As members of Congress head for the exits, loosely regulated gravy train beckons

The road from Capitol Hill to K Street is designed to have a speed bump.

By law, members of Congress and their senior staffers are supposed to have a one- to two-year cooling-off period in which they refrain from lobbying their former colleagues.

But nearly 120 former members and senior staffers since 2015 have been the sole lobbyist or part of a lobbying team targeting their former chamber during their cooling-off periods, according to a McClatchy analysis of post-employment restriction data from the House and Senate as well as lobbying registration data.

That doesn’t necessarily mean they broke the law.

Those rules are limited in terms of what they specifically prohibit former members and staffers from doing. They ban direct contact with current members or staffers, but do not ban providing behind-the-scenes advice to other lobbyists on who they should contact and what they should say — essentially using a cutout. Former staffers from the House of Representatives are only restricted from lobbying their former office or committee. Lobbying other branches of government isn’t prohibited. And the system effectively operates on the honor system.

The lobbying rules, designed to prevent former lawmakers from immediately profiting from their political connections, are more important than ever as Washington sees a strikingly rapid exodus of elected officials, some of them weary of the toxic partisanship and eager to cash in on more lucrative opportunities.

Violating the cooling-off period is punishable by up to five years in prison and a fine of up to $50,000, but lobbyists who break the law are unlikely to be detected. While the House and the Senate are responsible for flagging potential lobbying violations, both the offices of the House clerk and the secretary of the Senate confirmed to McClatchy that neither regularly checks whether lobbyists have violated the cooling-off period.

The Government Accountability Office annually audits a random sampling of lobbying forms for compliance with lobbying rules, but told McClatchy it doesn’t check for compliance with the cooling-off period. And while the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Washington D.C. is responsible for bringing charges against potential violators, the office couldn’t recall any recent instances in which it actually did.

When presented with McClatchy’s findings, former Wisconsin Democratic Sen. Russ Feingold, best known for his work with former Sen. John McCain on a 2002 campaign finance law, said Congress should revisit the lobbying laws, which were last updated in 2007.

“At a minimum, Congress should insist that the clerk of the House and the secretary of the Senate review lobbying registrations to determine if former members and staff may be violating the law and refer potential violations to the U.S. Attorney’s Office for investigation and prosecution,” Feingold said. “We included tougher revolving-door restrictions in the 2007 lobbying reform package but without enforcement that law doesn’t mean much.”

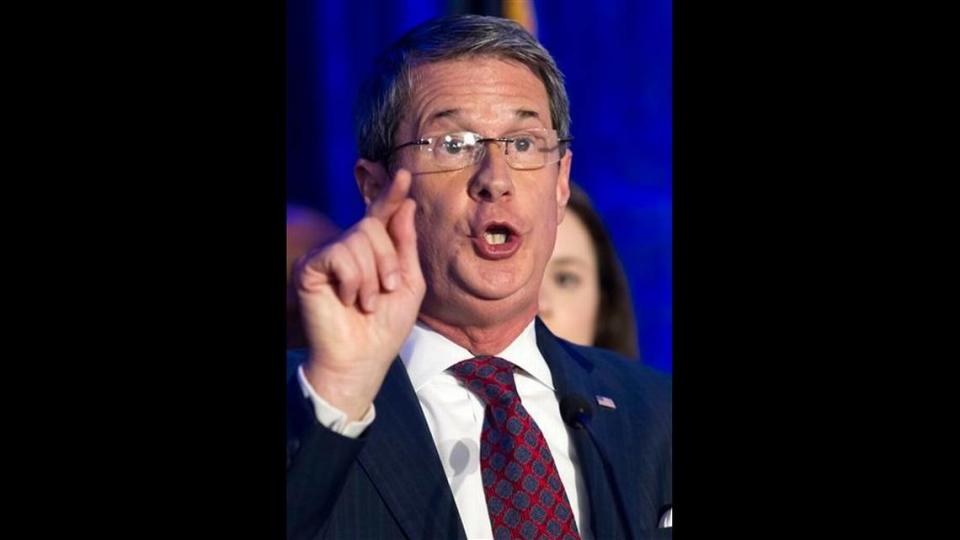

McClatchy’s analysis flagged three former members of Congress — Louisiana Sen. David Vitter, California Rep. Howard “Buck” McKeon, and Florida Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen — whose lobbying forms indicated they had either directly lobbied their former chamber during their cooling-off period or been part of a team targeting their former chamber.

