Memphis woman learned chilling truth about how her ancestor illegally enslaved Black men

In 2018, a friend of Carla Peacher-Ryan recommended a book. The friend had seen a reference to a sheriff’s deputy named Paul Peacher who was accused of enslaving Black men in the 1930s in eastern Arkansas. Since Peacher is not a very common name, the friend wondered if they were related.

At first, Peacher-Ryan winced. An enslaver in her family? She had known her ancestors to be poor folks who held racist ideas. But she had always thought they weren’t in a position to actively enslave people – especially in the 1930s. Slavery had been outlawed for seven decades by then. But her curiosity got the best of her and she went online.

After a few clicks on Ancestry.com where she had already begun building out her family tree, six words flashed across her screen: Paul Peacher is your great uncle.

“And I just couldn’t believe it, you know, but then I knew it was true,” said Peacher-Ryan, now a retired Memphis attorney.

Further research led her to a second connection.

She learned from family members that her step-grandmother had once been married to a man – a rural Arkansas judge – who had aided Peacher in his enslavement scheme. The revelation hit her hard.

Her step-grandmother, Mary Mitchell, had once given her an engagement ring – a huge, sparkling four-carat diamond that Peacher-Ryan proudly wore on her finger for 26 years. But now, from what she was hearing, that ring had sealed her step-grandmother’s marriage to a man who had wrongfully sentenced Black men to work on Peacher’s land without pay.

“I don’t know how other people are, but a lot of family stories I hear, I’m like, ‘Mmmmm. Really?’ ’’ Peacher-Ryan said with an uneasy, skeptical laugh. “(But) once I put all those together, I was like this ring and this story are connected. I don’t know how, but I feel like there’s a connection here.”

That connection and her deepening curiosity would take her back to Earle, a small farming community on the broad and fertile Delta of Eastern Arkansas and introduce her to descendants of the men Peacher was accused of enslaving. It would teach her how forced labor, especially on farms, endured long after the U.S. outlawed slavery. And, as she would learn, what happened in Earle, Arkansas, in the late 1930s had put her ancestors at the center of national media attention that spotlighted the plight of abused farmworkers, a struggle for dignity and living wages that continues to this day.

Another view: Tigerbelles Coach Ed Temple's lessons on life and sports can help you prepare for 2024

An interracial labor union spurred planters to push back hard

In 1936, the Great Depression was in full swing. Cotton prices had dropped dramatically, creating an economic crisis that exacerbated already tense relationships between farmers and agricultural workers.

One former sharecropper, George Stith, spoke to PBS as part of a 1993 documentary series about the Great Depression.

“Sharecroppers had no voice,” he said. “The boss told you how much cotton you made, how much money you owed, and how much you got, if any.”

Dismal working conditions in the Earle area led 11 white and seven Black farmworkers to form an interracial labor organization in 1934 that became known as the Southern Tenant Farmers Union. Membership quickly rose to the thousands.

In the spring of 1936, the union called a strike. Between 2,000 and 5,000 workers left the fields demanding 10-hour workdays and $1.50 per day, which is equal to about $34 today – still a long way from a living wage, but almost double what they had been getting.

That same day, landowners generally known as “the planters,” gathered in Earle, Arkansas to figure out what to do. Paul Peacher spoke up.

“If you stand by me, I’ll break up this strike,” Peacher told them. He promptly arrested more than a dozen Black men for vagrancy. All were either on their way to work or at their houses. That didn’t matter. Given Peacher’s violent reputation, the men complied.

One of the men arrested was Winfield Anderson, 51, who was married with two young kids. He’d been deemed “totally and permanently disabled” by a doctor after hurting his arm in a tree-cutting accident the year before and was making $10 a week in worker’s compensation.

Another man, 22-year-old John Curtis, was on his way to a farm job when Peacher stopped him. “Get in this car,” he said. “I am going to take you up to the county farm and put chains around your goddam legs.”

The next day, Peacher brought eight of the men to Judge T.S. Mitchell – the man who had once been married to Peacher-Ryan’s step-grandmother – who was also the mayor of Earle. The Black men had no legal representation. Within minutes, the judge fined them each $25, or about $560 today, and sentenced them to 30 days’ labor.

They would be forced to clear timber on property leased by the very man who had arrested them: Paul Peacher.

