Mental Health Awareness Month: Palm Desert man heals after decades of trauma

The minute you step foot inside Daniel Marquez's Palm Desert home, you get a sense of who he is. Before you've spoken a single word to him.

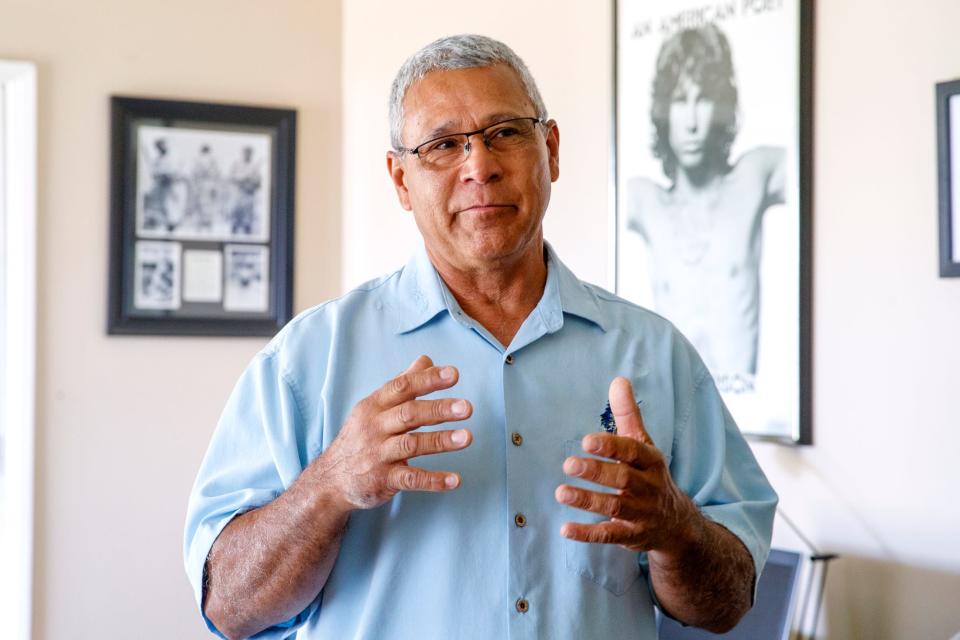

Black and white photos of The Doors singer Jim Morrison, boxer Muhammad Ali, English rock band The Beatles and Los Angeles Dodgers players line his living room wall. Based on this choice of imagery, it's easy to guess that Marquez, 62, loves rock 'n' roll and America's favorite pastime.

But each of these icons also holds a deeper significance for Marquez, which you discover once he recounts his life's journey — or as he says, the "many lifetimes I've lived in this short lifetime." As a young child, Marquez was sexually abused, but he was told to never speak about it. That trauma, along with witnessing abusive behavior from his father, who later died by suicide, impacted Marquez's life in a number of ways, leading him down his own spiral with alcohol abuse, anger and unstable relationships.

It wasn't until Marquez went to rehabilitation and sought mental health care that his life began to change. Today, Marquez has been sober for more than 20 years, and he's found a way to help others who have gone through similar trauma in their life. The Palm Desert resident shares his story with It Happens to Boys, an organization that helps men who have been sexually abused through their own healing journey.

As a staunch mental health care advocate, and in honor of Mental Health Awareness Month, Marquez sat down with The Desert Sun recently to share his story — with the hopes of encouraging even more people to seek help.

"I feel that I make a difference, and I never felt that before," an emotional Marquez said. "If my experience can make a difference, then I'll do it."

SIGNUP FOR OUR FREE PALM DESERT NEWSLETTER: Get top stories to your inbox once a week.

The fighter

The triumphant photo of heavyweight boxing champion Ali standing over a fallen Sonny Liston during their 1965 match hangs above the desk in Marquez's living room. In many ways, Marquez has been a fighter throughout his own life.

Growing up, his father was a heroin addict and alcoholic who was in and out of Marquez's and his two siblings' lives. He was "not a nice guy," Marquez said, adding that his father used to hurt his wife and children.

