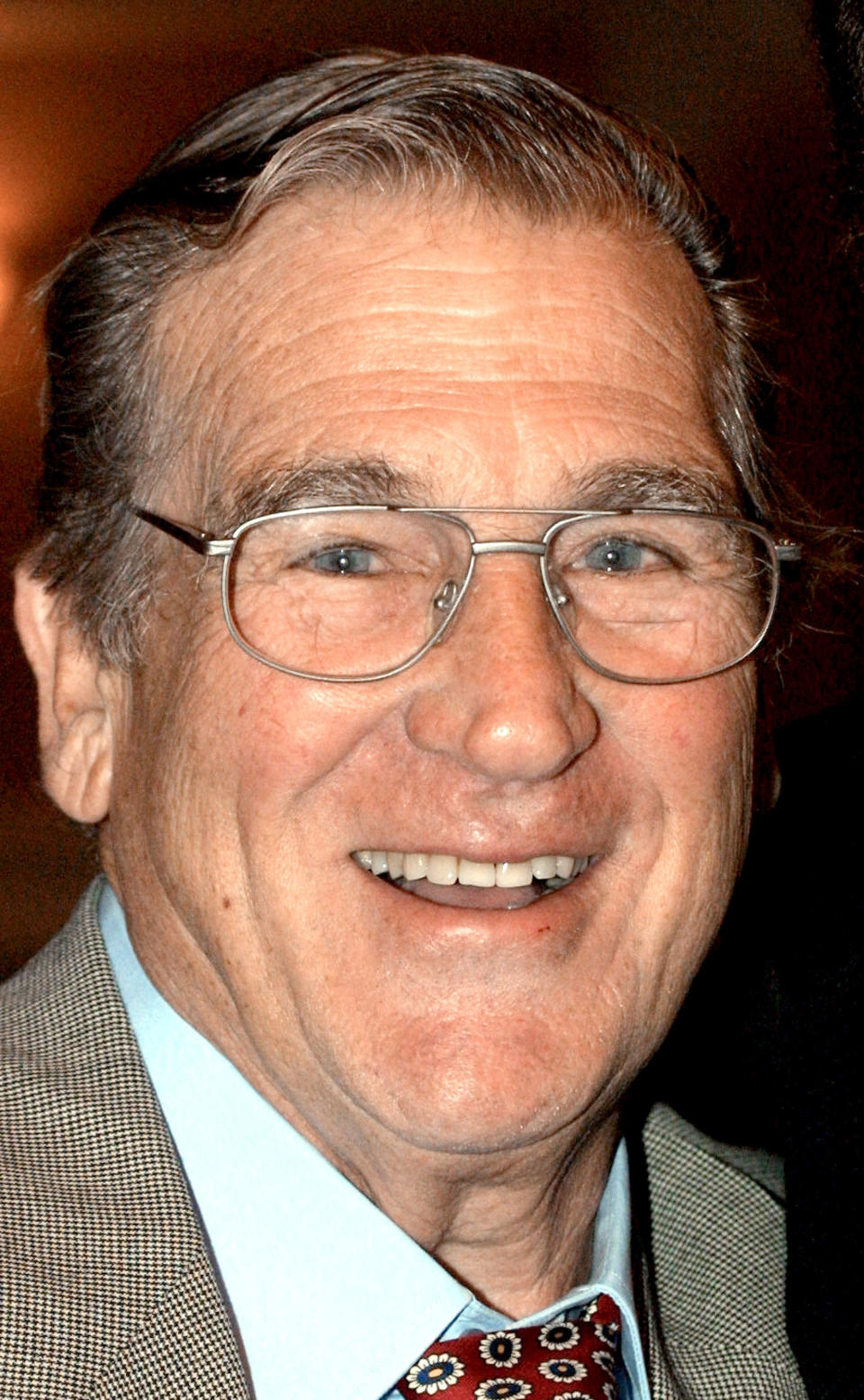

In memoriam: A few final words and a Sinatra story about the Chicago-born comic Shecky Greene

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

CHICAGO — In recent days in the places where older folks gather to remember and talk about what they remember, conversations were peppered with the name Shecky Greene.

Only those of a certain vintage know that name, fewer still can recall seeing him on television and even fewer can share memories of what he said and did on the stages of such bygone places as Mister Kelly’s on Rush Street, Mill Run Playhouse in Niles or various Las Vegas outposts.

