Company in charge of Louisville jail health care when inmates died is back, with a new name

Louisville Mayor Craig Greenberg in April announced a search for a new health care provider for the city’s jail as part of a series of “seriously needed reforms” at Metro Corrections.

The announcement followed a spate of 12 in-custody deaths in less than a year spanning 2021-22 and calls from jail reform advocates for the city to sever its contract with Wellpath, the current health care provider.

Nearly eight months after that press conference, the city made its pick: a company called YesCare.

Like Wellpath, YesCare is a giant in the corrections medical care industry. Like Wellpath, it is based in Tennessee. And like Wellpath, it is a company steeped in controversy.

YesCare formed after its predecessor, amid mounting lawsuits alleging substandard prison care, restructured in 2022 in a bankruptcy move called the “Texas Two-Step.”

The maneuver involved offloading liabilities onto a new company while executives from the original company formed yet another company, YesCare, from which to do business.

Opponents of "Texas Two-Step" tactics say they allow companies like Corizon, YesCare’s predecessor, to dodge debts from legal claims and bills.

Corizon was the health care provider for Louisville Metro Department of Corrections up until 2013, when they departed following an uptick in deaths at the facility.

At the time, jail leadership said the company made missteps, and an internal investigation determined Corizon employees “may” have contributed to at least some of the seven in-custody deaths in 2012.

“Seeing that a corporation like that is allowed to remake themselves over and over again, changed their name, but they still haven’t changed their internal policies — that’s terrible. That’s not what we need,” said District 3 Metro Councilwoman Shameka Parrish-Wright, who also serves as the executive director of VOCAL-KY, an organization focused, in part, on ending mass incarceration.

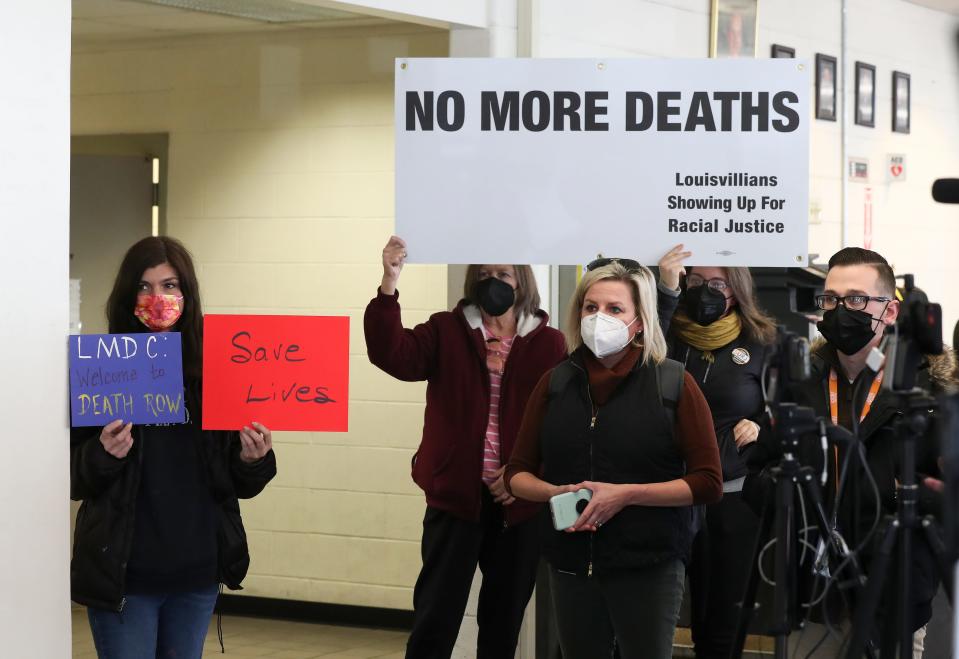

VOCAL-KY is part of the Community Stakeholders for Change at LMDC, a coalition formed during the recent surge in jail deaths that also includes the ACLU of Kentucky, Black Lives Matter and others.

In a statement to The Courier Journal, the coalition’s health care committee said they voiced concerns to Metro Government "about the financial practices of private equity correctional health firms, like YesCare and Wellpath."

