This mentally ill man was pepper-sprayed, choked and hooded before dying in state prison

As Marcus Penman slammed his head against a cell door while suffering a mental health episode, not one Kentucky state prison guard tried calming him down. And no mental health care provider was called to deescalate the crisis.

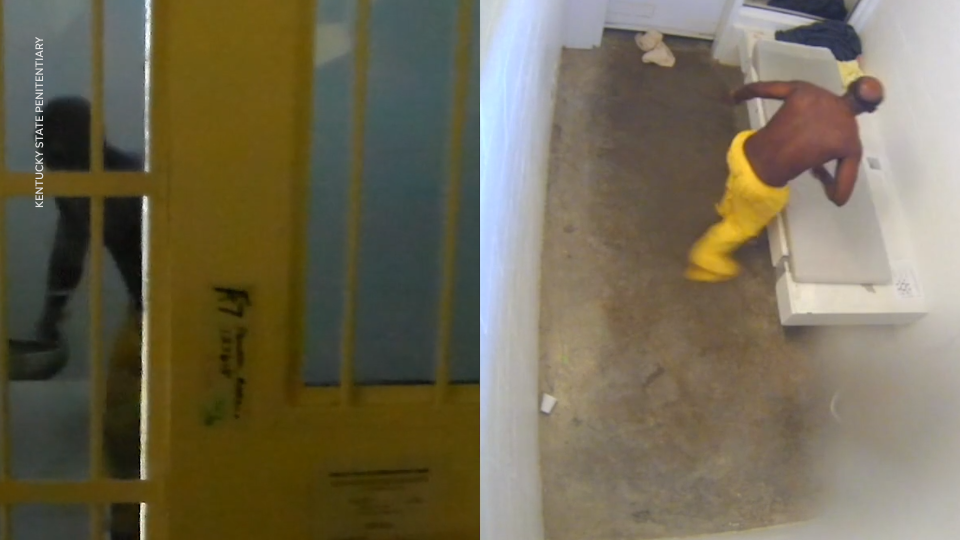

Instead, a 40-minute video obtained by USA TODAY showed a detention officer pepper-spray Penman three times in the face, then tase him six times – including with an electric shock that lasted 18 seconds. A team of six officers – none of whom had any extraction training – dragged Penman out of his cell.

Penman was put in a restraint chair, choked by an officer, and then covered with a spit hood as he gagged on residual pepper spray. He began making the harsh, grating sounds of a man dying. As he lay motionless and unresisting, a guard continued to press a stun shield against his face and body, a civil rights lawsuit alleges.

For 10 minutes after Penman stopped breathing, no one provided aid, Penman's family alleges in a civil lawsuit in a case that has been fought by state officials for five years.

"Penman spent his last moments on this Earth, soaked in pepper spray, shackled, in darkness, desperately trying to breathe, and clinging to life," attorneys representing his widow, Alice Penman, wrote.

Penman's family wants to hold prison officials accountable for not properly caring for him during his mental health crisis or intervening when they say his Constitutional rights were being violated by prison guards. His death raises questions about the adequacy of training prison guards receive on dealing with people who are suffering from mental illness and experiencing a crisis.

Corrections experts told USA TODAY that claims of medical neglect and mistreatment of the mentally ill are not only a problem in Kentucky, but are also endemic to the U.S. penal system, which was never intended or equipped to deal with the mentally ill. That's despite the fact that at least 26% of individuals in county jails and 15% of those in state prisons have a serious mental illness such as schizophrenia, severe bipolar disorder and depression, according to the Treatment Advocacy Center, a nonprofit that aims to eliminate barriers to treatment for the severely mentally ill.

At the federal level, mental illness is often underreported or underdiagnosed because once it is on the record, the prison becomes responsible for addressing it and providing care, said Elizabeth Sinclair Hancq, the Treatment Advocacy Center's research director.

"That sounds, most likely, maybe that was part of this as well," Sinclair Hancq continued. "His symptoms were being dismissed and ignored in part because of these pressures to not officially acknowledge individuals' challenges."

In an email to USA TODAY, Kentucky Department of Corrections spokesperson Katherine Williams said Penman was being housed at the time of his death in restrictive custody for fighting and assaulting staff.