When Marquez was 5 years old, he was sexually abused by an older neighbor and a teenager, separately, in his Silver Lake neighborhood. He would walk to school, which was located several miles away, and the abusers would catch him at gas stations or take him behind dumpsters, alley ways and abandoned garages.

"At an early age, I was like a secret agent. I was hypervigilant about what's around me, who's in front of me or behind me," Marquez said. He added that he became really good at running quickly, climbing trees, houses and fences and hiding in small spaces.

"From that time, I was in survival mode for most of my life," he said.

When his father found out about the abuse that his son was experiencing, Marquez recalled that he yelled at him, told him to go inside and never speak about it to anyone.

A few years later, his father — who was 27 at the time — took his own life. Marquez was 8.

"I have father wounds, which most men do have, and women have them, too. When I work with men in the 12 step program, it really revolves around their fathers," Marquez said. "Especially Hispanic men, they don't want to talk about anything. They want the machismo."

"That's just the tradition of what we teach in our society: Be strong and take care of the family, go to war, die for your country, sacrifice yourself," he added. "We don't tell them take care of yourself, take care of your feelings."

That trauma didn't fully register until Marquez had his own children, he said. He never let his children walk to school or play outside on their own. When his son asked him why, Marquez, who began to cry thinking back to his childhood, told his son, "Because I know what's out there, and I don't want that for you"

Following the death of his father, Marquez continued to keep his trauma to himself. Even as a young child, he recognized that his family was struggling, so he "didn't want to add to that." Unfortunately, keeping it inside led to health issues: he wet the bed, developed a stutter and experienced stomach pain that was later diagnosed as an ulcer. No one ever asked him if something was wrong, he said.

Today, he said he's keen on his children always having a voice and expressing their concerns.

His early youth was also filled with violence. The family moved several times while he was in third grade, and as the small, new kid at every school, he was bullied frequently. Marquez said he would black out when bullies would get him to the point of tears, and he would beat up whoever was in front of him. He didn't realize it at the time, but that was a sign of "the wounds from this past" resurfacing. His middle school in Los Angeles was located near five prominent gangs, which were always recruiting new and young members, he said. It was common for Marquez to engage in at least one fight a day.

"That kind of became normal from where I was," he said. "But it's not normal. I know that now."

His mother later remarried, and Marquez found himself in another difficult relationship with a male figure in his life. Though the two bonded over sports, his stepfather was an alcoholic who could not tap into his emotions, and Marquez often felt like he never fully recognized him as a son.

Related: Coachella's Hotel Indigo site may be turned into county drug abuse, mental health facility

'Live fast and die young'

Marquez's teenage and young adult life continued down a dark path.

At 12, he started drinking, and later he started using drugs. Drinking and drug use was a "natural thing" in his family, but "also being emotionally compromised and wounded had certainly something to do with" why he gravitated toward the two, he said.

"It was an inner battle of self worth, and depression had a lot to do with it. I drink and I feel better with myself, so I'm going to continue to drink," Marquez said about that time in his life. "It was a way for me to basically hide from myself."

He also experienced suicidal ideations at the time. He said he couldn't bring himself to take his own life, however, because "it would affect people," so instead he engaged in dangerous activities, such as motocross, off-road racing and skiing. If he died while doing one of those activities, he thought, "I'd be good, it wasn't suicide."

Marquez looked to his framed poster of a shirtless Morrison with the words "An American Poet" printed on it in his Palm Desert home. Morrison was known for his drinking and drug use, and he died unexpectedly at age 27. With the singer and Marquez's own father dying so young, he said he did not plan on living past 27 either.

"I totally identified with this guy here because ... I was going to live my life after him," Marquez said, pointing to the poster. "You can see how destructive I was with myself. Live fast and die young, right?"

Erratic behavior, drug use and ignoring the root of his trauma led to encounters with law enforcement and failed relationships. With his life essentially falling apart, Marquez realized he needed a change, so his family encouraged him to move out to the Coachella Valley when he was 21 years old.