Their cautions came in tandem with a report, commissioned by Metro Council, that encouraged the city to move away from corrections health care corporations to improve the quality of care.

But the selection of YesCare points to a stark reality: Transforming jail health care is difficult, and the industry is dominated by only a handful of companies, all of which, critics say, have their share of problems.

“Frankly, it’s like a merry-go-round among them,” said Corene Kendrick, the deputy director of the ACLU’s National Prison Project. “They change names, they acquire each other. Some of them are subsidiaries of publicly traded companies on Wall Street. Others, like Corizon — now YesCare — are owned by private equity hedge funds. So, all of these entities that are getting these contracts are just in the business of making money for their shareholders. And that is extremely problematic.”

A spokeswoman for the Mayor’s Office declined to answer questions about the selection of YesCare, citing ongoing negotiations with the company. Metro Corrections also declined to comment because of the negotiations.

The city’s health department, which, according to a request for proposals put out last year, was set to evaluate bids alongside Metro Corrections, referred The Courier Journal to the Mayor’s Office.

YesCare did not respond to interview requests.

'Mistakes were made' by Corizon at LMDC

Over the course of 2012, seven incarcerated people died at Louisville’s jail amid allegations that its health care provider — Corizon — was providing substandard care.

In December 2012, The Courier Journal reported six Corizon staff members quit after an internal investigation determined they “may” have contributed to the deaths of two incarcerated people.

At the time, then-LMDC director Mark Bolton said he “concluded there were some delays relative to medical protocols” resulting in it taking too long for people to see doctors.

In an email to staff at the time that would later come out as part of a lawsuit, Bolton said “mistakes were made by Corizon personnel and their corporation has acknowledged such missteps.”

Later, even more blistering criticism of Corizon would come forth.

“The more we looked into it, the more disturbed I was getting as to some of the service delivery gaps in the health care of these individuals,” Bolton told The Courier Journal in a February 2013 story about allegations of substandard health care at LMDC.

That same story noted Corizon, when previously named Correctional Medical Services, had “touted its track record of saving the city money by minimizing inmate trips to the hospital” while renegotiating its contract in 2010.

As Corizon faced scrutiny, lawsuits piled up, including one from a Louisville woman who had her fingers and legs amputated after she said she begged medical staff to let her see a doctor as she suffered from an infection, but received medical care only after she was released from custody. The case settled in 2013.

Facing backlash, Corizon launched a website — louisvillejailnews.com. According to an archived version of the site, the company asserted it had never been found responsible for “having provided substandard care to, or causing injury of any kind” to anyone incarcerated at LMDC.

In September 2013, The Courier Journal reported Corizon unexpectedly let its $5.5 million contract with Louisville expire without seeking a renewal.

Bolton told The Courier Journal at the time he was surprised Corizon had not proposed an extension and that the company had not offered him an explanation as to why they were leaving.

Soon, a company called Correct Care Solutions would take over. That company would later rebrand as Wellpath following an expansion.

According to documents obtained through an open records request, Wellpath’s last contract extension is set to expire on Feb. 28.

Corizon and its predecessor, Correctional Medical Services, were longtime providers at Lexington’s jail, with the latter serving the jail starting in 1992. Since Corizon’s restructuring, Lexington is working with YesCare.

“When YesCare was formed, we did not notice any changes outside of the rebranding,” Lexington Community Corrections spokesman Maj. Matt LeMonds told The Courier Journal in an email.

In a statement, Chief of Lexington Community Corrections Scott Colvin said he found YesCare’s services “very good.”

The Texas Two-Step

In 2022, after facing costly lawsuits, Corizon restructured, forming a new company called Tehum that absorbed Corizon’s liabilities.

Meanwhile, Corizon executives formed another company, YesCare, according to USA Today.

While Tehum was weighed down with debts and filed for bankruptcy, YesCare was given corrections health care contracts across the nation.

In court filings, YesCare has argued it is a separate entity from Corizon, is not Corizon’s alter ego and should not be responsible for liabilities incurred by Corizon.

