Memory loss, gnarled fingers, panic attacks: COVID-19 didn't kill these Americans, but many might never be the same

An avid skier will lose eight of his fingers and three toes due to complications from the coronavirus. A 27-year-old who beat the virus is plagued by panic attacks and depression. A Florida survivor struggles with memory and vision loss.

Deaths by COVID-19, the disease brought on by the coronavirus, has garnered much of the nation’s attention, especially as U.S. fatalities surpassed 100,000 this week. But many of the more than 1.7 million Americans who've contracted the disease are confronting puzzling, lingering symptoms, including aches, anxiety attacks, night sweats, rapid heartbeats, breathing problems and loss of smell or taste. Many are living a life unrecognizable from the one they had before.

USA TODAY interviewed more than a dozen COVID-19 survivors to capture their thoughts on beating the virus that has infected more than 5.8 million people worldwide and learn how their lives have changed. Here are their stories.

At home with tubes in his nose

Lately, Angel Andujar, 73, can’t walk from his bedroom to his living room without getting winded. Tubes in his nose feed oxygen to lungs recently ravaged by COVID-19.

Andujar spent 18 days in a Clifton, New Jersey, hospital, struggling to survive after catching the coronavirus. Initially, recovery at home was tough. He would sleep only a few hours a night before waking up, gasping for air. He stayed away from the MSNBC broadcasts he once watched regularly because too much COVID-19 coverage made him anxious.

Andujar, a retired respiratory therapist originally from Puerto Rico, is used to keeping busy: working on projects around the house, cutting the grass, visiting his grandchildren. All those have been put on hold.

He doesn’t know if he’ll have long-term lung damage. For now, he’s enjoying being surrounded by friends and family. Earlier this month, he watched through a bedroom window as his grandson Miguel celebrated his fourth birthday in his yard. A neighbor, a retired fireman, parked a fire truck on the street and ran the siren, to Miguel’s delight.

“As long as I have my daughter and grandkids, I don’t need anything else,” he says. “That’s enough for me.”

Her friends are dying from COVID-19 as she recovers

Two months after she relocated to Denver, Ravi Turman thought her nagging cough was residual altitude sickness or a bad cold.

She checked into a hospital emergency room on March 22, where she collapsed into a coma and spent 10 days on a ventilator, wrecked with COVID-19.

After she returned home, Turman, 51, constantly asked herself why she had recovered when so many other African Americans are contracting and dying of the mysterious disease. Recent reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that black Americans are being hospitalized and dying from COVID-19 at disproportionately higher rates than whites.

Turman’s Facebook site is filled with reports of friends and families across the U.S. dying from the disease. In one family she knew from Indianapolis, all seven members contracted COVID-19 and three of them died.

She still struggles with back pain but feels she’ll be back at 100% soon. She wants to show African Americans and other minority groups they can survive COVID-19, too.

“It isn’t necessarily a death sentence,” she says. “You can beat it. Don’t give up hope.”

She survived 9/11, now her heart races from coronavirus

At her darkest moment, when her lungs squeezed closed and she felt near death, Wendy Lanski latched on to one thought: “Osama bin Laden didn’t kill me. I’m not dying from this virus.”

Lanski, 49, a 9/11 survivor, spent 13 days in a New Jersey hospital battling the coronavirus. Her fever spiked to 103 degrees, she had bad chills and it felt like “something was sitting on my chest,” she says. Doctors debated putting her on a ventilator but decided to keep her on oxygen instead. She slowly recovered.

Now back home, Lanski worries if the rapid heartbeat and fatigue that followed her home are permanent.

It's not her first tragic event. She was sitting at her desk on the 29th floor of the North Tower of the World Trade Center when the first plane crashed into her building on Sept. 11, 2001. She scrambled down the stairs and into the street, just as the second plane hit.

The initial fog of confusion surrounding those attacks – Who did it? Where is it safe? – feels a lot like the uncertainty circling the coronavirus, Lanski says.

“Sometimes I think I’m destined to live through tragedies,” she says.

For now, she wears a heart monitor to keep track of her rapid heartbeat. She often wakes up in the middle of the night in cold sweats.

“The fear of the unknown, that’s really the worst part," she says.

Her father gave her coronavirus; he died while she was sick

Tracey Alvino thought things were looking up when she finally brought home her dad from a Long Island, New York, nursing home in March, where he was rehabbing from neck surgery. She didn’t know Daniel Alvino, 76, was riddled with the coronavirus.