"Due to Mr. Penman’s actions, Kentucky State Penitentiary staff were forced to intervene in order to stop Mr. Penman from continuing to seriously injure himself," Williams wrote.

Willams did not reply to questions about Penman’s lack of treatment, mental health history or the systemic deficiencies alleged in the lawsuit. None of the attorneys representing the defendants responded to requests for comment.

In the civil suit, attorneys for the prison officials argue that while Penman's death was tragic, he was so out of control that the team had extracted him from his cell after all other methods failed to get him to comply with orders and stop injuring himself. They deny Penman's rights were violated.

"Corrections staff had to stop Mr. Penman from continuing to injure himself because corrections staff have a duty to protect inmates — even from themselves," attorneys for the defendants wrote in court filings.

After state mental health hospitals were deinstitutionalized and closed down starting in the 1960s, "state prisons across the country became the state mental hospital, the largest one in any state. And local jails, the emergency room," said John Rees, the former commissioner of Kentucky Department of Corrections.

Evidence collected in a Kentucky State Police investigation into Penman's death was presented to a Lyon County, Kentucky grand jury in April 2018. The grand jury declined to take further action in the case or indict any of the involved prison officials for Penman's death because they found "no evidence of any criminal conduct," according to Kentucky State Police records obtained by USA TODAY in a public records request.

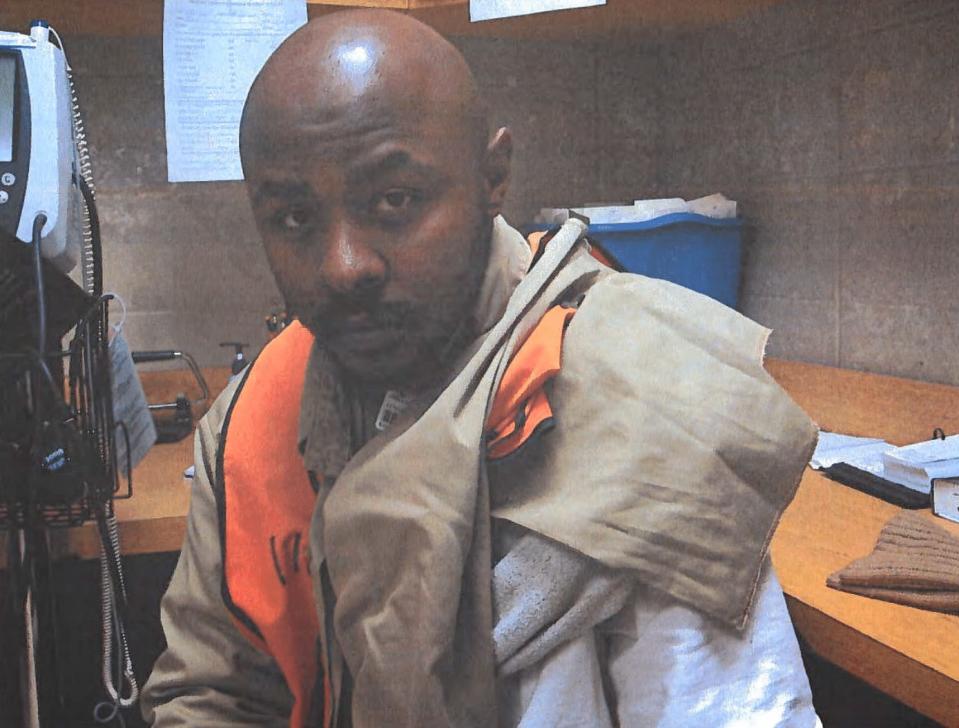

Penman, 39, suffered from multiple known mental health issues, including bipolar disorder, antisocial disorder and ADHD, none of which the Kentucky State Penitentiary staff was treating at the time, according to court documents and depositions reviewed by USA TODAY. He was eligible for parole later that year, according to the Kentucky Parole Board.

In a news release the day after Penman's death, Kentucky State Police said, "the only signs of trauma appear to have been self-inflicted."

But the medical examiner found that Penman experienced a partial collapse of the lungs and the whites of his left eye was speckled red from broken blood vessels because of the lack of oxygen. His death was ruled a homicide from asphyxiation because of neck compression, with blunt force trauma to the head and an enlarged heart as contributing factors.