These trips back in time were prompted by the recent death of Greene on Dec. 31, 2023. The local newspaper obituaries contained some of the particulars of his career, a few highs and lows, but they mostly failed to focus on the significance of the man. He was of a time that is gone for good.

Greene was one of the last of a generation of stand-up comics who, as Gerald Nachman writes in his entertainingly enlightening 2003 book “Seriously Funny: The Rebel Comedians of the 1950s and 1960s,” “had to get your attention in any way possible … To grab your ear, they needed to make a racket, verbal and visual. Nightclubbers went out to laugh, and few were fussy about who they laughed at.”

It’s a tough life, comedy, even now, described by Nachman as “the world’s most hazardous occupation.”

“It’s tougher than other art forms because there’s no shield to hide behind — no book, no canvas, no camera, no orchestra, no script, no co-stars, no choreographer. It’s just you and your wisecracks; if the act fails, you have failed … The comedian is the whole show, the flesh-and-blood work of art.”

Greene was, in his time, as big a nightclub star as there was. It was he who opened for Elvis in Vegas, who opened the new Mill Run Theater in 1970, and was making as much as $150,000 a week in 1960s Las Vegas.

He had his troubles — once driving his car into the fountain in front of Caesars Palace in Vegas — and drank too much. In later life, he would find that he had some mental ills and with medication was able to settle down. He had some modest success in TV and film and was happily married for nearly four decades to Marie Musso. He played Vegas a bit and Vegas is where he died.

But his roots were firmly here, since 1926 when he was born Fred Sheldon Greenfield and raised on the North Side (Sullivan High School) and throughout his life remained close to many here.

“I have great memories of Shecky,” said Marc Schulman, who is the son of the late Eli Schulman, once a noted restaurateur and the founder of Eli’s Cheesecake Company, of which Marc has long been president. “He and my father were very close, real friends, not just those of the celebrity kind. I’d known him since I was born and can remember the many nights he would share a table with my dad.”

Both were World War II veterans and they shared a deep Jewish heritage. They also shared a passion for the ponies. As Greene put it in an interview, as a young man he “had a silent partner to support — I discovered how to bet the horses.” (The late Chicago business owner and philanthropist Joseph Kellman named one of his race horses for the entertainer.)

Greene and Eli became pals even before 1962, when Schulman opened Eli’s Stage Delicatessen on Oak Street, in the Rush Street nightlife area. It immediately became a hangout for many stars who would drop in for late-night dinners after performing at Mister Kelly’s and other nearby clubs.

Among them were such other people as Woody Allen, Bobby Short and Barbra Streisand, who would drop by for late-night suppers and lively conversation.

It was through Eli that I met Greene, who was also a regular visitor to Schulman’s later restaurant, Eli’s the Place for Steak, located on Chicago Avenue where Lurie Hospital now stands. He was a wildly entertaining conversationalist and storyteller. Often the name Sinatra came up, since he was a pal of Eli’s. Greene had been Sinatra’s opening act in Las Vegas and elsewhere, until their strong personalities clashed and they had a falling out.

Indeed, one of Greene’s most memorable routines involved how “Sinatra saved my life.” It focused on his being beaten in a hotel lobby by five men until Sinatra said, “OK, boys, that’ll be enough.”

Greene insisted the story was true and also had some interesting things to say about a watch Sinatra had given Schulman, who proudly wore it. But sitting with the comic and even seeing his act, it is difficult to capture him in print. His style was almost improvisational, energetic and filled with such treats as impressions, manic physical routines, stories and singing. He seemed so eager to please. As he once put it to a newspaper interviewer, “I’ve never had an act. I make it up as I go along.”

You can get short samples of that on the internet, that oasis of immortality where after life goes, laughs still echo.

“He was one of a kind,” Marc Schulman said. “He was here when my dad died (in 1988). He was very upset and as a gesture of his deep affection for my dad, he asked if he could give me one of his own shirts for Eli to be buried in. And that’s what we did.”

That wonderfully tender gesture meant a lot to Marc and his family, and he kept in touch with Greene by phone over the ensuing decades and by sending him the occasional cheesecake. He now says, “I think they and their friendship represented a sort of sentimentality that seems to have vanished, gone for good.”