Mercedes-AMG's "Dual-Axis Steering" Has Even More Advantages Than You Thought

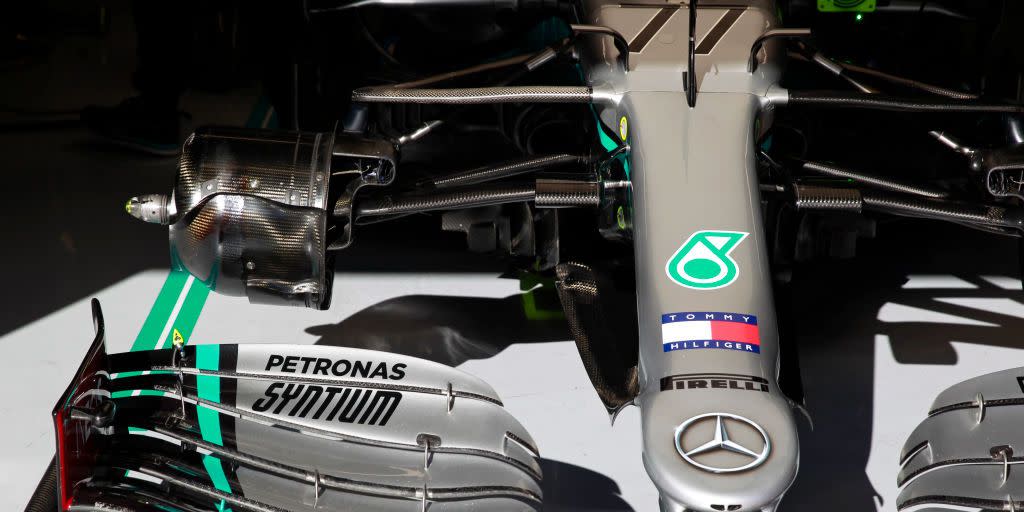

Long after the regulatory loopholes were closed that brought us the F-Duct and double diffusers, the Mercedes AMG Petronas Formula 1 team stoked the dormant interest in grand prix innovation last week when an on-board camera revealed an oddity within the cockpit of reigning world champion Lewis Hamilton.

The Briton was captured pushing his steering wheel—and the steering column and, we assume, the steering rack—fore and aft with intent while lapping at the Barcelona circuit in his new W11 chassis.

Mercedes F1’s ‘DAS’, believed to be an acronym for Dual-Axis Steering, is a conceptual cousin to the drag reduction system (DRS) found at the back of every F1 car. DRS is an electronic system triggered by the driver on the steering wheel that temporarily flattens the upper rear wing element on long straights to slash aerodynamic downforce and drag.

Only permitted in a limited number of zones defined by F1 at each circuit, DRS was implemented as a tool to promote more passing by increasing the top speed for drivers who get within one second of the car they’re pursuing. If Driver A is less than one second behind Driver B entering a DRS zone, the system can be triggered with the press of a button: the upper rear wing element opens, unneeded downforce and drag is shed, and a burst of overtaking speed is produced.

With DAS, which has already been banned for 2021, the Mercedes F1 team has applied the thinking behind DRS to reduce the mechanical drag—tire scrub, to be precise–caused by the alignment of the front suspension. And unlike DRS, DAS isn’t restricted to specific zones around each circuit; it’s available to Hamilton and teammate Valtteri Bottas at all times.

A post shared by FORMULA 1® (@f1) on Feb 20, 2020 at 4:43am PST

Understanding the reasoning behind DRS and its value is easy. By removing some of the useless downforce and drag that does nothing to help an F1 car while accelerating on a straight, the car goes faster. In drag racing terms, DRS creates shorter elapsed times when it’s activated.

DAS is a bit more abstract, and yields a smaller E.T. gain than DRS, but its value in reducing ‘drag’ caused by the front tires scrubbing against the track surface and, to a lesser degree, aerodynamic drag created by the tires, should not be underestimated. The only thing that won’t be known is how much of an advantage DAS offers until the first race weekend of the season gets under way. In testing at Barcelona, and any other outing where other teams are present, it’s highly unlikely we’ll see Mercedes unleash the maximum capabilities of the W11.

