Metro Detroit's quality tap water helps residents, bottlers save money

She'd always been nervous about drinking tap water.

To Kari Rasmussen, of Grosse Pointe Park, and to her adult son, Ansel Rasmussen, it smelled and tasted like chemicals — "chlorine, I guess, and maybe something else," she said.

They weren’t the only family members who noticed. Mother and son can’t forget how, when they moved to Michigan from Maine, you could lead their dogs to water, but they wouldn’t drink.

“They just wouldn’t. They’d go outside and eat snow,” Kari Rasmussen said. The canines did that until the first spring thaw, after which they relented and accepted tap water. Still, family members grew to rely on bottled water, an expense they endured for years, she said.

“I know most people around here drink from the tap. Maybe we’re more sensitive” to the smell and taste. Yet, mother and son recently decided to save cash and start drinking tap water after doing two things, which anyone can try:

First, they put tap water in glass pitchers and let it sit on a counter covered by a dish towel for a day. Bingo, the faint smell and taste of chlorine was gone.

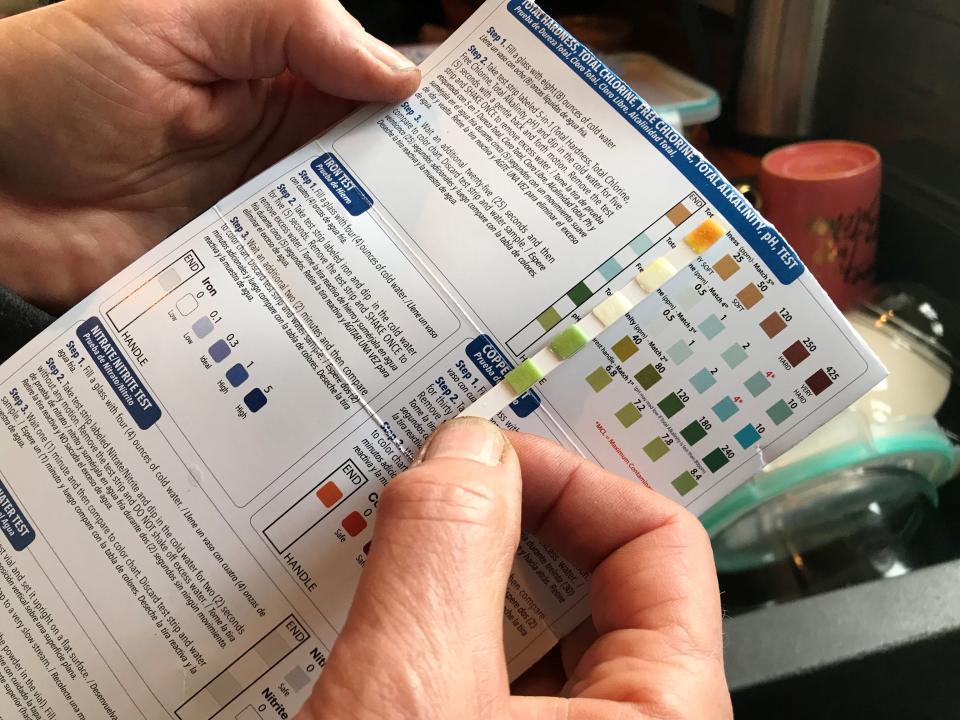

Second, they ran their tap water through an inexpensive, over-the-counter testing kit. Seeing no adverse results in the battery of 14 tests gave them confidence in the purity of tap water, which for most residents of southeast Michigan comes from the giant Great Lakes Water Authority. That entity, known as “GLEE-wah” for its initials GLWA, took over water and sewage operations after Detroit’s bankruptcy.

“I feel really good about this,” Kari Rasmussen said. She was surprised at the improved taste when she left tap water in pitchers to air out, like fine wine.

“My coffee is even smoother,” she said, after a Free Press reporter suggested the airing-out process and assisted with testing the water. The Free Press supplied a Pro-Lab Water Analysis Test Kit, purchased for $19.95 at the Great Lakes Ace Hardware store in Clawson. Among the contaminants it looked for were lead, coliform bacteria, pesticides and two forms of chlorine. It found none in measurable levels. Still, there evidently was enough chlorine taste and aroma to bother the Rasmussens, although a reporter couldn’t detect it. Giving the water several hours to sit in pitchers, however, allowed that residue of the treatment process to evaporate.

