Can Mexico turn around its environmental train wreck?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As dozens of scientists gathered in Switzerland last month to finalise a seminal United Nations report on the climate crisis, across the Atlantic, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador was gearing up for a celebration of all things oil.

On 18 March, he joined tens of thousands of people in the heart of Mexico City to mark the 85th Anniversary of nationalising the fossil fuel industry.

López Obrador, popularly known as Amlo, boasted how his administration had saved the national oil company, Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex), and said that Mexico would stop importing foreign oil in 2024.

"That the people of Mexico know that the electric and oil industry is being rescued, this is part of what inspires us,” he said.

It was quite the political spin. Pemex’s output has dwindled over the past decade, and the company’s balance sheet carries more debt than any other oil major at an astonishing $107.7bn, according to Bloomberg.

Reports of mismanagement and major industrial accidents have also been rife – no more dramatically visualised than in July 2021, when a Pemex undersea gas pipeline ruptured in the Gulf of Mexico and set the ocean on fire.

🚨 Sobre el incendio registrado en aguas del Golfo de México, en la Sonda de Campeche, a unos metros de la plataforma Ku-Charly (dentro del Activo Integral de Producción Ku Maloob Zaap)

Tres barcos han apoyado para sofocar las llamas pic.twitter.com/thIOl8PLQo— Manuel Lopez San Martin (@MLopezSanMartin) July 2, 2021

Yet regardless of Pemex’s vulnerabilities, the López Obrador administration has prioritised fossil fuel expansion in Mexico at the expense of clean, renewable energy.

The decision is symbollic of a broader shift away from once-ambitious climate and environmental goals in the country since Amlo, a folksy, left-wing populist, came to power in 2018.

He sailed to victory on promises of stamping out political corruption, ending the violent strangle-hold of drug cartels and improving the financial situation and social safety nets for a weary populace.

Under Amlo, Mexico has acquired an oil refinery in Houston, Texas, and is building another in the president’s home state of Tabasco – two projects which he dubbed “climate actions” at last year’s Major Economies Forum on Energy and Climate.

His government had decided to ignore “the siren calls ... that the oil era was over,” Amlo quipped, when the Tabasco project was announced.

Meanwhile, Mexico’s solar and wind development has stalled – despite the country’s abundant sunshine and high desert plains – in favor of the state-owned, fossil-fuel heavy Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) and Pemex.

‘Critically insufficient’

The moves are part of the reason that Mexico is now one of the least ambitious countries when it comes to tackling climate change, with national efforts deemed “critically insufficient” by Climate Action Tracker (CAT), an independent group which analyzes international action.

Mexico’s latest 2030 target to cut carbon emissions is weaker than the goal set in 2016, giving it the uneviable title of Latin America’s largest emitter per capita.

“If all countries were to follow Mexico’s approach, warming could reach over 3 [degrees Celsius] and up to 4C,” CAT warned.

Along with the rest of the world, Mexico promised to cut emissions to avert dangerous temperature rise when it signed the 2015 Paris Agreement. Scientists say that beyond the Paris goal of 1.5C, climate impacts will become more severe and unpredictable.

And there are even doubts over how Mexico will achieve its modest emissions-reduction target, Gustavo Ampugnani, executive director of Greenpeace Mexico, told The Independent.

“We recognise that [the López Obrador administration] has some very positive projects, like the solar [development] in Sonora, but still this is not enough,” Mr Ampugnani said.

“The whole narrative of this government is to leverage the development model on fossil fuels, and this is something that Greenpeace wants to see change in all countries including Mexico.”

It wasn’t always this way. A decade ago, Mexico was a beacon of progress as the first developing country to pass comprehensive climate change legislation, cut fossil fuel industry subsidies and ramp up environmental protections.

While López Obrador does not deny climate change, environmentalists say his personal agenda trumps Mexico’s most pressing environmental and climate concerns.

“He doesn’t talk a lot about science, but he’s not a denier of climate change,” Mr Ampugnani said. “But that doesn’t exclude the fact that climate change is not high on his agenda, maybe because he’s more romantic or nostalgic.”

Yet he has vilified scientists and environmentalists, a particularly troubling move considering Mexico is repeatedly named as one of the deadliest countries in the world for activists and land defenders.

He lashed out at environmental groups who have opposed the contentious Tren Maya, his pet infrastructure project, as “foreign agents”.

The Mexican Center for Environmental Law said that he was “criminalising” environmentalists.

