A message from the plants: US is getting a lot warmer, new analysis says

DENVER ‒ For millions of Americans, summers are getting longer, winters are getting warmer and the impacts are showing up in their front yards.

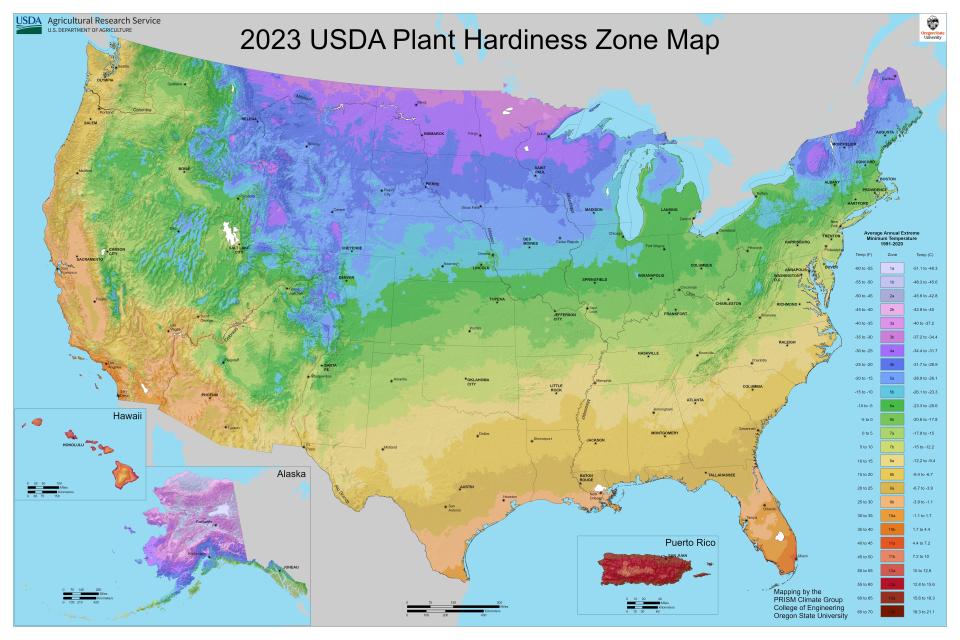

A recent analysis by federal scientists shows that half of the country has seen its average lowest winter temperature rise by as much as 5 degrees in some areas over the past 30 years, altering what can grow where, particularly in areas normally prone to frost or freezing temperatures.

The data, reflected in the updated Plant Hardiness Zone Map in November, helps gardeners, farmers, insurers and other officials decide what to plant, how much to charge farmers for crop insurance and whether to expect insects like ticks carrying Lyme disease to continue migrating north. This was the first map update in 10 years.

In Arizona, heat keeps getting worse

At Janna Anderson's 17-acre South Phoenix Pinnacle Farms in Arizona, she's already begun replacing heat-killed peach trees with citrus trees that can handle hotter temperatures.

"It really pushed a lot of those trees over the edge," Anderson told the Arizona Republic, part of the USA TODAY Network. "This year it didn't matter how much we watered them."

Last year, Arizona had its most consecutive 110-degree days, most consecutive 90-degree nights, and hottest month ever, according to the National Weather Service. An analysis of the plant hardiness trend data by Davey Tree Service predicts that southern Arizona growing conditions will keep getting hotter over the coming decades, as will large portions of central and northern California, much of the south, the Great Plains and the mid-Atlantic states.

Although the map's creators caution that their analysis shouldn't directly be used as evidence of climate change because it only covers three decades, other experts say it reflects a snapshot of that slow-growing reality. Climate scientists prefer to use 50-100-year time spans to measure climate change, federal officials said.

Changes like this are what you would expect in a warming world

Experts say humans aren't good at comprehending how small changes add up over time and tend to focus on major disasters supercharged by climate change – like stronger hurricanes, bigger floods, or droughts. Climate scientists say the majority of the continental United States will grow warmer and drier over the coming decades, although some areas will see more rain and others may experience localized cooling.

"It tends to take an extreme event for the trends to become meaningful," said John Nielsen-Gammon, the Texas state climatologist. "Extremes are rare enough that it’s hard to actually perceive a risk."

The new plant hardiness map reflects that nuance through the impact of tiny temperature changes on plants. The map's creators said more comprehensive data collection and the inclusion of more urban "heat islands" helped reflect the higher temperatures found in half of the country.

Higher temperatures have effects on plants, animals and people

While some climate-change skeptics have noted that the higher levels of heat-trapping carbon dioxide can help plants grow faster, federal experiments show higher CO2 levels under drought conditions also made the plants' fruits and grains less nutritious.

In addition to changing what plants can grow where, warmer temperatures in winter are allowing disease-carrying ticks to spread north. Since 1991, the incidence of Lyme disease has doubled as ticks have moved north and east from southern New England, with Vermont and Maine seeing dramatically higher incidences of the infection because the ticks are no longer freezing to death during winter.

California state climatologist Michael L. Anderson said more and more people are noticing the subtle changes around them, especially during what he calls "threshold" situations that unravel with larger wildfires, tougher droughts, or unexpected flooding.

"They come to me and say, 'I don't remember it being like this,'" Anderson said. "And I say that's because it hasn't been like this. You hit a threshold and all of a sudden things behave differently."

Contributing: Clara Migoya, Arizona Republic

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: US warming enough to affect what plants grow where, feds say in map