Descendants of enslaved men visit the land their ancestors toiled in

Last summer, the Institute for Public Service Reporting and the Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change organized a trip back to Earle with Lekendrick Bunting and Marquette Smith, two descendants of the Black men enslaved on Peacher’s land, along with Peacher-Ryan.

Nine decades after Anderson and Curtis were sentenced to work the land, it’s still farmland as far as the eye can see.

Earle’s population – just under 2,000 people — is about the same as it was then.

While standing in the same field their ancestors stood, Smith and Bunting imagined what it might have been like to be taken from their families into forced labor.

“I empathize with him,’’ said Smith, a Memphis financial relationship manager who is a descendant of John Curtis. “I just, I get the feeling that myself, like, man, just to feel hopeless and desperate.”

“He just told him to get in the car. My family doesn’t even know where I’m going,” said Bunting, 28. “… Just to even think about that. I don’t know where I’m going. Don’t know how long I’m gonna be gone. They don’t know.”

A guilty verdict for the enslaver seemed up in the air because of racism

Word soon got to the Southern Tenant Farmers Union about the enslaved men. A preacher named Sherwood Eddy snuck onto the land to talk to the men. He immediately returned to Memphis and contacted a friend from college who also happened to be the Attorney General of the United States, Homer Cummings.

A federal investigation followed, and the men were released. But would anyone be held accountable?

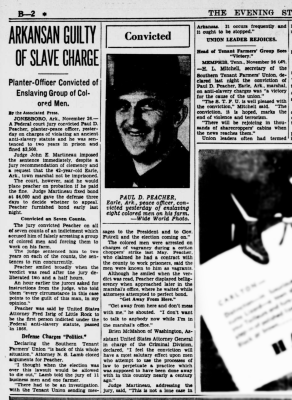

The federal government indicted Peacher that September under a rarely used anti-slavery law. The town’s planters raised money for his defense. The eight Black men, including Anderson and Curtis, testified. Peacher told a reporter he was confident the all-white jury would find him innocent.

Robert Thompson, a Paragould, Arkansas attorney who wrote his college thesis on Peacher in the 1990s, said Peacher had good reason not to worry.

“If you look at the history of civil rights legislation up into the ’50s and ’60s, it was just sort of taken as a given that white people will not convict anyone for violating the civil rights of Black people,” Thompson said.

At first, the jury couldn’t reach a verdict.

Judge John Martineau scoffed at the jury in open court: “Every circumstance points to the guilt of this man. This is not a lone case in Arkansas. It ought to be stopped.”

On a second attempt, the jury found Peacher guilty, but recommended no jail time. He was fined $3,500, or about $79,000 today, stripped of his title, and served two years of probation.

For Peacher-Ryan, her great-uncle’s punishment was not justice.

For her, the diamond ring she’d worn so proudly all those years – the one her step-grandmother gave her – had lost its shine. She sold it for $15,000 in 2022 and gave the proceeds to the Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change at the University of Memphis.

“To me the ring had become a symbol of racial terror and social injustice,” she said.

Peacher’s conviction and the national attention that came with it brought a wave of embarrassment and shame across Arkansas in 1936, said Thompson.

“If you shine a light on something that nobody wants to see, you sort of force change. And that’s what happened in this case,” he said. “The Arkansas legislature pretty quickly began outlawing debt peonage.”

The union’s impact also would be felt for decades, said Michael K. Honey, a labor and civil rights historian. Stories of its interracial organizing influenced the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement.

They “remembered that there was a time even in the Ku Klux Klan districts where Black and white people in agriculture areas got together and joined together to change things for the better,” Honey said. “So, that gave people hope that even in Mississippi or eastern Arkansas in the ‘60s, it might be possible to have a movement.”

Editor’s note: Lekendrick Bunting faces a second-degree murder charge in connection with a 2019 incident. Prosecutors say he shot and killed a 17-year-old girl while firing at a carjacking suspect. He’s pleaded not guilty. The case is ongoing.

This article is a condensed version of a story originally published by the Institute for Public Service Reporting at the University of Memphis as part of its Civil Wrongs project investigating historical racial injustice. To read the full version and listen to the podcast, visit psrmemphis.org and click the Civil Wrongs tab.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Black men were illegally enslaved by the ancestor of Memphis retiree