At the Mercer Museum, the gallows of Bucks County on display as remnant of 'tool of social control'

Pity James Linzi. A Doylestown barber distressed over losing his job, he wrote a suicide note, shot his pregnant wife, Ida, then turned the gun on himself.

Though Ida died, Linzi didn’t. He was rushed to a Philadelphia hospital, nursed back to health, tried, convicted and sentenced to death by hanging.

“So he’s one of those cases where they kept him alive so he could be executed,” said Cory Amsler, standing beneath the gallows through which Linzi dropped at 10:34 a.m. July 14, 1914. His last words: “Into thy hands, O God, I give my soul,” according to a newspaper account of the time.

Amsler, vice president of the Mercer’s collections and interpretations, said Linzi was also a bigamist.

“He had another family in New Jersey, which Ida knew nothing about,” he said.

Of the weird and intriguing items in the museum (including a vampire killing kit and witches’ books of spells, both white and black magic), the full-scale wood gallows might be the eeriest, certainly among the most macabre.

But the sight of the hanging platform wouldn’t have surprised Bucks Countians of that era.

“For a long time, hangings like Linzi were done publicly. They were something that thousands of people might come to. It was a large, public spectacle,” Amsler said.

The Linzi case was a sensation, and it was also the last execution by hanging in Bucks County.

As methods of capital punishment changed in Pennsylvania, public hangings in Bucks County were stopped in 1838. They were carried out more discreetly behind the high stone walls of the old county prison on Pine Street (today the Mitchener Art Museum). Entry was granted by invitation only, and those invited were government authorities, family members, defense and prosecution lawyers, and Linzi’s priest, who briefly prayed with him atop the trap door before a bolt was pulled “which shot him into eternity,” according to an account published in the Intelligencer.

More enlightened methods of death came into vogue, with Pennsylvania preferring the electric chair, which was considered modern and more humane. Those new methods had been evolving over decades of reform. By 1914, Bucks County didn’t even have its own gallows, instead borrowing one from neighboring Northampton County as needed.

“Bucks County had long before that dismantled and disposed of its gallows,” Amsler said. “Once the Linzi hanging was done, it went back up the road to Northampton.”

It’s not known how many swung from it.

“We don’t even know its exact vintage,” he said.

After Linzi was hanged, and the gallows returned, the only person who saw value in it was Henry Chapman Mercer, an archeologist, tile maker and collector of pre-industrial hand tools from the 19th and early 20th centuries. Like the gallows, hand tools that were common to American homes, farms and businesses were vanishing as industrial technology took hold, rendering old ways obsolete.

“Henry Mercer, who at that time was in the process of building (the museum) wanted the gallows,” Amsler said. “He wanted to have that object represented in his museum collection. He was able to negotiate with the commissioners in Northampton to donate it.”

Each item in Mercer’s collection had to pass one test: it had to have a function. A hammer is a tool of carpentry. An anvil a tool of metalworking. Mercer wanted every pre-industrial tool that met a need.

“Mercer saw this piece as a tool of punishment. A tool of social control, a tool of capital punishment,” Amsler said.

Murder mystery:A bloody corset, a gun and a purse: Was there a murder at Yardley's Continental Tavern?

