Meet the Woman Using Magic Mushrooms for End-of-Life Anxiety

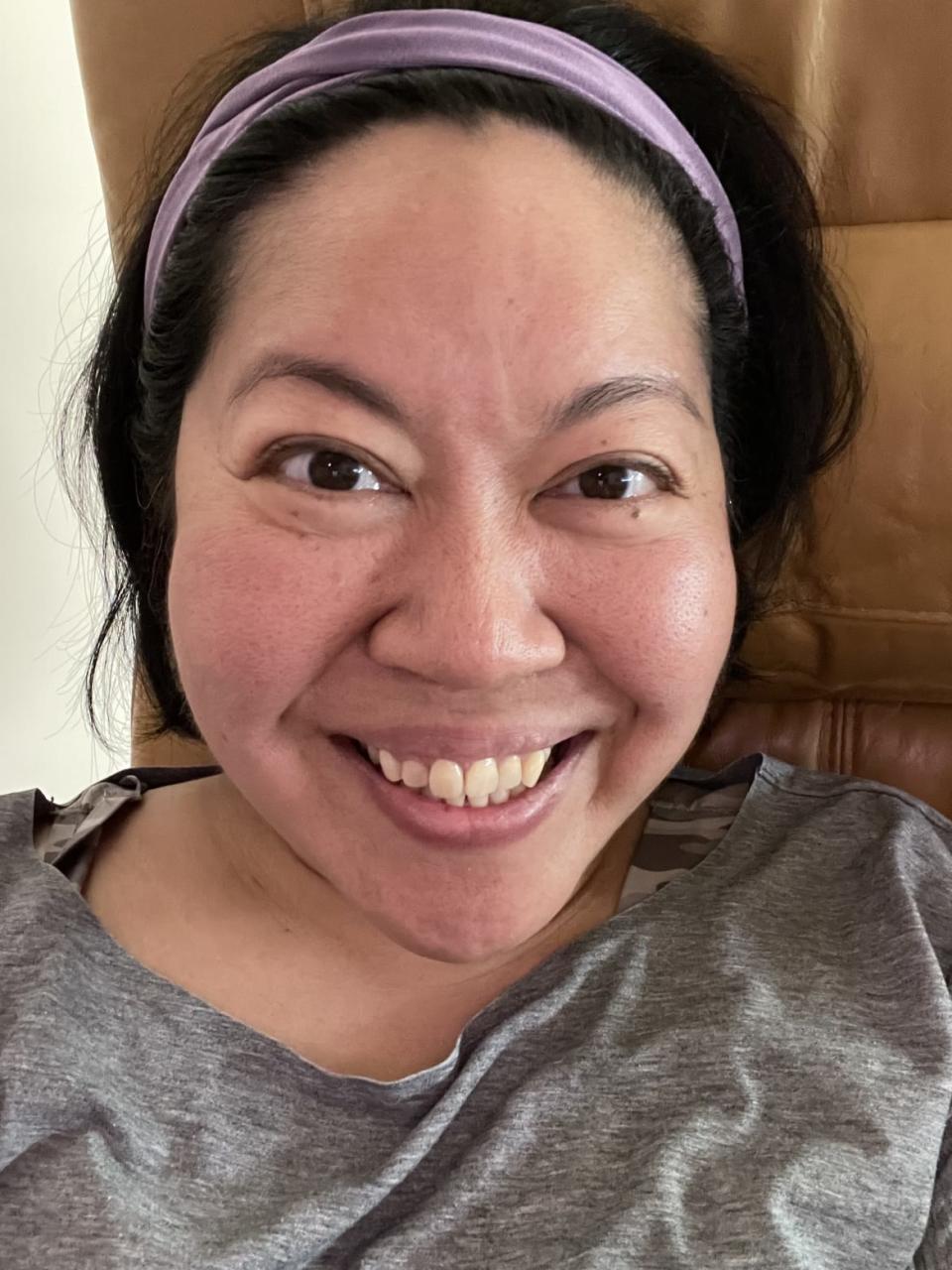

When talking to her, you wouldn’t know that Mio Yokoi is likely going to die soon.

She looks healthy for 47. She’s vibrant, friendly, and talkative. She doesn’t seem to have a problem sharing her feelings about things and exudes an energy that welcomes you into her world while giving you a safe space to open up too. It’s a skill that she’s developed and honed over the course of her career as a psychotherapist. Now, it’s turned into something more: a kind of essential life preserver she’s clinging on to in order to make it through the future.

In September 2020, Yokoi learned that she has stage 4 pancreatic cancer. So, unlike the rest of us who can live our day-to-day lives assuming death is far down the road, she knows that she will die soon. For her, the clock is winding down and there’s only so much she can do about it—so it can be a surprise to find that she’s able to talk about it so candidly.