"He's a symptom of a situation that exists throughout our country," Rees said. "Our mental health system does not work when it comes to violent, mentally ill individuals, period."

Weeks of deteriorating mental health

For weeks in the spring of 2017, Penman's mental health deteriorated and he appeared to be experiencing a manic state with psychotic features, according to court records. Prison staff said Penman was typically respectful and that such behavior was unusual for him.

A sudden change in behavior should have been a red flag, his family's attorneys said.

But Penman was never referred to a psychiatrist and his mental health was left untreated by Kentucky State Penitentiary staff, court records show. In fact, one of the medications he was receiving was not only not approved for bipolar disorder, but could ignite psychosis and a manic episode.

About three weeks before his April 25, 2017 death, Penman refused to return a food tray. Prison guards pepper-sprayed, tased and extracted him from his cell, placing him in a restraint chair for several hours. Two days after that, Penman threw a tray at staff and yelled "they're trying to kill me" while sweating profusely. He was pepper-sprayed again by prison staff, fell to the floor and started vomiting. Penman was again put in a restraint chair.

The next day, Penman "wrapped a sheet around his neck" and said he wanted to kill himself. He was put on a mental health watch in "segregation," which is similar to solitary confinement, but no medication management was provided.

On April 7, 2017, a mental health provider conducted a review of Penman in a 23-hour locked-down isolation cell and documented "recent self-harming" behavior like "banging his head on his cell door." Five days after that, Penman made a request for counseling and noted he felt "unstable and a part of the suicide squad."

Despite being diagnosed with bipolar disorder, anti-social disorder and attention deficit disorder, a different mental health counselor evaluated Penman through his cell door, she said he laughed and denied being suicidal. The day prior to Penman's death, Penman went on a hunger strike and the counselor again evaluated. According to court records, she wrote on April 24, 2017, that she believed Penman was "trying to present as psychotic" and "trying to confuse this clinician" by speaking in coded language about "they" being out to get him.

Video: California prisoners rush to save lives of fellow inmates

The mental health counselor said Penman was engaged in a "ploy" to remain in segregated housing "and off the yard until he can be transferred."

Penman was never referred to a psychiatrist and no medication was provided to treat his mental health, court records show.

Penman spent most of April 2017 locked down in isolation, including the afternoon of his death, according to court records.

Dominic Sisti, an assistant professor of medical ethics at the University of Pennsylvania, said the attitude adopted by prison staff seemed to indicate "deliberate indifference" to providing the right healthcare and resources for Penman.

"We've got the most vulnerable people in the most violent settings with the least qualified administrative people around them, trying to manage them and do the right thing in the face of a severe psychotic and psychiatric crisis," Sisti said. "And that’s just a recipe for brutality."

Sisti noted that often jails or prisons are the only places people get any mental health treatment, but it's often "just barely better than nothing" and generally inconsistent. In many cases, like Penman's, the lack of any real ability to deal with the mentally ill means that individuals who experience any type of episode are placed in solitary confinement – a practice that Sisti said is considered torture in much of the developed world.

A duty to care for the mentally ill

Penman's widow, Alice Penman, 44, learned about her husband's death from a cousin who saw news articles report his death as a suicide. But she didn't believe it, she told USA TODAY, because he was so close to finally getting out and meeting his granddaughter.

She said they had known each other since they were seven and he lived down the street. As childhood sweethearts, they loved sharing oatmeal cream pies together.

While in prison, the two would write each other, but when he was out, she said Marcus Penman seemed depressed by his time in prison.

"You can tell when a person has been locked up for a long time," she said.

In court filings, Penman's widow alleges that the prison staff and its supervisors violated her husband's Constitutional right as an inmate to adequate medical care and failed to intervene to prevent his death.

His widow alleges that the prison guards were "deliberately indifferent" to Penman's medical needs while he was in crisis and failed to urgently provide advanced medical care to him. The only nurse on scene remained at the edges or outside camera view for most of the incident. When prison guards pulled Penman from the restraint chair to begin chest compressions, they slammed his unsupported head repeatedly against the ground, the video shows. What medical care they did provide, came far too late, the lawsuit contends.