As F1’s cars grow more similar each year, lateral thinking is required to find the tiniest of advantages to distinguish one model from the next, and in DAS, we have a case where Mercedes F1 asked itself if an old and accepted performance penalty, one that’s been faced by every team since the dawn of motor racing, could be resolved. In road racing, aligning the front tires, the ‘toe’ adjustment, to point each side outward to a small degree, is standard. It’s called ‘toe-out.’

And while using toe-out is a critical aspect of making a car turn, it induces the aforementioned scrub, which slows the car. In having the front tires skewed outward on the straights, the oncoming air hits wider objects; if toe-out was removed, and the tires were pointed straight, a slightly narrower object would interrupt the air and make a smaller disturbance.

Despite being tiny areas of inefficiency to optimize, giving Hamilton and Bottas the ability to pull back on the steering wheel and remove the negatives associated with toe-out on the straights is a radical step forward in steering design that offers multiple improvements.

To picture the friction and forces that interact between a tire with toe-out and the road it travels over in a straight line, think of a shopping cart being pushed down an aisle. It’s likely, at some point, you’ve had cart with a faulty front wheel that wobbles and shakes, or fights to turn the cart left or right. Unlike the other three wheels that are pointed straight ahead and roll smoothly with minimal effort, that one out-turned or in-turned wheel is the one that requires more physical exertion to overcome and correct its scrub.

This, in racing terms, is what internal combustion engines and kinetic energy recovery systems are forced to overpower with the front suspension and the modestly out-turned front tires. Rather than rolling down the straights with the tires pointed in perfect parallel to the corner ahead, toe-out intentionally introduces that bad-shopping-cart-wheel friction on the front tires because it’s a necessary component in cornering.

Reducing tire scrub by using as little toe-out or toe-in as possible has long been a practice among teams at the Indianapolis 500. With the vast majority of the four-turn, 2.5-mile oval comprised of straights, every effort is made by teams to strike the best balance between cornering speed and straight-line speed to reap the rewards of optimal performance in both conditions.

Seeing the hyper-diligent practice of Indy 500 scrub reduction applied to road racing fascinates one of IndyCar’s great race engineers, Craig Hampson, who won four Champ Car titles with Sebastien Bourdais and works today as Arrow McLaren SP’s Race and R&D Engineer overseeing its NTT IndyCar Series program.

A veteran of Indy 500 race engineering, Hampson understands what the Mercedes F1 team is seeking to alleviate with DAS, and believes there’s a few speed-generating solutions it could provide.

“I'm more inclined to say it is a straight-line speed tool, insofar that reducing the toe-out that occurs down the straightaway will improve the straightaway speed,” Hampson tells Road & Track. “It will also reduce the heating of the front tires, and therefore they'll have better longevity.”

Hampson has another idea on where DAS could be a game changer.

“It also occurs to me that maybe they want to run more front toe-out than you would usually do for the corners, which would help turn the car more, but nobody does this because it has an overly negative effect on tire scrub down the straight, which hurts straightaway speed, and hurts the tire temps,” he adds. “But if they've found a way to alleviate that [with DAS] by making the problem go away down the straightaway without the tire scrub, it could be a powerful tool.”

Diving into the science of tire scrub, the value in its elimination on the straights, and how the intersection of toe-out and camber settings on the front tires come together makes for a fascinating download from Hampson.

“Tires mainly produce a lateral force, right? And that lateral force is coming from the slip angle of the tire, which is the angle at which the tire’s at, versus the direction in which the car is going on the road,” he says.

“There's also camber thrust. So there's lateral force due to the camber thrust from the angle that the tire is to the road. So, if we’re at Indianapolis, and we speak about the right-front tire, it is producing sideways force even as it drives down the straightaway because of the camber thrust. So when you steer the tire, that tire is no longer parallel to the center line of the car and therefore the axis at which the sideways force–the thrust–is pointing is no longer exactly perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the car. And so a very small part of that vector is pointing in the way that ends up slowing the car.”

With toe-out and camber thrust acting like small, friction-based parachutes with the front tires, DAS frees the W11 from those performances losses that add up to an unspecified amount of time forfeiture on each lap.