All three are Republicans, and more than 70 percent of the former members and staffers identified in the analysis were from Republican offices.

Republicans controlled both chambers of Congress for much of the period in the analysis and more than 10 percent of the Republican staffers on the list worked for the Republican leadership in one of the two chambers.

But the analysis flagged former staffers from both ends of the ideological spectrum, with aides to several Democrats on the list, including Bernie Sanders’ former chief of staff, Michaeleen Crowell.

And McClatchy’s analysis doesn’t take into account so-called shadow lobbying, whereby former members of Congress and top aides provide many of the same services as a lobbyist but below the legal threshold of activity that would require them to register.

“You’re looking at the tip of the iceberg,” said Meredith McGehee, executive director of the group Issue One, which seeks to reduce the role of money in politics. “You’re looking at the people who bothered to register.”

Mining former connections on the Hill

The 2007 update of the lobbying laws came in the wake of the lobbying scandal that sent super lobbyist Jack Abramoff and former Congressman Bob Ney, R-Ohio, to prison for their roles in a scheme in which Abramoff and other lobbyists defrauded Native American tribes seeking gaming licenses and lavished expensive gifts and campaign donations on Ney and other politicians in exchange for political favors.

The law banned gifts from lobbyists to members of Congress or their staff — and increased the penalty for violating the lobbying rules to as much as a $200,000 fine or five years in prison.

But it left the cooling-off period largely unchanged. When the Senate tried to extend the cooling-off period to two years for members of the House and Senate, the House balked at adopting the same two-year cooling-off period Senators face.

Extending the cooling-off period has historically been met with resistance because many in Congress see it as an unfair imposition, McGehee said.

She was involved in a previous rewrite of the lobbying laws in 1995 as a lobbyist at the government watchdog group Common Cause.

“I have a very vivid recollection of sitting down with a chief of staff of a House member and getting reamed because I was going to deprive this chief of staff from the ability to make a living after leaving Congress,” McGehee said.

The current rules didn’t limit two former members of the House from playing a role in lobbying work that targeted their former chamber during their first year out of office.

Ros-Lehtinen, who left office in 2018, inked a deal to represent a former political supporter from the Miami area, Oscar Cerna, who has been involved in a 15-year dispute with the government of Honduras, which he said drove his Honduran cement company out of business. Ros-Lehtinen, a former chair of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, had been among Cerna’s staunchest supporters in Congress, writing a 2007 letter to then-Honduran President Jose Manuel Zelaya pressing Cerna’s case.

Cerna, for his part, contributed $14,500 to committees supporting Ros-Lehtinen over the past two decades. So it was perhaps not surprising that Cerna turned to Ros-Lehtinen to continue to press his case as a lobbyist. When she retired in 2018, his company Cermar Investments LLC, hired Ros-Lehtinen and another lobbyist at the firm Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld, which she joined soon after leaving Congress.

Cerna’s company has so far paid $30,000 to Akin Gump and Ros-Lehtinen is one of a team of two lobbyists who have together targeted the House, Senate, State Department and Executive Office of the President on Cermar’s behalf. The forms don’t indicate which bodies, if any, Ros-Lehtinen lobbied herself and former members are not prohibited from lobbying other branches during their cooling-off period.

Ros-Lehtinen, a monthly columnist for the Miami Herald, declined through a spokesperson to comment directly. A spokesperson for Akin Gump issued the following statement in response to questions directed at Ros-Lehtinen and other Akin Gump lobbyists identified in McClatchy’s analysis: “The firm is fully aware of and abides by all relevant ethical requirements in its lobbying activities, including post-employment lobbying restrictions of former members and senior staff.”

McKeon, the former chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, also represented a client he had prior dealings with during his time in Congress.

In the wake of the September 2013 shooting at the Washington D.C. Navy Yard, McKeon pushed for the public release of an internal Pentagon report that found security flaws in a system used by the Navy to give contractors and other short-term personnel temporary access to military sites and called for the Navy to stop using the system.