“We demand a public apology for the attacks and defamation we have been subjected to by the president,” the group tweeted. “International development aid is legal, as are donations from private people, companies and Mexican foreign foundations.”

The ‘triggering’ train

The Tren Maya, or Maya Train, project in the Yucatan Peninsula has been riddled with controversy since the beginning.

The peninsula is home to the Sian Ka’an biosphere, one of Mexico’s largest protected areas, which teems with tropical forests, mangroves, marshes, barrier reef and more than 300 species of bird and thousands of other animals.

The new bio-diesel train, running on a 950-mile loop, will link the resorts of Cancun, Playa del Carmen and Tulum with remote areas. The aim is to get tourists off the beach and out to archaeological sites, without adding carbon-intense flights and road trips.

Amlo promised that “not a single tree” would be sacrificed in building the train, when he was a presidential candidate, and the Mexican government called the project a “trigger” for sustainable development, particularly for marginalized and poor communities of Indigenous Mayans who the train is named after.

The reality has shaped up quite differently.

Firstly, those trees: just one section of Maya Train track slices through 68 miles of rainforest, and the government tourist agency, FONATUR, concedes that 3.4 million trees have been chopped down. (Some environmentalists say it’s closer to 9 million trees.)

The train, which includes restaurant cars and sleeping cabins, will thunder over the region’s vast underground network of caves, called cenotes, which supply freshwater to five million people.

The limestone cave roofs are only a few inches thick in places so structural supports will need to be driven through them – a major threat to the water supply, environmentalists say.

El impulso al turismo con el Tren Maya será de primera, también con la mejor conectividad y abasto de servicios que generan empleo y bienestar 🇲🇽

¡Vamos! #SúbeteAlTren 🚉 pic.twitter.com/EfgBUhKrRI— Tren Maya (@TrenMayaMX) April 17, 2023

The Yucatan Peninsula, like many other regions in Mexico, can little afford more stress to its supply. Water availability has been reduced by nearly two-thirds in the region in the past two decades, according to Mexico’s national water board.

And there are serious concerns about the risks posed to the Mayan people.

In December, the United Nations Human Rights Council issued a warning that the Maya Train "endangers the rights of indigenous peoples and other communities to land and natural resources, cultural rights, and the right to a healthy and sustainable environment”.

José Clemente May, a member of the Mayan community in the city of Homún, told The Independent that the president “promises one thing and does another” and that he is simply focused on getting his party re-elected next year.

He pointed out that towns and cities on the Yucatan Peninsula already lacked of water and decent medical services.

“With the construction of the Tren Maya, there will be great growth close to the stations and even the appearance of new cities or towns,” he said. Mr Clemente May was also concerned that more people and economic demand would attract criminals to “besiege” the area as drug cartels have done in neighboring Cancun.

And the very legality of the project, which is expected to cost up to $20bn, is in doubt: President López Obrador had elevated the Maya Train to a national security project in order to bypass a legal requirement for an environmental impact assessment.

“AMLO doesn’t care about the impacts to the environment. He wants [the train] because he wants it. He instructed his people and they started to build it,” Alex Olivera, senior Mexico representative at the conservation nonprofit, Center for Biological Diversity (CBD), told The Independent. His group and other organisations are suing the Mexican government over the train.

“It’s just one man’s idea, which he thinks is good, without having any previous environmental or economic assessment as to what’s the best option for the area to activate the economy,” he added. “And it’s causing destruction in the Mayan forest.”

The López Obrador administration claims that an Environmental Impact Statement has been carried out for the train. However there have been no geological and geohydrological studies to rule out collapses in the rail line, according to a report in the newspaper El Economista.

The Independent has contacted the López Obrador administration for comment on this article.

Changing tides

And while meaningful climate progress wanes, increasingly severe cycles of storms, drought and extreme heat beat down on Mexico’s mega-cities, coastal towns and rural villages alike.

A heavy toll is being paid across the Mexican economy including in critical areas like tourism and farming. Some 80 per cent of weather-related financial losses in Mexico have affected the agricultural sector in the past 30 years, according to the US International Development Agency (USAID).

Hurricanes have become more powerful in the Gulf of Mexico over the past half century, too. Hurricane Wilma, in 2005, left behind $1.8bn in damages in Cancun. This past September torrential downpours led to devastating flooding and landslides in several states, and caused at least one death.

On the flipside is a historic water shortage across many areas. The city of Monterrey, the bustling capital of the north-eastern state of Nuevo León, was forced to place 1 million people under water rationing last July.

