A memorial for the forgotten dead

In a small patch of woods, just a block from downtown Stapleton, next to a little field of purple and yellow wildflowers, rest the remains of at least 37 people, graves that until last month, have been mostly unmarked for generations.

Among the dead are eight members of the Stapleton family, including Col. James Stapleton, the man the city was named for.

Dr. Fay Stapleton Burnett said that she learned of the family graveyard several years ago while reading her great grandfather, Col. Stapleton’s, journal. The diary gives a day-to-day account of the final three years of his life, from 1885 to 1888.

Burnett said the family knew that the primary monuments had been moved from the family cemetery to Stapleton Baptist’s around 1968.

“The cemetery was being vandalized,” she said. “People were breaking markers and taking urns and they decided to move the big obelisks over to the church. There was no way to move the remains. In this soil, it would have been a wooden casket and the remains and bones would just be dust. So they decided not to dig up the dust.”

But after reading the journal, Burnett learned that there were more than just those who had been listed on the obelisks who had been interred there.

“He wrote about it,” Burnett said. “He talked about going to ‘plank up’ the graveyard. That means fix the fence. The first grave here was his little son Willie. That would have been in 1861. But he also gave the breakdown of how many whites and how many black people were buried here. If it wasn’t for this diary, we wouldn’t know anything else.”

In the diary, Col. Stapleton mentions that the family cemetery was also the final resting place of eight white people and 21 black people.

“We only know the names of the family members,” Burnett said. “These would have been hired hands or sharecroppers. Some of them could have been former slaves, but we know that James (Col. Stapleton) never owned any. This would have been after the Civil War and I guess whoever died on his farm, they buried them there.”

She figures that everyone interred in the cemetery would have died between 1861 and 1868, the year Col. Stapleton died. After that deaths in the area were interred at the then newly built Stapleton Baptist Church.

A few years ago, Burnett went looking, and there, covered in decades of dead leaves, among the tangled vines and lush undergrowth on the site of Col. Stapleton’s farm, she found a worn and broken marble ridge rising above the dirt. Clearing away the topsoil she found an old concrete foundation and the scattered shards of a few broken tombstones.

“I talked it over with other relatives and we didn’t especially like that the bodies were still there and there were no markers remembering any of these people,” Burnett said. “In another generation, I though, nobody will remember them at all.”

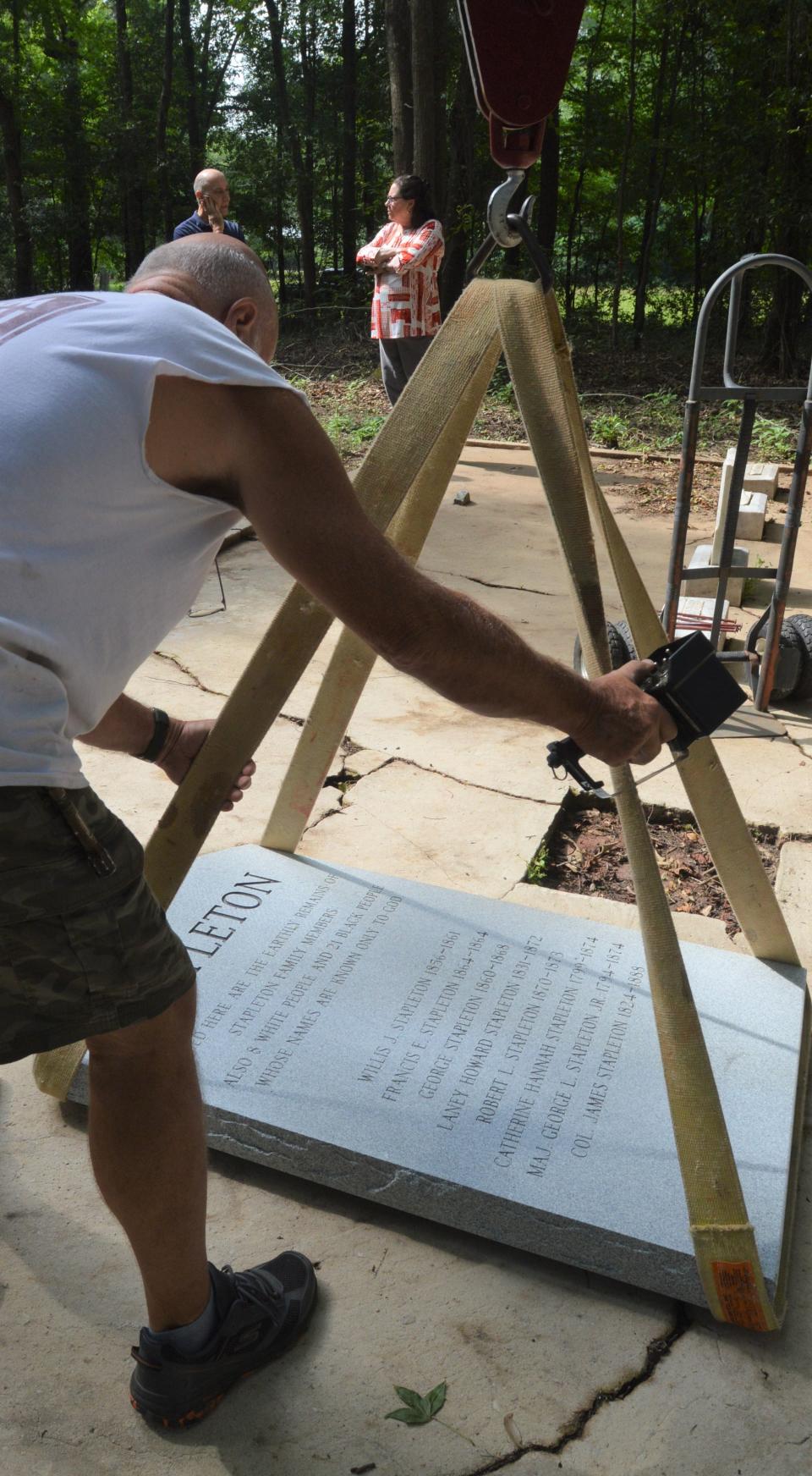

That’s when she started talking to the family and collecting financial support and encouragement from her many cousins. Together they raised the funds and purchased a monument that was raised at the site in June.

In the shaded lot today it reads: “Stapleton: Buried here are the earthly remains of Stapleton Family members: Also eight white people and 21 black people whose names are known only to God.”

Among those known to be buried at the site are: Willis J. Stapleton 1856-1861, Francis E. Stapleton 1864-1864, George Stapleton 1860-1868, Laney Howard Stapleton 1831-1872, Robert L. Stapleton 1870-1873, Catherine Hannah Stapleton 1799-1874, Maj. George L. Stapleton Jr. 1794-1874 and Col. James Stapleton 1824-1888.

Col. Stapleton and his father, together served more than 50 years in the state legislature. Both were Baptist preachers.

“We thought it was important that all of these people have some kind of marker where their bodies lie,” Burnett said. “These other people, their families don’t know where they are buried. There were no funeral homes here back then and they just had to bury them where they could. There probably aren’t even any records. We wanted, at least for our generation, to reclaim it and mark it and hopefully someone else will take an interest and preserve it after us.”

Burnett’s family has lived in the Stapleton area since 1784. She has written two books based at least partly on extensive research that began with researching this family history and plans to one day publish parts of her grandfather’s journal.

This article originally appeared on Augusta Chronicle: A memorial for the forgotten dead