The system hadn’t been responsible for giving access to the Navy Yard shooter, but McKeon nevertheless called for the critical report’s public release.

“The report details critical flaws in the practice of contracting access control for military installations to non-governmental personnel,” McKeon said in a statement. “I believe it to be relevant to physical security on military installations.”

Despite the report, the company managed to keep its contracts with the Navy and it hired McKeon’s newly formed lobbying firm two years later after McKeon left office.

McKeon said a form that indicated he had lobbied the House of Representatives on the company’s behalf in 2015 was a mistake and that he had limited his lobbying work to the Pentagon. He said his lobbying firm would be submitting an amended form.

“I know that there are people from both the House and Senate that try to skirt the issue,” McKeon told McClatchy. “I purposely registered early on so that we wouldn’t do that.”

Former Louisiana Sen. Vitter also told McClatchy that two forms filed in 2017 indicating that he had lobbied House and Senate directly on behalf of a Texas public entity, the Chambers County Improvement District No. 1, had been filed in error.

“I appreciate your pointing them out,” Vitter said by e-mail. “They are incorrect, and I have directed our compliance staff to correct them immediately.”

No one had previously pointed out to either Vitter or McKeon that the incorrect forms seemed to show them doing work impermissible during the cooling-off period.

And no one flagged another report McClatchy found that appeared to show that one staffer had signed his first lobbying clients while still on a congressional payroll. James Peterson’s name appeared on lobbying registration forms dated to 2015 — while he was still a legislative assistant to Democatic Sen. Dianne Feinstein — to represent the California cities of Huron and Riverbank. Peterson told McClatchy the foms had been filed in error by the lobbying firm he worked for after leaving Feinstein’s office in early 2016, Townsend Public Affairs.

“I had no idea they had been submitted,” Peterson said.

Anatomy of a lobbying campaign

The current lobbying rules provide ample leeway for former members of Congress or staffers to be involved in the lobbying process without violating the cooling-off period restrictions. The rules ban direct contact with current members of Congress and their staffs, but do not ban providing strategic advice on who to contact or even what to say. And the rules apply only to contact with congressional offices, not the White House or federal agencies.

“The very purpose of revolving-door restrictions is to prevent former members and staffers from profiting on their inside connections for influence-peddling on behalf of paying clients,” said Craig Holman, the lobbyist for Public Citizen, a consumer advocacy group that seeks to limit corporate influence on public policy. “Yet lobby they do, as full partners of the lobby team, organizing and strategizing the lobbying campaign for whoever pays them.”

Vitter’s lobbying on behalf of the Texas public entity provides a window into the lobbying work that a former member can do during the cooling-off period while staying on the right side of the law.

McClatchy obtained documents through a Texas public records request that show the efforts of his team at the lobbying firm Mercury Public Affairs to help the Chambers County district win a grant from the TIGER program, a multi-billion dollar competitive transportation grant originally launched as part of the Obama administration’s economic stimulus plan. The program attracted notice when one of the projects it financed, the Florida International University bridge, collapsed while under construction, killing six on March 15, 2018.

The Texas project, led by William F. Scott, a major Republican donor who had given $25,000 several years earlier to a pro-Vitter super PAC, decided to hire Vitter’s team in October 2017.

Vitter’s first suggestion was that they target Texas Rep. Brian Babin, a Republican on the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee.

“I know Brian pretty well,” Vitter wrote. “And he’s on the DOT oversight committee — an ideal U.S. House member to get fired up in support and help corral and lead nearby colleagues.”

Vitter’s team then spent months reaching out to congressional offices and federal agencies ahead of a D.C. trip they organized for Scott and his team in early 2018. The itinerary included meetings with Republican Texas Sens. John Cornyn and Ted Cruz, several members of the House — including Babin — as well as the White House, the Department of Transportation and Energy Secretary Rick Perry.

Vitter made clear to McClatchy that he himself did not reach out to congressional offices directly during his cooling-off period.

“I very carefully followed Senate rules by not having any contact with congressional offices on lobbying matters for two years following my service in the Senate,” Vitter said. “For those two years, the congressional part of Mercury’s Chambers County Improvement District No. 1 work was handled by others in the firm.”