Dry conditions are exacerbating wildfire outbreaks. In Mexico City alone, at least 66 fires were reported in 2019, with another 130 in the surrounding region.

The fires add to air pollution already spiking due to industrial growth and a boom in diesel and petrol-run vehicles. Polluted air kills 17,000 people every year in Mexico including 1,680 children under five, according to global air monitoring firm IQ Air.

But Amlo has rooted his political success in Mexicans more immediate, and valid, worries about violence, corruption,and the economy. At the Mexico City rally last month, widely seen as the unofficial kick-off for the 2024 presidential elections, López Obrador boasted of his anti-corruption battle and said that government cost-cutting had boosted state pension and welfare programmes.

He even claimed that federal crimes had been reduced by a third; kidnapping by 76 per cent; and femicides by 28 per cent. (The Independent has been unable to verify these figures).

On the climate crisis and environmental pollution, he was silent.

But with the upcoming elections, a window of opportunity has appeared. López Obrador has confirmed he will not run for office again, and has promised to completely withdraw from Mexican politics when his term ends in September 2024.

It’s yet unclear who will be the candidate for his party, Morena, which remains the strong favourite among Mexican voters. Recent polling revealed that if the elections were today, some 45 per cent of the electorate would vote for them.

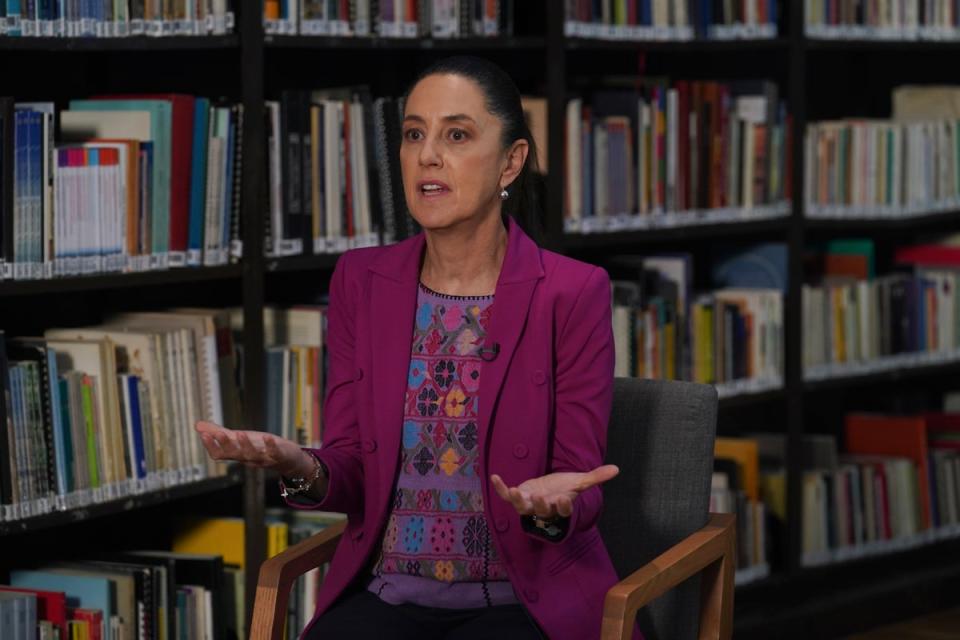

A handful of names have emerged as front-runners: Marcelo Ebrard, Mexico’s Secretary of Foreign Relations; Claudia Sheinbaum, the Mayor of Mexico City; Adán Augusto López, Secretary of the Interior; and Ricardo Monreal, a senator.

Sheinbaum is comfortably leading that pack, recent polling found. She holds similar leftist ideals as the current president, and recently toldThe Associated Press that the neoliberal economic policies of Mexico’s past leaders were to blame for exacerbating inequities. López Obrador holds her in high regard, describing her as a “hard-working, honest woman with convictions”.

But they diverge on what priority the climate crisis should take on Mexico’s to-do list.

Sheinbaum is a world-renowned environmental scientist and part of the UN climate science panel, the IPCC, which won the Nobel Peace Prize for its work in 2007.

As Mayor of Mexico City, she has introduced sweeping environmental and climate plans including tree planting, tackling river pollution, managing water shortages, recycling initiatives, air quality monitoring and solar power installation.

Such has been her progress that she was invited to speak about her climate vision during President Biden’s Leaders’ Summit on Climate to mark his first Earth Day in the White House.

“We are convinced that in order to reduce the catastrophic effect of climate change, we need a different approach,” she said.

“Education, healthcare and a healthy environment are people’s rights, not privileges.”