer and scandal sheet mainstay?

In her dressing room, wearing what Johnson described as “lashes beaded to the size of buckshot, and clad in a costume of a closely fitted bodice and tights,” Hamon insisted she be called Loma Worth. It was an awkward visit as her mother, Georgia Hamon, listened as the entertainer spoke with Johnson and explained why the announcement was made.

More: Hints of history of gambling, booze and vice still to be found at former Kentucky Club

“You are making me appear in a bad light,” Georgia Hamon rebuked her daughter. “After all you are my daughter, and Jake Hamon was my husband. What is your name?”

Worth laughed at her with a response described as “terse and peppered with wit.”

“What is my name?” Worth replied. “Oh, what does it matter? Anything. Lizzie Finkle. And you can be Mrs. Finkle, except when you collect my salary. Then you must be Mrs. Worth.”

Olive Hamon, aka Loma Worth or Lizzie Finkle, was not going to be defined by a name or the scandal that filled the pages of newspapers and gossip tabloids nationwide.

Extortion, bribery, politics, murder and scandal

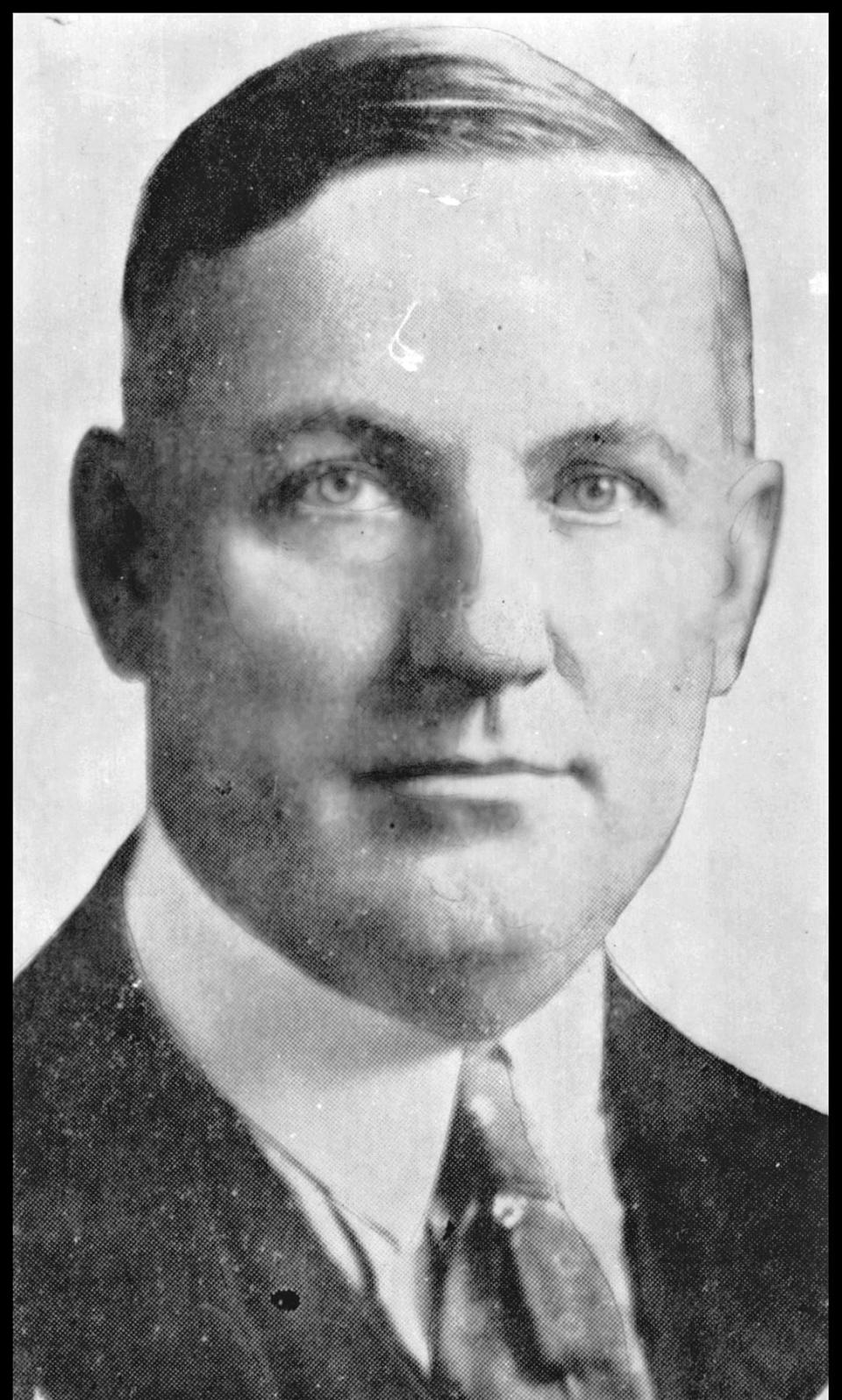

Despite her denials, Worth was born as Olive Belle in 1909. Her father, Jake, arrived in Oklahoma Territory in 1901 and served as Lawton’s first city attorney. He was an entrepreneur who dabbled in oil and teamed up with circus legend John Ringling to build a railroad.