The virus spread through her home like a brushfire, infecting Tracey Alvino, as well as her mother, brother and boyfriend. Two days later, Daniel Alvino became so sick he had to be rushed to a hospital.

Tracey Alvino battled the virus from home. She got a high fever and lost her sense of taste and smell. Pain in a foot she fractured years ago suddenly flared up. Her armpit glands hurt, too.

The toughest part was when a doctor asked if she wanted to take her dad off his ventilator. The hospital staff said there was nothing more they could do for him. As she suffered from the same virus that was killing him, Tracey Alvino made the decision to let her father go. He died four days later.

It took 17 days to cremate Daniel Alvino and another month to inter him because of the backlog of bodies. Earlier this month a few limited family members gathered at St. Charles/Resurrection Cemeteries in Long Island to finally lay her father’s remains to rest.

'This has just crippled me with fear'

Jacki Palmer is no longer gasping for breath with chest pains. Instead, the 27-year-old Houston resident faces a new host of challenges: crying fits, insomnia and depression that some days makes it hard to get out of bed.

Palmer spent four days in a hospital in March after contracting the coronavirus while on a cruise to Mexico with family members. She remembers how nurses dressed head to toe in protective gear to bring her medication, how alien and terrified it made her feel.

After returning home, it took about 10 days for the back pain and fatigue to fade but TV reports of patients dying alone in hospital rooms sent her into depression and questions whirled through her head incessantly: Why did she survive? When will she start feeling normal again? What if the dark moods never go away?

“It’s a constant, anxious spiral in my head,” Palmer says.

She started seeing a counselor online and joined a support group on Facebook. Donating plasma also helped brighten her mood, though she could only donate once a month due to her weakened condition.

Palmer's anxiety is never too far off. Recently, while at the supermarket, she saw a woman without a face mask picking out a potato. It sent her heart racing.

“I was losing my mind,” she says.

Palmer, an IT auditor, says people should realize the battle against COVID-19 doesn’t end when survivors leave the hospital.

“I’m a very strong, independent young woman and this has just crippled me with fear,” she says.

'It’s like a dragon waiting to eat you alive'

For 11 days, Patricia Cruz Elostta laid in a bed at a field hospital set up in New York's Central Park to treat coronavirus patients. Cold air snuck into the tents spread across the field and thunderstorms shook the air around her. At times, she could hear other patients gasping for air and dying.

“Shortness of breath, weakness, desperation,” Cruz, 57, says, recalling her experience at the makeshift hospital. “Your spirit was just broken down.”

Her condition eventually improved enough to be transferred to a nursing home for rehab. There, she met up with her mom, Maria Alvarado, 80, who was also recovering from COVID-19. One day, as they sat together at a table, Cruz watched as Alvarado seized up and collapsed on the floor from a heart attack.

Alvarado survived and mother and daughter returned to their Astoria, New York, home to continue recovery. These days, Cruz, an occupational therapist originally from Colombia, is trying to get strong enough to return to work, while taking care of her mother, who mostly stays in her bedroom.

When she goes for walks outside, Cruz takes frequent breaks, stopping on benches to catch her breath. She’s starting to cook meals and clean her home, tasks she cherished pre-pandemic. But constant sharp pains in her back and right hand remind her the virus is not done with her yet.

“It’s like a dragon waiting to eat you alive,” she says of the virus. “It will take everything it can from you.”

She came home from the hospital, then she had a pulmonary embolism

Lucretia Sette Morrone spent seven days in a Long Island, New York, hospital with chills and fever, battling the coronavirus. When doctors sent her home, she knew she wasn’t well – just better than the crush of sicker patients streaming into the hospital.

At home, she had a fever for 30 straight days, quarantined to her bedroom as her husband left meals at her door and cared for their adult autistic son. She was starting to feel better when one day she suddenly had trouble catching her breath. She returned to the hospital, where doctors found a pulmonary embolism. Five more days in isolation.

"It’s never-ending,” she says.

Since returning home, her body and legs still ache. Last week, she took a walk with her husband and had to come straight home for a nap. She hopes the symptoms will one day vanish, but she’s not sure they will.

It frustrates Morrone when people only talk about those who have died from COVID-19 or those who have fully recovered.

“There’s a whole bunch of people in between who are suffering and fighting it still,” she says.

His toes and fingers will likely have to be amputated

Gregg Garfield uses a walker to steady his balance. The top halves of his fingers are black and gnarled and will soon be removed, a constant reminder of the 31 days spent on a ventilator fighting for his life against COVID-19.

