Meet the residents of Brooklyn’s greenest block. Here’s how they did it

At first glance, Lincoln Place looks a lot like streets in Brooklyn: wide brownstone stoops, dog-walkers and stroller-pushers, double-parked delivery trucks.

But hang out for a while and you’ll notice that the block, a stone’s throw from Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights, is an oasis of trees, plants and flowers.

Welcome to the greenest block in Brooklyn, an accolade that Lincoln Place has now earned twice in Brooklyn Botanic Garden’s long-running competition to foster more gardening in the city.

Lincoln Place’s forces of nature are Perri Edwards and Althea Joseph, next-door neighbours and friends whose shared love of gardening led them to create an ad hoc group PLANT – “Preserving Lincoln’s Abundant Natural Treasures”.

“We started the group so we could bring the neighbours together,” Joseph, a retired fashion designer, told The Independent. “It’s a changing dynamic with properties being sold, different cultures coming in, kids being born. We wanted to unite both young and old and give an opportunity to be part of what we do.”

Neighbours have clearly risen to the challenge. Along with its flourishing 27 tree beds, Lincoln Place is lush with roses, ferns, ivy, gardenias and elephant ears, not to mention the tomato plants and an entire “kitchen garden” of herbs.

“It’s a hobby that I like to say ran amok,” Edwards quipped.

Lincoln Place, between Nostrand and New York Avenues, first won the greenest block title in 2019 before the contest was paused in 2020 due to the Covid pandemic. In 2021, the contest was adapted to a “window-box only” format.

“There was a lull during Covid but we still planted,” Joseph said. “People love coming through because it is such a peaceful place.”

They have taken part in workshops at Brooklyn Botanic Gardens which help residents learn how to green their blocks.

“The first workshop that I went to, I realised everything I was doing for my tree was wrong and I came home and immediately changed,” Edwards said.

“The whole project is about caring for the trees. The key element is the trees,” Joseph adds.

The competition returned in full this summer. Lincoln Place beat dozens of other blocks based on their plant variety, sustainability, quality of gardening and level of community involvement in a “Plants meet Art”-themed entry.

Their winning concept in 2019 was “Welcome to the Circus”. (“Perri built a carousel with little popcorn boxes. I had to do a Ferris wheel but I bought it from Wayfair,” Joseph confided).

“We’re big on upcycling, we love to find things and make them into planters,” says Edwards, who recently retired from a career in law enforcement, but has inherited the creative flair of her artist father. “I made planters out of laundry detergents, milk containers, BBQ grills.”

Near the curb, a tire has been spray-painted with a sunny yellow colour and forms the base of a plant pot. A defunct bicycle was decked out with wineboxes to hold flowers. The artwork that has been incorporated through a lot of the gardening is “opening a lot of conversation,” she added.

At her house, Edwards has a “kitchen garden” with pots of herbs, ladles turned into mini planters and even an antique stove picked up from the nonprofit salvage store, Big ReUse. In the center is a lectern with The New York Times obituary for her mother, Grace Edwards, a mystery novelist and former director of the Harlem Writers Guild, who died in 2020.

Joseph’s garden is influenced by her fashion career with a mannequin draped in beads, mirror and dressing table. It also pays tribute to her mother, Lucille Dolloway, an avid gardener who died within months of Ms Edwards. One of Ms Dolloway’s poems is attached to the railing along with her favorite flower, a dahlia.

Joseph says that she’s not a natural green thumb. “We learned from the little stickers on the plants, from each other, from the neighbors. YouTube, Google. It’s a learning process to plant.”

Now, the residents of Lincoln Place are advising others. New Yorkers from surrounding boroughs have come to investigate along with others from further afield for tips and mentorship. “We had a couple that just came from Philadelphia,” Edwards said.

Along with the rest of the block, family members have gotten involved. Both of their granddaughters planted cherry tomatoes in containers from the local pizza shop. Joseph’s son, a graphic designer, made their sign and logo. One music-loving neighbor has added tributes to the Rolling Stones and Joni Mitchell in his garden. An artist who live on the block, Alex Bodnar, painted large, colourful portraits which have been incorporated into the greenery. Children have decorated stones for the tree beds with messages like “Be Kind” and “Hope”.

Apart from a grant of a few thousand dollars from the non-profit, Citizens Committee for New York City, the residents fund their gardening projects, bolstered by block party fundraisers. “We would like our local government to give us grants,” Edwards noted.