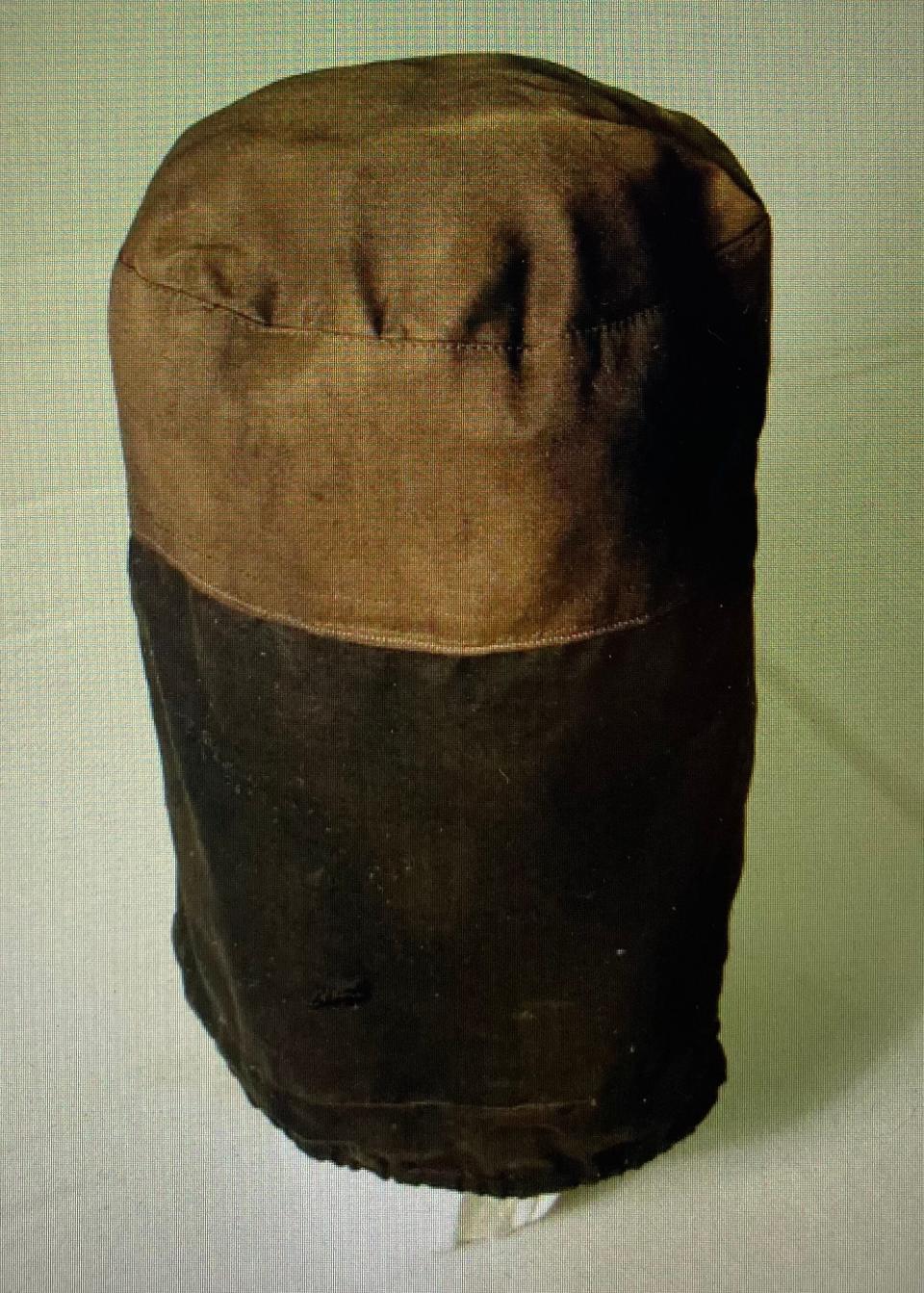

“When the gallows was first installed here, there was actually a noose hanging from it,” Amsler said. But when kids got into the museum and were found playing on it, it was removed.

The gallows is on an upper floor, north side, not really apparent until you’re standing beneath the trap door through which Linzi dropped, dangled and died.

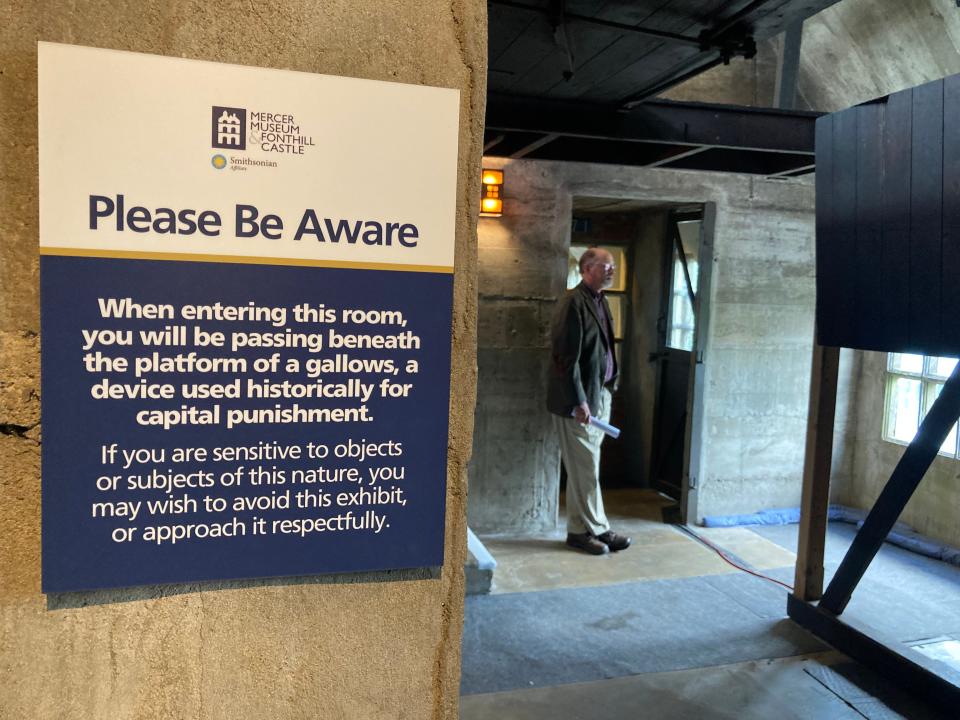

“A lot of people don’t even realize they’re standing under a gallows when they pass throught here,” Amsler said. “We do have the trigger warning outside, because there are people who, if they knew, would not walk under it or, when they walk under it and realize what it is, they become upset.”

If you go to see it on your downtime over the holiday, be warned.

JD Mullane has been a columnist and reporter at the Bucks County Courier Times since 1987. Reach him at 215-949-5745 or at jmullane@couriertimes.com.

This article originally appeared on Bucks County Courier Times: Gallows of Bucks County are a remnant of 'tool of social control' at Mercer Museum