Garfield, 54, was “Patient Zero” at Providence Saint Joseph Medical Center in Burbank, California, outside Los Angeles. He caught the coronavirus while on a ski trip with friends in Italy in February and was admitted to the hospital on March 5, becoming its first COVID-19 patient.

During his 64-day hospital stay, Garfield’s lungs collapsed four times, his kidneys failed and infections flared throughout his body. Doctors gave him a 1% chance of survival. His hands and feet became so oxygen-starved while on the ventilator that doctors will soon amputate eight of his fingers and three toes on his right foot.

Despite the setbacks, Garfield, who owns a credit card processing company, says he’s lucky to be alive and surrounded by supportive friends and family. His days now consist of early morning stretches followed by physical therapy – wall squats, exercise bike – three days a week. One of his top goals: get back on the ski slopes.

“Today is really the only day you can count on. Tomorrow may not be here,” he says.

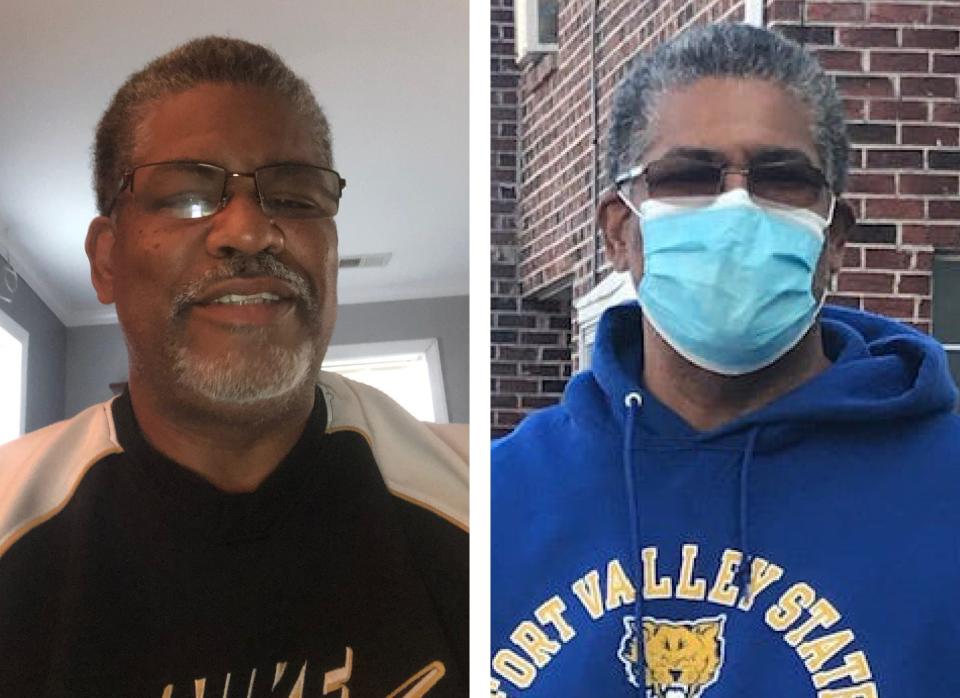

Shots of morphine for the pain

Curtis Jefferson thought he was recovering from coronavirus when he felt a sharp, severe pain in his left side.

This was a new symptom. He had endured a fever, dry cough, headache, no sense of taste. None of those had forced him to the emergency room, but this one did.

The diagnosis: along with contracting COVID-19, he now had pneumonia. He’d have to stay in the coronavirus ward for six days, getting shots of morphine for the pain and swallowing antibiotics to fight pneumonia.

“I knew I wasn’t dying,” he says, “but it was such an ordeal.”

In the hospital, he saw “only a few nurses, a couple doctors, and they were covered head to toe. They didn’t come near me unless they had to.”

Afterward, Jefferson quarantined in his basement, away from his wife and three teenage children, watching “Law & Order” reruns and westerns. He slept fitfully at night. Climbing the stairs to reach the bathroom left him gasping for breath for five minutes.

Now “99%” recovered and back to work in Washington, D.C., as an electric construction mechanic, Jefferson, 58, still isn’t sure how or where he got the virus.

“I walk around my neighborhood and see people with no masks, talking in each other’s faces,” he says. “People are going back to beaches in certain states, and rates are going up. What are we doing? This is crazy to me.”

Back to work at a nursing home after coronavirus

Cliff Roperez hugged his 7-year-old daughter for the first time in almost six weeks. She snuggled into him and started to cry.