From the start, Jake Hamon was accused of extorting money from gamblers, and he was ousted from office in 1903. A few years later, Sen. Thomas Gore proclaimed during Senate session that Hamon attempted to bribe him over sale contracts with the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations.

His reputation of corruption, however, wasn’t a problem for Hamon’s rise to join the equally shady Cabinet of President-elect Warren G. Harding in 1920. Former Oklahoman reporter Ron Jackson, who in 2013 authored a history of the scandal, noted political insiders at the time had credited Hamon with using his money and political muscle to secure Harding the party nomination months earlier, thus paving his road to the White House.

Harding was expected to return the favor.

More: Still standing: The legacy and history of an Oklahoma Rosenwald school

Jake Hamon’s home life, however, was in shambles. After carrying on an affair with Clara Smith, a 16-year-old store clerk, he paid his nephew $10,000 to marry the girl and then disappear to San Francisco. In his story about Hamon, Jackson wrote that the bogus marriage gave Clara the Hamon name, and allowed her and Jake to travel as a couple with a facade of legitimacy.

Hamon's abandonment of his wife was still quite public.

Georgia Hamon initially fought for her husband, confronting Clara and even Clara's mother, Jackson wrote. Georgia Hamon's pleas were ignored. She eventually left the state with her two children and ended up living in Chicago. Yet, she refused to grant her husband a divorce, and the charade continued.

At the center of it all sat a pile of money that would long haunt Olive Hamon, or, ahem, Loma Worth.

Olive Belle was 11 years old when her father staggered down the stairway at the plush Randol Hotel in Ardmore on the night of Nov. 21, 1920, wincing and clutching his right side. Bob Hutchins — Hamon's friend and bodyguard — rushed toward his boss.

'Tell the senate about Daddy'

As he was taken to the Ardmore Sanitorium and Hospital, Jake Hamon claimed he had accidentally shot himself while cleaning a pistol.

With his appointment to the Harding administration already widely anticipated, news of the accidental shooting soon splashed across newspaper pages nationwide.

The bullet was lodged against Hamon’s spine. Five days later, Hamon was dead, and the true story that emerged was far uglier and scandalous than what he had portrayed.

The manager at the Randol Hotel testified that Hamon was drunk “as usual.” Clara, the girl who was only a few years older than Olive, claimed Jake had been acting “beastly” and injured her with “ugly names.”

Hutchins contended Clara had been “hitting the bottle” heavily, distraught over the fact she would not be going with Hamon to Washington, D.C. The Harding administration wanted Hamon to reunite with his family and to leave his “secretary” back in Oklahoma.

Just before the shooting, Harding's confidants were in town to chat with Hamon about the role he would play in the administration, and Hamon planned a special supper. Two wild ducks were shot and prepared for the occasion, but Clara was not invited to the dinner party. She showed up anyway — drunk.

Hutchins claimed Jake Hamon and his young mistress argued at the dinner table before she hurled a duck at his face. Hamon ordered her upstairs, and even threatened to call the police and have her arrested for disorderly conduct. Hutchins seized Clara and escorted her to her room, where she supposedly fell asleep.

Hamon told Hutchins he would slip up to her room later to console her, confessing he had been mean to her.

“Jake,” Hutchins warned, “don't go up there at all. I have been watching what has been going on here today. Your political enemies are striking at you through her. She is all torn up because you are going to Washington without her. She thinks you are giving her the brush-off. If you go up there now, you will come down on a death wagon.”

Hamon ignored the warning. No matter what story was true, Hamon was shot and those bullets ended decades of bribery and king-making.

The last witness in the murder trial was Jake Hamon’s estranged wife, Georgia. In a history about the Tea Pot Dome scandal that soon after consumed the Harding presidency, author Laton McCartney detailed how Georgia and Olive had visited the “love nest” Jake Hamon shared with Clara at the Randol Hotel.

On one of the visits, Georgia looked into Clara’s closet and saw the young woman’s clothes and fur coat. “After I had grown old — old before my time — she came along with her beauty and insulted me by parading my husband,” she said, breaking into tears.

Clara was found not guilty. Georgia, Olive and her brother, Jake Hamon Jr., were to each get a portion of an estate initially valued at $13 million and later, after assets were determined to be overvalued, at $3.1 million.

But was it really worth even that much? Hamon, according to reporters, owed $1 million to National City Bank of New York. Scandal sheets claimed Georgia Hamon herself blew through the money living beyond her means.

Olive didn’t immediately turn against her father. At age 16, she ran away from home and traveled to Washington, D.C., in 1922 as the U.S. Senate was delving into the Tea Pot Dome scandal involving Harding and a multitude of associates, including the late Jake Hamon.

Stepping out of a train from Chicago, violin case at her side, Olive told reporters she was in town to “tell the senate about Daddy.”

The day before she had left a note with her mother saying she was traveling to tell senators her father had engaged in bribery, but had not offered to trade support for a presidential candidate in exchange for a Cabinet post.