Opinion: Highland Park water debt is a minefield for Gov. Gretchen Whitmer

More: Grant aims to provide Flint moms, babies with cash payments to improve health

What it would take: Michigan lawmakers want to require water filters in every school

In these inflationary times, an easy way to save is taking bottled water off your shopping list. That assumes that your tap water is safe and appealing. It isn’t in much of the nation. In parts of Michigan, bottled water is essential where wells have been contaminated. But the water from GLWA, serving 4 million Michiganders, certainly qualifies. It’s so good that mega-marketers of bottled water buy it, said Bryan Peckinpaugh, spokesman for the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department. Detroit, along with dozens of cities and townships, buys tap water from GLWA.

Detroit's system “charges the Pepsi, Coca-Cola and Faygo bottling facilities for treated drinking water that they use in the manufacturing of their products,” Peckinpaugh said. Just as with residential customers, the companies “are billed for each CCF of water we provide,” he said. CCF stands for 100 cubic feet, where the “C” is the Roman numeral for 100.

Those bottlers, by the way, are fully paid up on their accounts, Peckinpaugh said. Before filling plastic containers with metro Detroit’s tap water, the big companies add a step. They run the water through filters that remove all natural minerals as well as traces of the chlorine used by the Great Lakes Water Authority for purification, according to their websites. After removing everything from the water, they're forced to put some things back, simply because water that is devoid of natural minerals not only tastes bad, it's bad for health. Then the bottlers mark up the price more than 100 times, taking 20 ounces from costing well under a cent at the tap to, typically, $1 or more a bottle at party stores.

The result? A waste of money, according to Consumer Reports magazine. As its investigators concluded, there's no health advantage to bottled water when tap water has been tested and found to be safe, they said. And, in time, particles of plastic from the containers can migrate into the contents, especially if bottled water is left in the sun, after which the consumer will be drinking micro-plastic particles — something not found in metro Detroit’s tap water.

“The hotter it gets, the more the stuff in plastic can move into food or drinking water,” says Rolf Halden, director of the Center for Environmental Health Engineering at Arizona State University’s Biodesign, quoted on the website of National Geographic magazine. (Another way to save on water? Consumer Reports' May/June issue lists washing machines that use less water than most.)

In Detroit’s Corktown area, Brew Detroit is an enthusiastic customer of GLWA’s water, according to Tim George, quality control director.

“I’m very passionate about water chemistry,” George said. Water from Detroit’s taps is “really good clear water for brewing,” he said. Brew Detroit is a contract brewery, “so we brew for other breweries across the country,” many of them located where the water isn’t ideal, George said.

“Here, you can drink it straight out of the tap with no problem,” he said. Michigan’s abundance of pure water is a reason why the Great Lakes State has the sixth most microbreweries in the nation, and fourth most among states with modest populations. So, does Brew Detroit run through the many "purification" steps cited on the websites of water produced by bottlers for Coca-Cola, Pepsi and Faygo?

"Not at all," George said. "That's all very expensive and the water here doesn't require that" for making excellent beer and ale, he said.

Last month, the Free Press toured Detroit’s original water treatment site, the Water Works Park plant, on East Jefferson about two-thirds of the way from downtown to Grosse Pointe Park, across from the Pewabic Pottery.

Although some buildings are more than a century old, their interiors have state-of-the-art technology, said tour guide Cheryl Porter, chief operating officer for water and field services at GLWA. Porter visits only occasionally but technicians are on duty 24/7, “monitoring all phases of our treatment process,” Porter said.

Of all the places in the world not to buy bottled water, metro Detroit is prime territory, she said. If more people in southeast Michigan learned to trust their tap water, not only would they save money but they'd also keep plastic bottles out of our streets and streams, as well as out of lakes and landfills, not to mention the sewers — another responsibility of GLWA, Porter said.

Tap-water drinkers can take a big swig this week to celebrate Drinking Water Week, which runs through Saturday. It's aimed at educating the public about water quality, according to the American Water Works Association, a Denver-based trade group of water purification professionals. Porter, who has degrees in chemistry and law, is the group’s president-elect for 2023-24.

In the kitchen of the Rasmussen home in Grosse Pointe Park, a very interested witness to the water testing was Karin Garrett, of Grosse Pointe.

"Isn't that a coincidence? I just happen to be reading about water. It's a book by Erin Brockovich," Garrett said. That book is "Superman's Not Coming: Our national water crisis and what we the people can do about it," written with journalist Suzanne Boothby.

Published in 2020, Brockovich — played by Julia Roberts in a 2000 movie, about her crusade to expose water pollution in California — tells of water worries nationwide. A prominent subject in her book is Michigan's serious pollution problem with groundwater, making well water undrinkable in some locations.

But the book doesn't say there's anything to worry about with metro Detroit's water, drawn from the Great Lakes. In fact, it never mentions it.

Contact Bill Laytner: blaitner@freepress.com

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Metro Detroit tap water helps residents, bottlers save money