“Daddy,” she said, “now we can play again!”

A few weeks earlier during her birthday party, Roperez couldn’t celebrate with her or play hide-and-seek. After testing positive for coronavirus on March 30, Roperez and his wife agreed he’d quarantine himself in their bedroom in a tent.

A nurse at an elderly care facility outside San Jose, California, Roperez, 47, was exposed early despite wearing an N95 mask as soon as the virus was confirmed in the U.S. At one point, he and his wife worried he would die. He reviewed his life insurance policy.

He recovered, he says, following “Asian therapy:” His wife made tinolang manok, a Filipino chicken soup, and ginger tea with honey. Three times a day, he’d inhale steam from a basin of salted, boiling water.

After quarantining himself for 12 days, Roperez returned to work, where COVID-positive employees had their own entrance. His energy sapped, he’d tire easily. But in a facility with 120-plus elderly patients terrified of the virus, he’s trying to lift spirits. He makes his personal protective equipment into costumes – astronaut one day, superhero the next – “and it gives light to everybody,” he says.

He tested negative for coronavirus on May 11. Santa Clara County, where he lives, requires two negative tests before residents can declare themselves coronavirus-free. He’s waiting for results from his second test.

She's afraid of getting coronavirus again

Margaret “Margie” Waldrum had a panic attack at the grocery store. It was the first time she had to wear a mask and she didn’t want to touch the cart. She was scared she might get the coronavirus again.

For nearly two months, Waldrum, 68, battled the virus, including a 10-day stay at Valley Hospital in New Jersey with double pneumonia.

But life after COVID-19 has also been hard. She’s 18 pounds lighter. She’s still winded, still fatigued. Her rheumatoid arthritis feels worse than ever so that she can’t turn the cap on a water bottle, can’t grip a steering wheel. A recent walk lasted about six minutes before she felt unbearable pain in her feet and knees.

“I’m 68 years old, but I wasn’t like this before,’’ she says.

She’s anxious about her future. Will the virus invade her body again? Should she get psychotherapy? Will she be able to return to work as a receptionist at the front desk of an assisted living facility?

In the days ahead, she has a chest X-Ray and a scan planned to check her lungs.

"It's going to take a little longer for me to jump back," she says. "You can’t give up."

Someone 'really, really big was sitting on my chest'

Mary Pflum Peterson’s four children didn’t like it when their mother was sick with coronavirus, cordoned off in her bedroom and unable to play with them. But now that she's recovering, they like it that mommy can’t raise her voice to scold them because even the slightest exertion leaves her breathless.

“You know I can’t yell, but you know you’re really in trouble!” she says when they act up.

Pflum Peterson, a 47-year-old writer living in New York City, tested positive for coronavirus on March 21. She’s not sure how she contracted it or from whom. Even if you’re young, healthy and in good shape, she says, the virus “shows you who’s boss.”

She used to run 2 to 5 miles a day in Central Park. Now she’s winded after walking up four flights of stairs to the front door of her Manhattan home. Long walks outside, she says, can “cloak me in exhaustion.”

The worst of her symptoms – complete loss of taste and smell, burning lungs and the sense that someone “really, really big was sitting on my chest” – have passed. But the weariness lingers. She’s traded daily runs for daily naps.

Her 13-year-old son is still sick with coronavirus, fighting off high fevers and crippling headaches. He’s the only other person in their family to test positive. She knows firsthand he won’t be back to normal anytime soon.

“A lot of us want to snap back,” she says. “And you have this realization that the virus is going to be here for a while.”

'Nobody wants to be near you'

Susan Owens sat in a hospital waiting room enclosed by a see-through divider and reserved for those who had tested positive for coronavirus. The people on the other side of the wall stared and avoided her gaze. She felt branded. Overwhelmed, she started to cry.

“I understand, I do, but it’s hard,” she says. “I guess it’s just because people are so scared.”

Owens, a 55-year-old banker, lives in the small community of Moultrie, Georgia, about an hour north of Tallahassee, Florida. She tested positive on March 30, followed by three consecutive days of fevers of 101 degrees and shortness of breath so extreme “it felt like an elephant was sitting on my chest and squeezing my windpipe.”

Since then, she has tested positive for antibodies. But she keeps testing positive for the virus, too. And because her job requires a negative test before she can go back, she hasn’t been to work since March 27.

At night, her legs burn like they’ve been scorched by the sun. She quickly loses breath while planting flowers outside.

But the stigma stings the most.