“When you find out that you have pancreatic cancer, there isn’t anything in that where you go, ‘Oh, I’m feeling hopeful,’” she told The Daily Beast with a laugh. “So I didn’t really want to hear about other people’s experiences because it’s often either not particularly hopeful or helpful. So, for a long time, I was just really shut off. But I also needed to focus on myself and my own mental health.”

Mio Yokoi wants to find a sense of “okayness” with dying from her psilocybin-assisted therapy.

When she received her diagnosis, Yokoi realized that she needed “a new operating system” for life. Before, she—like so many of us—took life for granted. She figured death and dying was something that would eventually happen, yes, but it would happen far down the line. Not when she’s in her forties and just a little more than a decade into a loving marriage with her husband.

So she did the kind of things you’d probably expect: visiting with her therapist, consulting with palliative care experts, and talking with hospice professionals. While it helped to a certain degree, she knew that she needed a bigger and more radical transformation in order to “rejig” her frame of mind, she said.

“From what I learned through my mental health work, I knew that psychedelics have done a lot of good for different conditions and experiences,” she said. “There’s been a lot of studies that have been done for psychedelics and specifically psilocybin for end of life.”

While psilocybin—more commonly known as magic mushrooms—is a controlled substance in Canada where she lives, the government announced in January that doctors would be able to request access to substances such as psilocybin and MDMA in order to treat those with life-threatening conditions.

As luck would have it, where she was being treated at Princess Margaret Cancer Center received funding to start a psilocybin for end-of-life treatment program. However, the wheels of bureaucracy grind slowly and Yokoi had to wait to see if she could get treated. When you’re dying, though, you don’t have the luxury of waiting. Every second matters. Each moment she wasn’t getting the help she needed was time feeling more dreadful and more anxious about what was to come—which isn’t exactly how she wants to spend the last days of her life.

That’s when she found out about a startup called Field Trip that offered psychedelic assisted therapy in her hometown of Toronto. The company was able to gain approval to start treating patients with psilocybin earlier this year as part of the government program.

So that’s how Yokoi wound up being the very first patient in Canada to be treated with psilocybin-assisted therapy for end-of-life anxiety. “I was super excited because I’ll get to experience this after all,” she said.

While research has shown that psychedelic-assisted therapy using drugs like MDMA, psilocybin, LSD, and ketamine can be incredibly beneficial in treating alcohol use disorder, treatment resistant depression, and PTSD, researchers aren’t exactly sure why it works. The brain is still, by and large, a mystery to science. However, researchers have some inkling.

“You can look at it from a whole bunch of different perspectives for how it works,” Michael Verbora, the medical director of Field Trip, told The Daily Beast. He explained that psychedelics encourage two things that are beneficial for mental health: neurogenesis, which is the formation of new brain cells; and neuroplasticity, which is the formation of neural connections in your brain.

Verbora, who is helping guide Yokoi through her psychedelic assisted therapy, likens the human brain to a snow globe. When you take psychedelics, the snow globe gets shaken and the snowflakes fall in different places. When that happens, “that means you get new experiences in life,” he said. This encourages the user to consider completely different perspectives that they might not have otherwise considered.

“With psychedelics, you’re getting a holiday from your ordinary thoughts,” he said. “What that does is your brain realizes, ‘Oh, wait a minute, I actually don’t suffer as much when I take a break. How do I take more breaks from this? How can I start taking breaks from my pain and suffering naturally?’”

Dr. Michael Verbora the medical director of Field Trip, at the psychedelic therapy clinic in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, on Aug. 28, 2020.

Research bears this out. In one study from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, psilocybin assisted therapy was found to be effective in treating depression in patients for up to a year. Findings from a separate trial suggested that the drug is better at fighting depression than commonly prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which often come with a host of negative side effects like nausea, exhaustion, and loss of sex drive.

Despite the fact that psychedelics have been extensively studied and shown to have an incredible impact on treating mental health issues, the biggest hurdle to rolling them out and treating more people is, as you probably guessed, government regulation. These are laws that prevent doctors from being able to help their patients with debilitating depression and anxiety, stopping people like Yokoi from being able to enjoy their everyday life—with what time they have left.

Until the psilocybin approval from the Canadian government, Field Trip has primarily focused on ketamine-assisted therapy to treat those with depression, anxiety, and PTSD. But Verbora knows that there are a lot of people who could benefit from psilocybin—which he said has a host of other benefits that ketamine can’t quite achieve—that won’t be able to due to the stigma and archaic laws surrounding these drugs.

“People on the other end who are approving drug access never meet the patient and don’t know their story,” Verbora said. “I’m not a big fan of bureaucracy interfering between the doctor-patient relationship. That’s my bias.”