Despite those claims, and despite existing on paper for only a short amount of time, YesCare’s website highlights its “40 years” of experience providing health care at 475 correctional facilities nationwide, which, according to USA Today, represents Corizon’s achievements.

According to USA Today, Corizon frequently used an “indemnity clause” in its contracts, promising to cover costs from lawsuits. But with the restructuring, more than a dozen government agencies have been stuck with bills the company promised to pay.

By filing for bankruptcy, Tehum hit the brakes on claims against Corizon.

In October, nine U.S. Senators — including Bernie Sanders, I-Vt; Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass.; Dick Durbin, D-Ill.; and Cory Booker, D-N.J. — wrote a letter condemning Corizon’s “abusive” restructuring strategy.

“Rather than facing victims and their families in court, Corizon attempted to shield itself by employing the so-called ‘Texas Two-Step,’ a maneuver through which companies leverage bankruptcy proceedings to attempt to evade liability,” the lawmakers wrote.

Last year, Tehum agreed to pay more than $37 million to settle claims against it, tens of millions of dollars short of what it owed.

However, settlement proceedings stalled when the federal bankruptcy judge in the case resigned after failing to disclose he was involved in a romantic relationship with an attorney representing YesCare.

Mediation restarted in November.

Meanwhile, attorneys for prisoners and their families suing Corizon are calling Tehum’s bankruptcy push a “fraud” and asking for it to be thrown out.

“Bankruptcy is not a tool to prey on widows. This case is an affront to basic principles of justice and dignity that every person deserves under the Constitution,” they wrote in a Jan. 16 motion.

In an October report, the Private Equity Stakeholder Project warned a successful Texas Two-Step by Corizon could have far-reaching consequences.

“If Corizon is permitted to benefit through its division and bankruptcy, it may clear a path for Wellpath and other poorly performing companies to begin [anew] with a blank slate and new name," the report states. "Corizon Health, YesCare, Wellpath, and any other healthcare providers seeking profits from prisons and jails should be held accountable if they are found liable for harms created by poor services.”

How was YesCare selected?

Last year, in a 457-page investigation into jail deaths commissioned by Metro Council, former FBI agent David Beyer concluded LMDC was “incredibly ill-equipped to provide adequate medical care to inmates — both from a building design and current protocols in place.”

Beyer found Wellpath patient records were incomplete. He also found a lack of communication between staff and a lack of qualified staff to deal with mental health issues at the jail.

He recommended the city look into having a teaching hospital take over medical services at the jail, as happens in some parts of the country.

If that wasn’t possible, Beyer suggested they at least explore having medical or nursing students rotate through the jail to help with staffing and “help maintain awareness of new medical trends, techniques and best practices.”

While Metro Corrections declined to comment on the selection process, in an interview in November, LMDC Director Jerry Collins told The Courier Journal multiple bids were submitted.

“Don’t hold me to this, but I think there was a total of seven,” he said.

According to the request for proposals issued last year, 30% of the evaluation of bids would come down to price. Twenty-five percent would be based on qualification and references, which included, among other things, an evaluation of the company’s corporate stability and recent litigation history.

Clinical utilization management and compliance reports would account for 25% of the evaluation, and scope of work and innovation in jail clinical management would represent the remaining 20%.

Kendrick, the ACLU National Prison Project deputy director, said private health care companies are problematic because they often win flat-rate contracts that can encourage substandard care.

“It creates this perverse incentive to cut costs, cut corners wherever you can, because that’s how much the company is getting regardless,” she said. “Every cent that they save becomes pure profit.”

When jails change from one company to another, she added, staff often stays and little changes.

“All that really changes, that I’ve seen, is that you go into the facility and there’s a new corporate logo slapped on the wall,” she said.

On YesCare’s website, a job listing welcomes Metro Corrections “transitioning employees” and requests “all current staff members” at LMDC to submit an application.

Reach reporter Josh Wood at jwood@courier-journal.com or on Twitter at @JWoodJourno.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Louisville moving from Wellpath to YesCare for Metro Corrections care