“If you put those two things together, it's basically a contribution of the lateral force of the tire resisting the forward movement of the car,” Hampson continues. “So the more you steer the car and the more lateral force you're getting out of that tire, the more you are actually slowing the car down. It's logical when you think about it, right? You know you're going to make lateral force and therefore you don't get anything for free, so some of that comes with friction that slows the car down. But it's because the tire is no longer aligned with the direction that the car is going.

“So if you can achieve your cornering with less steering, less slip angle of the tire through the corner, you actually end up with less scrub and you lose less speed through any significant corner the Formula 1 cars navigate. If you watch the cars at Indianapolis, they slow down in the corners, even if the driver is full throttle. Well, it's slowing down because of the steering of the tires, the slip angle of the tires and the fact that the lateral force in the tires is resisting the forward movement of the car. So if we can reduce all of that, we go faster through the corner.

“Mercedes is trying to do the same thing, but just thinking about it on the straightaways. If we straighten out the toe and put it at whatever the correct angle is so that the thrust from the tire is exactly perpendicular to the longitudinal center line of the car, then it's not going to slow the car down.”

With DAS engaged, Mercedes F1 engineers made swift work of quantifying its real-world benefits. Using on-board performance data generated by Hamilton and Bottas with DAS disengaged, a fast reference lap would serve as the benchmark to measure the elapsed-time gains produced by the W11 on laps with DAS enabled on the straights.

Keeping the private nature of testing alongside fellow F1 teams in mind, it would be expected for Mercedes to ask its drivers to mask the lap-time advantage DAS holds by engaging the system in select sections on one lap, then different sections on another, and so on, to avoid completing a full lap with DAS employed on every straight. By capturing DAS data in chunks over a series of laps, it keeps Ferrari, Red Bull, and other teams from accurately benchmarking its benefits.

The same partial-lap testing practice is done with or without a new invention like DAS; drivers are routinely instructed to go hard in certain portions of a track where engineers want to receive performance feedback, and tell the driver to lift or coast elsewhere to skew the car’s unbridled capabilities in front of their rivals.

With the DAS data in hand and the laps stitched together for review, a simple compare-and-contrast of the speed differences on the straights has given Mercedes a clear view of its value which will be revealed during the opening F1 race weekend of the season March 13-15 in Melbourne, Australia.

“With DAS working, the only front rolling resistance you're going to have is just the rubber on the road and the grease in the wheel bearings,” Hampson explains. “In fact, they'll be able to know it by watching the tire temperatures. Whatever temperature results in the coolest, coldest tread temperature, is probably the least amount of friction. So they were watching all their temperature sensors, the thermal cameras, and seeing the different from when they don’t use [DAS] and the higher friction and higher temperatures the car generates.”

The last item of interest with DAS for now is how the system is engaged and disengaged by Hamilton and Bottas. Although the steering wheel was captured being slid fore and after, a locking mechanism would be needed to hold the wheel in place in both positions as it would be impossible to steer with accuracy if the column was allowed to slide back and forth while aiming for apexes.

“It has to positively lock in one way or the other,” Hampson says. “And the driver better remember to put it back in the right position or the toe is not going to be in the right place for the corner. Just think of the possibilities. You could have a high-speed steering setting that’s slower to prevent upsetting the car and a low-speed steering setting for the slower corners to induce quicker chassis reactions. There's just all sorts of things you could do with this.”

Hampson, who rates as one of the great minds in open-wheel racing, salutes the unsung design engineers who’ve found a creative solution to an age-old nuisance.

“There are some clever engineers somewhere in that giant building of a thousand people, whether he or she be young or old, who deserves praise for thinking outside the box and coming up with an idea, and I like it,” he says. “Because it's not actually that complicated a system, but they're all going to have to scramble to design one and get it implemented as soon as they can. So, that's a pain.

“And that's an expense and does it actually make the spectacle any better? Probably not. So it's exactly the kind of thing that owners and rules makers want to outlaw. But as an engineer and a fan of the sport, I think it's great. I wish there was more stuff like that we could do.”

You Might Also Like