The PLANT ladies have hosted baby showers, holiday gatherings, and hold “snack and chat” meets for neighbors to talk and mingle. Their next event in September is themed “Culture Meets Art”.

“I think art opens the door for culture to talk,” Joseph said, adding that they plan to have food, live music and children’s games.

She recalled: “One day I heard this beautiful violin music. It was our neighbor Alison who said her friends were fooling around in their quartet. I said, ‘Could you fool around on the 10th?’”

While the residents of Lincoln Place wear their achievements lightly, there’s serious benefits to what they have created.

Cities, particularly large and densely populated ones like New York, face a reckoning in the coming years as the climate crisis leads to more frequent and intense heatwaves.

The volume of manmade materials, along with heat-pumping machines like air conditioning units and cars, can leave cities with afternoon temperatures 15-20 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than rural locations, says the National Integrated Heat Health Information System.

Extreme and sustained heatwaves have gripped nearly every part of the US this summer. New York has face repeated rounds of stifling heat and temperatures nearing 100F, with nights bringing little respite.

It’s something that the Lincoln Place gardeners are acutely aware of.

“We feel that climate change is a really big issue and this is why we take care of the tree beds. It’s much cooler than other blocks. Neighbors and strangers have told us the same thing,” Edwards said.

High temperatures don’t just leave residents feeling grumpy and uncomfortable. Intense heat, particularly when combined with high humidity, can lead to serious illnesses, and even be fatal. Some groups are more susceptible to risks like the elderly, young children and those with underlying health problems. Low-income communities and people of colour are also more likely to live in hotter neighborhoods, according to a 2020 study.

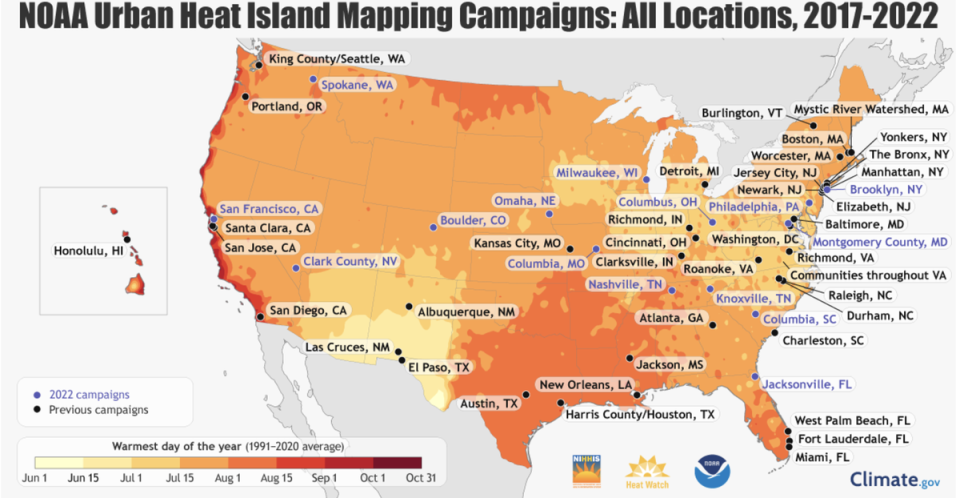

The Biden administration recently launched a website focused on extreme heat, the US’s biggest disaster-related killer, with details of the ongoing project to map urban heat islands. Residents of upper Manhattan and the south Bronx took part last year and discovered a 7.5-degree difference between some areas during peak afternoon heat. Brooklyn is part of the 2022 campaign.

Knowing where hot zones exist is key to pinpointing strategies to cool things down. These can include coating heat-absorbing dark surfaces with “cool”, reflective paint, creating more public spaces that have access to air conditioning and improving natural ventilation in buildings.

Nature is another ally to beat the heat. Trees and plants not only provide shade but absorb and release moisture through a process called evapotranspiration which cools the surrounding air.

At the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens, one workshop showed local residents how to set up drip irrigation in tree beds – placing a lidded container or bucket with tiny holes to allow water to trickle through, and keep the soil moist.

Edwards was one of those who attended. “I even put inches inside so that I can keep track of how much water comes out,” she said.

And, of course, on Lincoln Place those drip irrigation containers have been “funked up” with art.

“Last summer when it was extremely hot, people preferred to walk on this block than on Eastern Parkway or any other block, “Joseph says.

“We’re always on this block so we take it for granted but when we leave this block and go somewhere else, we feel it. It makes a big difference.”