“I just felt Daddy would want me to tell the senators that it wasn’t true,” she explained before she was whisked away by her mother’s cousin.

Either way, still a teenager after the trial, Olive went to work.

She spent the next few years making her way in the world, hitting the vaudeville circuit, doing publicity stunts like climbing the fire escape in Chicago with the news cameras rolling.

“Put yourself in my place,” Olive Hamon argued in the 1930 interview with The Oklahoman. “I am paying my own way. My father did nothing for me. I don’t want to be made notorious for his acts. He may have been a big shot in Oklahoma. He may have been a very nice man. He may have done great things. But to me he is nothing! Absolutely nothing! I hardly remember him.”

The reporter with The Oklahoman then asked, “Who paid for your music lessons?"

“My father had me take violin,” Olive responded. “He did pay for that when I was a little girl. But I’ve paid for the rest of them. And I haven’t a college education like other girls. This isn’t my chosen profession, you know?”

“Do you have to work?” the reporter asked. “Didn’t you inherit a large sum of money?”

“Ha!” she exclaimed. “That’s what everyone thinks. We didn’t get any money. When the estate was settled we were broke.”

So, what was her career choice?

“I want to be a newspaper woman,” Olive said. “I was once. It was in Chicago. I was 14 and I got a job as flapper reporter on the Chicago American. I covered the Leob-Leopold trial from a flapper angle and met all the murderers. It was great fun. But I was fired. I used too many taxis and ran up expenses.”

Over the next couple of years Olive was flying her way from state to state and to destinations as far away as Canada. Reporters referred to her as the country’s first flying vaudeville artist. During a Pennsylvania stop, she told reporters her love of flying started during a visit in St. Paul, Minnesota, when she was taken for a flight. During another stop in London, at the age of 21, she told reporters she had already racked up 160 hours of flying time.

Her brother, Jake Hamon Jr., skipped politics and fame. He went into the oil business and was a successful businessman who in later years was friends with President George H.W. Bush.

Olive, meanwhile, spent the 1930s touring a dying vaudeville circuit and staying in the headlines as she toyed with one marriage proposal after another before attempting and ending multiple unions.

In 1932, gossip columnists tied her to not one but four suitors at once, including prominent newspaper cartoonist Pedro M. “Pete” Llanuza.

The Seattle Daily Times summed up the race for its readers:

“The merry-go-round marriage mystery, who will wed Olive Belle Hamon, got dizzier today,” the newspaper shared. “Not only did the daughter of the murdered Jake Hamon, famous Oklahoma oil magnate, steal away from her mother to lunch with the young man of her heart’s choice, but a third and then a fourth suitor entered the whirligig race.

“As the altar racers entered the stretch they lined up with Forrest C. Cross, 28 years old, still in front with a license to marry the girl; Pedro Llanuza, 52-year-old newspaper cartoonist, who tried vainly to get a license, still intent on marriage; a mysterious Larry, one on a self-confessed three-day drunk because he can’t marry Olive Belle, known to the vaudeville stage as Loma Worth, and a Manhattan physician, a hopeful outsider….

… “Cross, an ex-Marine, got a license to marry the blond and bejeweled Olive Belle Thursday, and Llanuza tried his best to get another license Friday, only to be balked because he did not have his divorce papers….

…“I still think my little girl ought to marry Mr. Llanuza, although it is true he is very dictatorial — men are always that way,” the mother said, reflectively. During the day she had some telephone conferences with Llanuza.

“The cartoonist was still intent on rushing the actress to the altar as soon as his divorce papers arrive from Illinois. Mrs. Worth (Georgia Hamon) said that over the week-end she intended to have Llanuza meet Cross so that they could discuss their common interests.”

Hamon continued to perform across the country, and in 1935 she shared a stage with an "all girl revue" that included a young Shirley Temple just as the child actress was on the verge of becoming an international movie star. In some promotions Hamon was billed as "America's musical sweetheart" and in others she was called a "one girl band."

The Orpheum vaudeville circuit, which hosted Hamon at dozens of its theaters, went bankrupt in 1931. The Orpheum in Oklahoma City was turned into a movie cinema and renamed Warner Theater.

As vaudeville came to an end, so did the headlines for Olive Hamon. The last mention of "Loma Worth" was in a 1937 announcement that featured a photo of her playing a horn and announcing she was resuming a performance tour. The same clipping, oddly, identified her mother as "Miss Josephine Worth" of Hackensack, N.J.

In the end, whether by plan or not, Olive reunited with her family. She died in 1987 at age 77 in Portland, Oregon, and was buried at Rose Hill Cemetery beside brother Jake Jr. and parents Jake and Georgia Hamon. Defiant to the end, however, her name on the gravestone is “Loma,” not Olive.

Steve Lackmeyer started at The Oklahoman in 1990. He is an award-winning reporter, columnist and author who covers transportation, downtown Oklahoma City, urban development and economics for The Oklahoman. Contact him at slackmeyer@oklahoman.com. Please support his work and that of other Oklahoman journalists by purchasing a subscription today at subscribe.oklahoman.com.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: 1920s flapper wowed audiences, overcame scandal and then disappeared