Memories of a Staten Island Childhood

It is a rare person who hasn’t experienced the mystic bond between memory and the senses. How, for example, a certain smell can, like a time machine, transport us instantly to a place, and moment, in our past.

Five senses are what we’re meant to have. New York, as it happens, is a city of five boroughs. Having lived in them all, I often am “returned” to each, though none more often than that “forgotten” one.

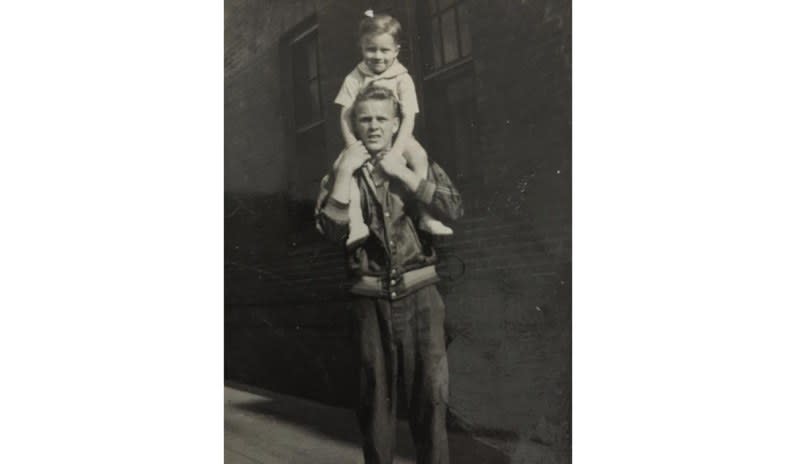

It all began when my grandparents left the Emerald Isle of Éireann to cross the Atlantic in hope of better prospects. Years later, my parents and I set forth from the Bronx, and made our way by ferry to the emerald island of Staten. As my grandparents no doubt did, we stared in windswept awe as the boat passed Lady Liberty. The memories to which our senses connect us may seem random, but actually are pieces of a mosaic we can assemble. And while the picture formed tells a story of its own, it also points, like an icon, to a treasure beyond.

When it comes to that sense of smells, one is pervasive enough to be the olfactory canvas of my youth. Laugh if you want, but it’s bubblegum: attar of schoolyard and street. Not just any kind either, for this, as did so many things, came in a pair of good options. In this case, Bazooka and Double Bubble. A choice was required; a kind of commitment that helped define you: Converse or Keds; Giants or Jets; North Shore or South.

The soundtrack of those years was a familiar mix: the Beatles, Hendrix, the Jackson 5, and lots of gold in between. But there was another, more elemental, backdrop; a blue-collar orchestra of iron and steel, whose music was the clanging hooks of docking ships, the rattling roar of anchor chain, the bells of buoys, gently bobbing, on dark green harbor swells.

There was the wheezing of garbage trucks, hydraulic mastodons, prompted forward by tooth-whistle to the next group of cans. Sometimes that whistle came from where we hid, causing the truck to advance, and a crewman to dump half the can onto the street. For some reason, they never seemed to find that as hilarious as we did.

There were referee whistles, that trilled the frozen air of Travis Field, and hothouse hoops at Port Richmond‘s C.Y.O. Sirens of every kind, at every hour, that held the day together like wire round the bales of The Advance, tossed from trucks, then delivered from yellow sacks slung grimy across our shoulders.

From our home in Tompkinsville, you looked diagonally right and saw the Verrazano; left, and your eyes filled with the Oz of the Manhattan skyline. A quick bounce up Victory Boulevard, and you came to Clove Lakes Park, whose stone boathouse, and trees, like maidens bent to their reflection at water’s edge, seemed a Constable painting come to life.

Two images from those parks still transport me: the hexagonal paving stones, uniform throughout the city, from Central Park to Prospect, from Van Cortland to our own Tappen Park; across from Stapleton Library, a sanctuary (in the shadow of the projects), where I fell in love with reading. The other is the image of the single leaf, outlined in white on a field of green. An emblem of Robert Moses’ stealth empire, it suggests Many leaves, one tree, and links each park to every other in the City of New York.

Nothing, however, returns me more fully, or directly, to the heart of Staten Island than the brilliant melancholy of the foghorn — especially while running, when with earnest mantras rising in frost-clouds from your lips, you notice dusk’s curtain reach the floor, the last streetlight flickered on, and still you were not home.

Long days, long nights; afternoons of solitude, unbuffered by virtuality, admitted the wonder and dread that sculpt the young soul on its way. Childhood, after all, is a time of yearning. And the engine of all yearning is hope. As you lay in bed, staring at the dark ceiling, it was hope that, like an unseen tide, drew you toward the unopened gift of morning.

Not all kids knew gentle nights. For them, there was a riptide, or whirlpool, churning in numbing chaos, almost always of a family somehow broken. Some of us made fun of eccentricities that were, in fact, symptoms of a suffering we could not see, and they powerless to share. There’s no greater regret than what those cheap laughs may have cost the kids at whose expense they were made.

Through the erupting colors of autumn, the sobering sharpness of winter, and the teasing of spring breezes, I longed for school to end. After a week of summer vacation, I started to count, impatiently, the days till school began again. I missed those kids, who today are stored among what’s most precious in the vault of memory.

I missed the nuns who taught us too, who incited in me love of the saints, especially the martyrs; heroes, who, like the glamorous figures high above the Thanksgiving parade, were upheld here by the labor-seasoned hands of women who walked the walk of Christian life, the Halifax Sisters of Charity.

I played basketball at Good Counsel, football at Farrell, and was blessed to make friends at both, the friendships thriving unto this day. Staten Island has imprinted itself on me. Deeply. And deep is my gratitude for grandparents and parents who made it possible. Grateful to all there then, who I visit now whenever a scent or sound pulls up and says, “Hop in!”

I’m at a point where options, though bright, have narrowed, and days are measured in Prufrock’s coffee spoons. At night, when staring at the ceiling, I focus more on the prospect of a different morning. And the foghorn, when I hear it, reveals itself for what it’s always really been, a trumpet from beyond the world; an exhortation of mutuality — in the Psalmist’s words, “deep” calling out “to deep.” As the voices of that antiphon merge, so too the pieces of this life’s mosaic, illumined by hope blossomed, at last, in an unimaginable dawning.