"When you lock somebody in a cage and take away the key, you’re now responsible for their wellbeing," said Dan Smolen, a civil rights attorney representing Penman's widow. "You have a duty to make sure they’re being taken care of."

In court documents, the defendants said that Penman bit and injured a guard once in the restraint chair, which is why the shield was required to be pressed against him. Smolen said there was no record of medical treatment provided to a guard or any indication Penman bit someone on video.

Cell extractions are notoriously dangerous operations, regardless of whether an individual is mentally ill or not. And in this case, the guards also had an obligation to stop Penman from continuing to injure, or even killing, himself, prison experts told USA TODAY.

But not one of the six officers assembled for the extraction team was trained for the job, according to their training records and depositions reviewed by USA TODAY. None of them had any training in placing an inmate in a restraint chair, and the officer who held the stun shield against Penman, had never used one before. The supervisor, who also tased and pepper-sprayed Penman, did not know how to discharge either tool effectively, according to depositions reviewed by USA TODAY and Smolen.

Kentucky State Penitentiary officials broke numerous state corrections policies, Penman's widow alleges, including failing to ensure officers were up to date on training for cell entry, the use of tasers and pepper spray; and failing to decontaminate Penman after administering a chemical agent by, for example, "flushing the affected area with copious amounts of water," per cell entry policy.

The lawsuit names the southwestern Kentucky prison's unit administrator Josh Patton; Lt. Kerwyn Walston, the commander of the cell entry team who deployed the pepper spray and taser; plus team members James Corley, Jason Denny, Michael Lamb, Steve E. Sargent, Jose Bailey, Robert Harris, and Steven H. Sargent. It also names then-Warden Randy White; Deborah Coleman, then-director of mental health for the state's Department of Corrections; and Cookie Crews, then-Kentucky Department of Corrections' Health Services Administrator.

All state employees have denied liability. The Kentucky Department of Corrections cannot be held liable because of sovereign immunity.

State officials argue in their court filings that staff, supervisors and state corrections leadership, should be granted qualified immunity, meaning they should not be held personally liable as government officials – unless they have violated a right that was "clearly established" in precedent at the time of the violation. Since Penman's death, Crews has been promoted to commissioner of the Kentucky Department of Corrections.

In an order issued last week, Senior Judge Thomas B. Russell of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Kentucky denied efforts by the prison guards to dismiss the case and said they weren't entitled to qualified immunity. Russell found that claims against the supervisory officials, White, Crews and Coleman, however, should be dismissed.

Russell found there was enough evidence that a jury should decide whether the unit administrator and his extraction team committed a variety of Constitutional violations leading to Penman's death, including the Eighth Amendment, which prohibits the government from imposing "cruel and unusual punishment."

The judge wrote, "any reasonable official would know that pressing a shield down on a prisoner’s face for eight minutes while that prisoner is subdued, no longer resisting, and in a state of respiratory distress/no longer breathing is an unreasonable method of maintaining control of a prisoner in a room occupied by at least six other officers."

Hidden behind prison walls

Unlike police violence, like George Floyd's murder by police in Minneapolis, inmate deaths behind prison walls – often in more rural areas of states – are by their very nature hidden from public views. Details of deaths are typically revealed only through litigation or limited disclosure by the prison itself.

And because state corrections can claim sovereign immunity from being sued, often that becomes a reason to dismiss a case, said Holly Harris, executive director of the Justice Action Network, the largest bipartisan criminal justice reform organization in the United States. In such cases, the veils of secrecy are never lifted.

Eldon Vail, who previously headed Washington State's Department of Corrections, said prison guards did "way too much" and that Penman "was put at risk by the tactics they used." He said there should have been immediate medical evaluation after Penman's continual head slamming.

"There's no attempt to communicate with him," Vail said, noting officers had many opportunities to enter the cell earlier, such as when Penman knocked himself to the ground.

"I don't know of any use of force training that would authorize" a shield over his face in the restraint chair, Vail said.

Officers have the right to put their hands on other peoples' bodies for a cell extraction if absolutely necessary, Vail said, but they should "make it quick and clean as possible."