Despite the poor hand life had dealt him up until that point, he still had one goal in mind: to raise a family. Marquez wanted to recreate the family he grew up in and make changes, but he didn't know exactly how to do it.

He married at 26 and had two sons with his first wife. It was "wonderful" to be a father, he said, but he admits he "didn't realize how sick I was still." He was sober during the course of the 3 1/2-year marriage, but he didn't seek help for his trauma or anger issues.

In his second marriage, he had a daughter and two stepsons. The relationship ended, however, after seven years.

Today, Marquez can recognize that he struggles with codependency and control issues. Back then, though, it was a cycle of failed relationships that continued until he sought help.

A home run

The final straw, so to say, came when Marquez entered another marriage that followed a similar path. This time, though, Marquez decided he would prove people wrong, and he decided to enter rehab at 39.

He has been to rehab before, he said, but "it clicks when it clicks."

In the late 1990s, Marquez went to the Betty Ford Center, a private, nonprofit drug and alcohol treatment center in Rancho Mirage, founded by former first lady Betty Ford and former U.S. Ambassador Leonard Firestone, that provides in- and out-patient treatment as well as rehabilitation programs and virtual care.

One day, he attended a presentation on changing the family legacy led by Jerry Moe, then the national director of the Hazelden Betty Ford Children's Program. Moe explained that many people in treatment look to the child within themselves and consider how they have been impacted by addiction. That lecture changed Marquez's life.

"He was talking in that childlike voice and being the kid and it was amazing to me to see a grown man be vulnerable and childlike and not have shame because that is not me," Marquez said. "I was just sitting there in amazement watching him, and I had tears run down my eyes." Thinking back to that moment still evokes the same response in him even after 20-plus years.

"I just had an epiphany and realization that he was talking to my inner child. My wounded child was the one that was crying," Marquez added. "I kind of understood instantly that I was wounded and needed help, and it was time to admit that."

Marquez has been sober since Aug. 16, 1999.

Moe remembers that day as clearly as Marquez does. Standing in front of a 120-person audience, Moe recalled that 80% of the people in the room related to his lecture. Marquez's response, in particular, stood out to him.

"At first it was almost kind of a startled response, and I interpreted it as, 'How does he know this about me?' Then came tears and then there came a vulnerability on his part, but there was also this sense of hope," Moe recalled. "Sometimes you'll see people get vulnerable and the amount of trauma and what they've gone through is so overwhelming that they just sob uncontrollably, but for him, while there were tears, there was also a nodding of the head, 'Yeah, I relate, I get this, somebody just gave me a piece to the puzzle.'"

Since their first meeting, Moe has become the father figure Marquez always needed in his life, he said. More than just being a mentor in his healing journey, the two have bonded over their shared love of baseball.