Vitter did directly lobby the Department of Transportation and its secretary, Elaine Chao, which is not prohibited by the law. He and his team met with senior officials at the department who told them “pretty directly that U.S. senators calling in meant a lot to the secretary [whose husband is Senate majority leader],” Vitter wrote to his clients.

He instructed his clients to redouble their efforts at winning Cornyn’s support and told them exactly what to ask for from the Texas senator and how to ask for it.

Vitter also picked up the phone and called Chao directly to sell the project.

“After several minutes of small talk regarding my family and New Orleans, which she pursued, I outlined the strengths of the application very thoroughly,” Vitter wrote.

Vitter’s help wasn’t enough for the project win a grant in 2018, but earlier this year, Vitter told his clients that he was already hard at work trying to help them find federal money and would no longer be encumbered by any restrictions.

“[N]ow that my two-year cooling-off period has ended ... I can lobby members directly,” Vitter wrote.

A spin through the revolving door

The last rewrite of the lobbying laws left largely unchanged the restrictions on former top staffers —staffers who make at least 75 percent of what a member of Congress is paid, which is currently $174,000.

The rules ban former top Senate staffers from lobbying the Senate for a year, while they ban former House staffers from lobbying either the member they worked for or the committee they worked on for the same one-year period, depending on their role.

It’s common for lobbyists to work as part of a team and the forms don’t require members of the team to specify which office they targeted. That can make it challenging to determine whether a former member or staffer has actually violated his or her cooling-off restrictions.

McClatchy found one former senior Senate staffer, Christopher Kearney, who went out of his way to specify on his form that he had not lobbied the Senate during his cooling-off period, but his form is the exception.

“The firm and I felt that it was important out of an abundance of caution to make it crystal clear that I did not lobby the Senate,” Kearney said.

McClatchy’s analysis identified more than 100 former senior staffers who gave no such indication on their lobbying forms.

That includes a former top aide to Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, Brendan Dunn, who, at Akin Gump, has been part of several lobbying teams that targeted the Senate for a number of blue-chip clients, including tobacco company Altria, CVS, and Qualcomm. Dunn, whose company bio touts his experience advising Republican leadership on retirement matters, was the sole lobbyist for the American Council of Life Insurers, lobbying the House on a retirement savings bill that had been introduced in the Senate while he was still working for McConnell. A spokesman at Dunn’s firm told McClatchy that Dunn had fully complied with the cooling-off rules.

The analysis also tabbed a staffer-turned-lobbyist who has already taken another spin through the revolving door. Bill Cooper, the current general counsel at the Department of Energy, previously lobbied the House in 2017 and 2018 on Puerto Rico electricity issues for Scotiabank, one of the top lenders to the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority, as well as the North American affiliate of the French natural gas company ENGIE, which owns a large stake in a Puerto Rican energy company. That lobbying came soon after he left his post at the House Natural Resources Committee.

Cooper’s filings didn’t indicate which committees or offices in the House he lobbied, and the lobbying work didn’t come up in his Senate confirmation hearings for his current position at the Energy Department. A spokesperson for the department said Cooper complied with all relevant rules and regulations. As general counsel for the department, Cooper is charged with overseeing the agency’s compliance with ethics rules.

The analysis also flagged former staffers from the other end of the political spectrum, including Michaeleen Crowell, the former chief of staff to Vermont Sen. and Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders. Crowell was part of teams at the firm S-3 Group that lobbied the Senate on behalf of 11 clients, including the Sinclair Broadcast Group, Boeing, Duke Energy and the Internet Association, a trade group for major tech companies such as Google, Amazon and Facebook. Crowell’s lobbying teams brought in more than $1 million for their lobbying work during her first year out of the Senate.

Crowell told McClatchy that she would be amending the forms to make clear that she herself had not lobbied the Senate during her cooling-off period.

“I never lobbied the Senate during the ban at all,” Crowell said. “I was very serious about not even having the appearance of an improper contact.”

Of course, if it were up to her former boss, Crowell wouldn’t be lobbying at all. Sanders has said that if elected president he would institute a lifetime lobbying ban for former members of Congress and their senior staffers.

Shirsho Dasgupta contributed to this report.