Gary Raney, a nationally recognized use of force consultant who works as a federal monitor in jails, said he was "very bothered" by the unconventional neck restraint used by a prison guard and that "nobody seems to be monitoring" Penman when he became unresponsive.

"The hold is not something that is taught," Raney said. "There's nothing that justifies pressing on the airway."

Raney also noted the "inordinate amount of time" it took for the cell extraction team to get Penman hooked into the restraint chair properly, which Vail called a training issue.

"I see this sort of thing all the time," Raney said, "where you have poorly trained officers in, so many respects, mental illness, deescalation techniques, proper use of force planned use of force," how to use pepper spray.

The fact that Penman's left eye had blood in the whites and that viewers can hear the sound of his obstructed breathing on video makes Penman's cause of death "absolutely sure," said Dr. Jeffrey Keller, a nationally recognized correctional medical expert who is a fellow of the American College of Correctional Physicians.

"They choked him to death," Keller said.

'The death penalty' for a drug offense

Penman was sentenced to prison in 2005 for drug-related charges, including trafficking cocaine. Under the state's "persistent felony offender" law – essentially a "two strikes" sentencing policy – his sentence was doubled to 20 years.

Kentucky has one of the highest per-capita rates of incarceration in the world, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. A disproportionate number of those locked up are Black, Native American or Hispanic.

There are four times as many people with severe mental illness incarcerated in Kentucky prisons than are hospitalized in state psychiatric facilities, said Harris, the executive director of the Justice Action Network.

In Kentucky, after an inmate dies in state custody, policy requires a "critical incident review" to determine whether policy or legal violations occurred. But in Penman's case, the Kentucky Department of Corrections failed to conduct one, according to sworn testimony reviewed by USA TODAY.

Penman's case bears similarities to others involving mentally ill inmates under state care.

In an incident four years prior to Penman's death, 30-year-old Steven McStoots, who suffered from a serious mental illness, was killed at a different facility by Kentucky prison guards in the process of extracting him from his cell. No one was charged in McStoots' death, which is the subject of an ongoing civil suit.

In 2014, another mentally ill inmate, 57-year-old James Embry, starved to death over roughly five weeks as medical staff and prison guards watched without apparent concern, according to a critical incident review conducted after his death.

The review found that the consensus among staff had been that "his behavior was strictly goal-driven and was an attempt on his behalf to manipulate his housing situation." The review found that even if this was initially true, it should have become clear that "his well-being was in serious jeopardy" and there should have been a medical response.

'TOO TOUGH' ON CRIME?: A Kentucky law is flooding prisons and costing taxpayers millions

In Penman's case, Harris of the Justice Action Network, said the lack of medical response to his mental health crisis shows the system is "set up to fail" because of a lack of training, resources and expertise.

"A nonviolent drug offense should not warrant the death penalty, and that's what happened here," Harris said.

An expert witness for Penman's family, Dr. Richard Sobel, concluded that the state's failure to provide "advanced life support...sealed Mr. Penman's fate." But with the proper care, he would have recovered without substantial physical disability, he said.

Sobel has practiced emergency medicine for four decades and worked as an attending physician in charge of the prison medicine unit at the emergency department of an Atlanta hospital, served as medical director and attending physician at an Alabama prison, and was attending physician at a Florida correctional institute and jail.

While in prison, Penman missed out on the funerals of his brother and his mother, his wife said. He seemed depressed because he was in prison, but he never told his wife what his life was like behind bars. She said he didn't want her to worry.

When his wife finally learned how her husband died from Smolen – who only discovered what happened during a deposition for another case – she said "it just broke my heart, and I just cried."

Alice Penman said she's still never heard from any state official about Marcus' death.

"I don't feel like he deserved what he got, how he was treated up until the moment of his death," she said. "I feel like there could have been a better way to handle that situation."

"You've got people that’s locked up, they might have done some bad things, but they're still human beings no matter what, they’re still humans. And family deserves to know what happens to family," she said.

Tami Abdollah is a USA TODAY national correspondent covering inequities in the criminal justice system. Send tips via direct message @latams or email tami(at)usatoday.com

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Lawsuit: Mental illness in prisons goes untreated, resulting in deaths