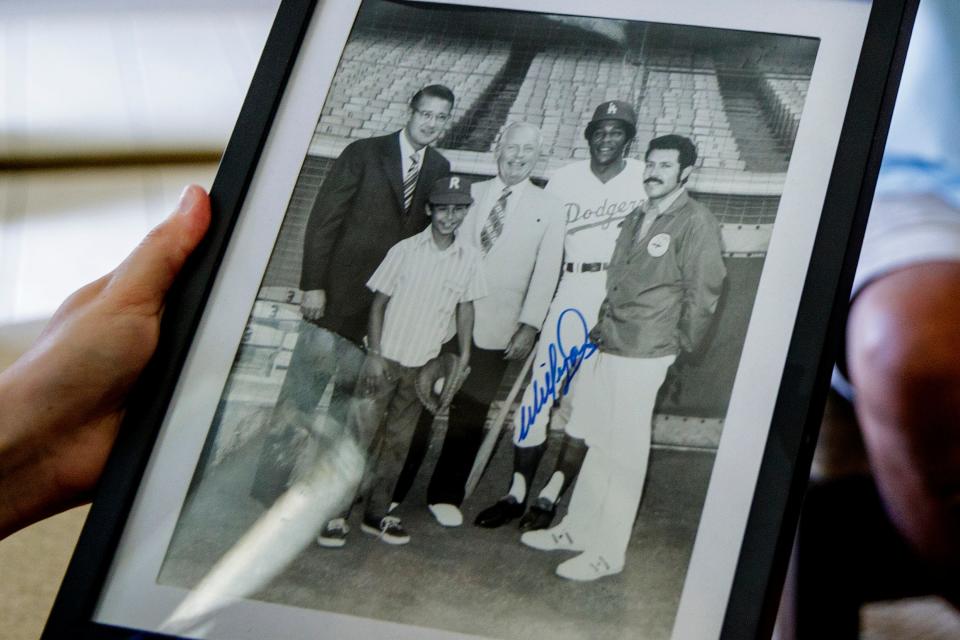

In his home on a recent morning, Marquez proudly showed off a signed photo he took with Los Angeles Dodgers player Willie Davis and his stepfather when he was a young boy. He played baseball at Glendale Community College as a young man, and the 62-year-old desert dweller still has some moves today.

"I'm actually still pretty good at it, I surprise myself," he said.

Marquez later worked at the Betty Ford Center as a maintenance coordinator and played on a co-ed softball team with Moe and other colleagues. Being on the team with his "hero" was a dream, and they even won the league together.

He even gets protective of his father figure. During one game, a player on the other team hit the ball, came around first base and pushed Moe. Marquez recalled that he got in the other player's face and said, "You ain't doing that to anybody, especially him."

"Everybody cleared out, and Jerry comes over and said, 'Don't worry about it, I got this.' Then he looks over at the guy and says, 'Bring it on,'" Marquez said with a laugh.

Into the light of a dark black night

Following his time at the Betty Ford Center, Marquez continued care at the Barbara Sinatra Children's Center, also located in Rancho Mirage, which has programs dedicated to supporting those who have experienced abuse as children. He was also in other group therapy settings and 12 step addiction programs.

Often he was the only man in a room of people who had experienced sexual abuse. Some men would come, but he said they would leave "once they started getting vulnerable." He described his time in those groups as "hard, emotional and wonderful all at once."

"I was the enemy because I'm a man and they were molested by men," he said, "and they were the enemy to me because they're women and women are abusers in my adult life emotionally."

In those settings, he learned how to have nonsexual intimate relationships with women and to communicate more effectively, which later helped him in his own personal relationships.

With all the time he spent working on himself, eventually an opportunity arose that would allow him to give back.

Psychotherapist Carol Teitelbaum, who has lived in the valley since 1993, has worked with men and women who have suffered trauma and abuse in their lives. She realized, however, that there weren't many programs available for men who had been sexually abused,

"Men who do not deal with their sexual abuse and trauma in their early ages end up with a lot of rage, a lot of drug and alcohol use," Teitelbaum said. Keeping that trauma inside can further lead to domestic violence, depression and suicide, she said.

As a result, she founded It Happens to Boys 14 years ago. Teitelbaum holds weekly group sessions with men on Zoom, though they were in-person prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Seeing men open up, be vulnerable with each other and feel that they're in a safe environment to do so can only be described as "the best" feeling for Teitelbaum.

When she was just getting started with the program, she wanted to invite men who had experienced sexual abuse and were on their healing journey speak at various events, and that's when she connected with Marquez.

"Daniel made a huge impression on people because he has experience in a 12 step program and sponsoring," Teitelbaum said. "He's been a great asset to our program."

Marquez also speaks at workshops and schools through It Happens to Boys on a variety of topics, such as bullying and codependency. Talks at schools are the most rewarding, he said, but also the most painful for him because he's reminded of the struggles he faced during those years.

At one presentation at Palm Desert High School, he discussed sexual abuse and the importance of boundaries in a health class with 32 students. Later, students received index cards where they could write down whatever thoughts they had. Out of those 32 students, 14 were being abused or had been abused. The Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network states that one in nine girls and one in 53 boys under the age of 18 experience sexual abuse or assault at the hands of an adult.