“Nobody wants to be near you,” she says sadly.

Her fourth time in the hospital

In her hospital room in Fairfax, Virginia, Donna M. Talla keeps the television on CNN to track the death toll and learn more about hydroxychloroquine.

She suspects the medicine used to treat her COVID-19 weeks earlier may have saddled her with side effects, including a racing heart that landed her in the hospital on Monday for the fourth time since March.

“It’s been a hell of a ride,’’ she says. “It’s the roller coaster you get on and you just want to get off it.”

Talla tested positive twice for COVID-19. She suspects she picked up the virus while grocery shopping in March. She had a backache, then a rash, then headaches. Later came fevers and chills. After she struggled to climb the stairs, she went to the emergency room.

Later, news of blood clots on her lungs ‘'almost broke me...But I bounced back.’’

As her health improved, she returned to working from home as a director of sales for a media company.

She tested negative – twice. She posted on a Facebook page for survivors, borrowing quotes from "Rocky" and encouraging others to fight.

Then she was back in the hospital, this time with concerns about her heart.

“There are people who are dying in this hospital,” she says. “I’m one of the lucky ones and I don’t take that for granted for a minute.”

On Thursday, she went home from the hospital – again.

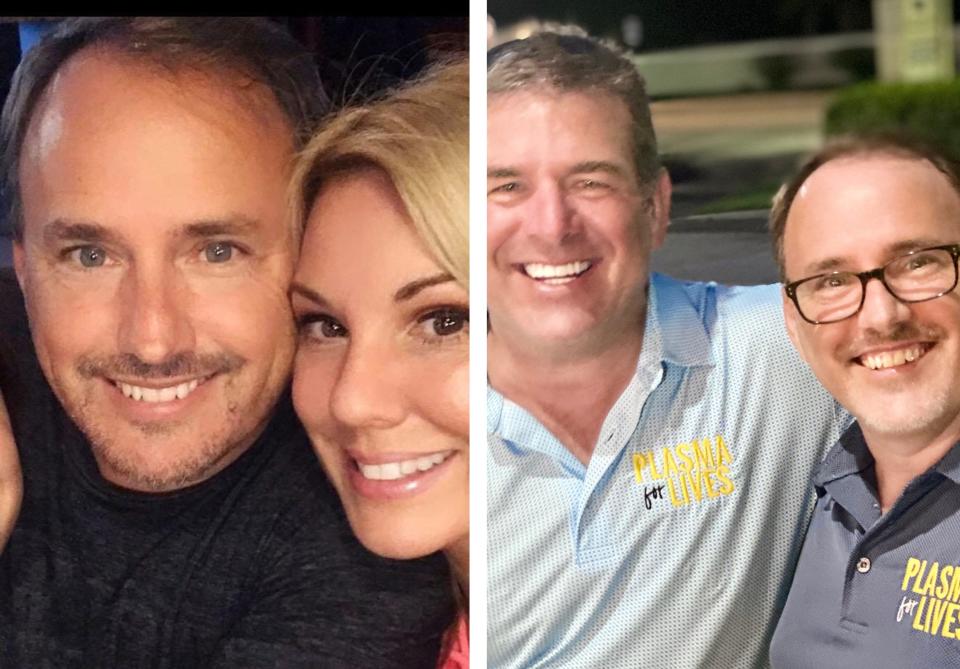

The Easter miracle

His wife called it an “Easter miracle.” After eight days in a medically-induced coma, Kevin Rathel awoke in his hospital bed that Sunday, April 12, tears trickling down his face as he saw his wife and three children talking to him on an iPad.

Five days later, lines of doctors and nurses cheered him on as he left the Orlando Regional Medical Center in Florida, where he received the plasma injections he credits with beating COVID-19.

But for Rathel, 52, the agony was just starting.

He’s trying to regain the 25 pounds he lost. Before COVID, he routinely walked four miles a day. Now? A quarter-mile, maybe a half, because he tires so easily. He wakes up from night sweats and quietly covers his side of the bed with a towel so his wife can keep sleeping.

“Poor girl, she spent a month trying to save my life,” he says.

He can’t see like he used to, can’t retain information. When he grasps for a memory or a name, he screams: “COVID brain!”

During a recent group Bible reading, Rathel squinted to see the words on the page. He dragged his finger under each word. And, after memorizing the books of the Bible as a child, he now struggles to list the four gospels.

“John, Luke…,” he says. “I can’t remember.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Coronavirus survivors battle ongoing symptoms, might never be the same