Yokoi isn’t a stranger to psychedelics herself. She’s actually done magic mushrooms before when she was in her twenties after spending some time at a friend’s cottage. “It was a hero dose,” she laughed, referring to a particularly large dose of psilocybin that she took. While fun, the thing that stuck with her about the experience is a unique sense of “okayness” with the world that she encountered.

“It was a calm feeling within myself,” she explained. “Just a sense of things are okay. The world is okay. Things will be okay.”

Right now, things for Yokoi are not OK. She’s staring down the barrel of eternity and there’s so much that she’s afraid of. It’s that okayness, then, that she wants to get out of the psilocybin-assisted therapy with Field Trip.

“The okayness that I had is something I think is actually like a big theme of mine because I often don’t feel OK within myself,” she said. “I’m constantly wondering, ‘Did I make the right decisions? Am I a good person? Did I do enough? Have I been good enough to the people that I love and the people that I care about?’”

However, the biggest thing that Yokoi’s worried about when it comes to dying isn’t death itself (though that is something she’s scared of too). It’s her husband. When they got married, they hadn’t thought to apply for life insurance. After all, they were both self-employed. They didn’t have kids. So there wasn’t a lot of reason to get life insurance.

That all changed, of course, when she received her diagnosis.

“That was one of the things that I cried really hard about,” said Yokoi. “It wasn’t even so much that I was going to not be around. It was like, ‘I didn’t do enough for us. I didn’t do enough for you, my husband.’”

She added, “The anxiety really spurred me on to try to get a psychedelic-assisted experience because I don’t want to feel like this failure in life for whatever time I have left.”

It’s with okayness and anxiety in mind that she went into her first psilocybin-assisted therapy session with Verbora at Field Trip's office in Toronto in August. The experience is not entirely unlike what you might find at a typical therapy session. First, she went into a comfortable room and was given the opportunity to lie down. Then she was given a weighted blanket, eye shades, and headphones. She also listened to music (she and Verbora settled on a Spotify playlist called “Music for Mushrooms”).

A woman demonstrates what a patient would experience in a therapy room at Field Trip, a psychedelic therapy clinic in as medical director Dr. Michael Verbora waits by her side in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, on Aug. 28, 2020.

Verbora gave her a 25mg tablet of synthetic psilocybin and sat in the room with her acting as one part psychotherapist and one part trip sitter. And then the two waited.

“I felt like it took forever to kick in,” Yokoi recalled. “I kept thinking, ‘It’s not going to work. It’s taking too long. I’m wasting everybody’s time.’ But apparently it took just 15 minutes to kick in.”

Yokoi began to move around and vocalize her feelings to Verbora. At one point, she began to cry as she felt herself struggling to let go of an undefinable sense in her body. Then it felt like all her “nerves lit up,” she said. “It was almost like there were little beings on my body saying that I needed to start moving.”

It was at that point that a surprising and ironic occurrence happened in her trip: She was able to connect to her body—a body that was dying and actively killing her—in a way that she hadn’t been able to before.

‘Magic Mushrooms’ Fight Depression Better Than Normal Medication, Study Suggests

“It was a really, really amazing experience,” Verbora recalled. “She had so much wisdom and insights and she really invited me to connect with her, which was really nice from my perspective. We did some body work as well, some yoga and some movement. She was really feeling the medicine in her body as well and she hadn’t felt so connected to her body for such a long time.”

After the trip, Yokoi and Verbora had an integrative therapy session where they talked about what she was feeling and what she went through. Later, she said that she was still tired even days after being dosed. However, she walked away from the experience with “a lot to work on,” but also with much more grounding in her sense of self and her health than she ever would have otherwise, she said.

And perhaps that’s the real benefit of psychedelic assisted therapy—and psychedelics in general. It has the ability to pull us out of our typical thought processes—all the stress and anxiety of everyday life—and shake up the proverbial snow globe. You begin to realize that the things that you’ve been afraid of, whether it be your depression or anxiety or your very own body, are so temporary that it’s nothing to be afraid of at all.

“These medicines ground you and allow you to live in the present moment,” Verbora said. “Everybody should try to live in the present moment, but especially if you have a limited amount of time left to be able to give full mind, body, and spirit to family and loved ones.”

Verbora hopes that a paradigm shift occurs with mental health. After all, he and Yokoi are battling against the twin stigmas of psychedelic drug use and talking about death. These are areas that make people uncomfortable. It makes people nervous. It makes them want to shut down and avoid the topics entirely. But it doesn’t have to be this way. Psychedelic therapy can show that when Mio Yokoi dies—and when you die too—there’s a way we can embrace and celebrate it the way we do birth and life.

Death doesn’t have to be a painful, dark, and lonely place. It can be a beautiful trip instead.

Got a tip? Send it to The Daily Beast here

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.