It's difficult to see so many children go through a similar experience as him — Marquez began crying at the thought of that day — but the fact that there are children out there who need help shows him how valuable It Happens to Boys is.

"I have a whole bunch of letters from kids, thanking me and telling me what they're doing," Marquez said. In one emotional letter, a student said he told his father what he learned from It Happens to Boys, and the young boy learned that his father was sexually abused when he was younger. That talk between them encouraged the father to get help.

It Happens to Boys also holds an annual conference, which was put on hold due to the pandemic, but will return in March 2023. Up to 250 people attend the conference annually, Teitelbaum said.

Marquez said he is ready to share his story and hear from other healers again. Moe and Teitelbaum typically speak at the conference, and several authors who have written books on abuse and healing have as well, such as John Lee and Dave Pelzer.

"I'm grateful because I know the worth of doing and seeing these presentations with people and what a gift it is to the healing part," Marquez said. "Also for me, knowing what it is in my own journey, I can learn through them how to give it back to other people."

It's been a long road, and though Marquez has experienced significant changes throughout his life, the healing process and work is never quite done. In his current relationship, he has learned to set boundaries and help his partner with her own struggles. His three children, six stepchildren and 13 grandchildren have also been a big part of the journey.

Marquez admits that he still has many unresolved issues with his father, but he focuses on being the father that he wanted in life. He was also able to find closure with his stepfather, who died from Alzheimer's disease last year.

As important as baseball is to Marquez, so, too, is music. He heard The Beatles' 1964 album "Meet the Beatles!" when he was 5, and it marked his introduction to rock 'n' roll with songs such as "I Want to Hold Your Hand" and "This Boy." The tunes were likely most interesting to him as a young child. As he's gotten older, though, music has been a healing element to him, and certain lyrics, such as The Beatles' 1968 classic "Blackbird," have found ways to support him through his journey.

"Blackbird singing in the dead of night/Take these broken wings and learn to fly/All your life/You were only waiting for this moment to arise."

Mental health resources

It Happens to Boys: Visit www.creativechangeconferences.com, or contact Teitelbaum at 760-346-4606 or catbaum@earthlink.net.

It's Up to Us: The site has tools for having conversations, checking in on friends and referrals to places people can go to get immediate help. Visit https://up2riverside.org/

CARES Line, (800) 499-3008: The Community Access, Referral, Evaluation and Support line is answered by licensed clinicians who provide support and crisis intervention, as well as connections to outpatient, inpatient and community resources.

Peer Navigation Line, (888) 768-4968: Not sure where to start? The peer navigation line connects you to someone who is currently recovering from their own mental health issues in Riverside County. They will talk to you about how you're feeling and direct you to resources that could help.

2-1-1 Community Connect: By dialing 2-1-1, Riverside County residents are connected to a local information hotline for individuals in crisis.

National Alliance and Mental Illness, Coachella Valley, (888) 881-6264: Provides support groups (for those experienceing mental illness and the loved ones of those experiencing it) and behavioral health resource referrals to residents from Desert Hot Springs to the Salton Sea.

Riverside County 24/7 mental health urgent care, Palm Springs, (442) 268-7000: If you are experiencing troubling thoughts and need immediate help, the clinic is able to instantly connect you to counseling, nursing and provide psychiatric medication, if needed. Everyone is welcome regardless of insurance or ability to pay for services. The clinic is open 24/7 and no appointment is needed. Located at 2500 N. Palm Canyon Drive, Suite A4, Palm Springs.

Crisis Stabilization Unit in Indio, (760) 863-8600: Individuals experiencing troubling thoughts who need immediate help can go to the clinic at 47-915 Oasis St., Indio.

National Suicide Prevention Hotline, (800) 273-8255: The hotline is available 24/7.

Ema Sasic covers health in the Coachella Valley. Reach her at ema.sasic@desertsun.com or on Twitter @ema_sasic.

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: Mental Health Awareness Month: Palm Desert man heals after traumatic past