Miami-Dade cities will lose money due to COVID-19. They can only guess how much

Miami-Dade County may be inching toward reopening its economy, but no one knows when it will return to any semblance of normalcy. For the local officials overseeing municipal budgets, that’s a tricky place to be: There will surely be revenue shortfalls, many say, but it’s almost impossible to predict just how much will be lost.

For now, the best they can do is take an educated guess. Some local governments have already made painful decisions, laying off or furloughing workers and freezing spending. Others are holding their breath and waiting before cutting staff and services.

But the prospects aren’t pretty. On Monday, the financial services company Moody’s downgraded its national outlook for local governments from “stable” to “negative,” citing a growing expectation that the economic recovery process from COVID-19 will be slow.

Cities still have a few months to go before budget season, and most of their property tax revenues have already been collected for this fiscal year. But local governments should try to get ahead of the problem, said Lenny Jones, a managing director at Moody’s — even though they don’t know what the future holds.

“Good management teams are saying, ‘We don’t know when this is gonna end, but we need to be prepared,’” Jones said. “They’re thinking about those things now and are putting things in place now.”

City officials in South Florida are no strangers to unforeseen economic crises. After Hurricane Irma, costs for debris cleanup blew holes through some municipal budgets, and then left many waiting months or even years to get reimbursed by the federal government.

But the COVID-19 pandemic is unlike anything local governments have seen before.

“Hurricanes are enemies you can see,” said Otis Wallace, the mayor of Florida City in South Dade. “Coronavirus is a more nebulous kind of crisis. I find it more stressful.”

Over the past few weeks, city officials have done their best to project the budgetary hit that’s coming. Cities that depend on tourism, like Miami Beach, have been hit the hardest so far. Miami Beach City Manager Jimmy Morales has already furloughed 35 full-time employees, released 258 part-time workers, and put a freeze on hiring, saving the city $17.5 million.

Assuming three months of slow economic activity, Miami Beach stands to lose between $65 million and $105 million, John Woodruff, the city’s chief financial officer, said in a presentation in April, including up to $35 million in resort taxes through September.

Across the county, officials hope healthy reserve funds will help keep future cuts to a minimum. Jones, the Moody’s analyst, said communities that rely more heavily on revenues that fluctuate, like hotel occupancy and car rentals, typically keep more in reserves.

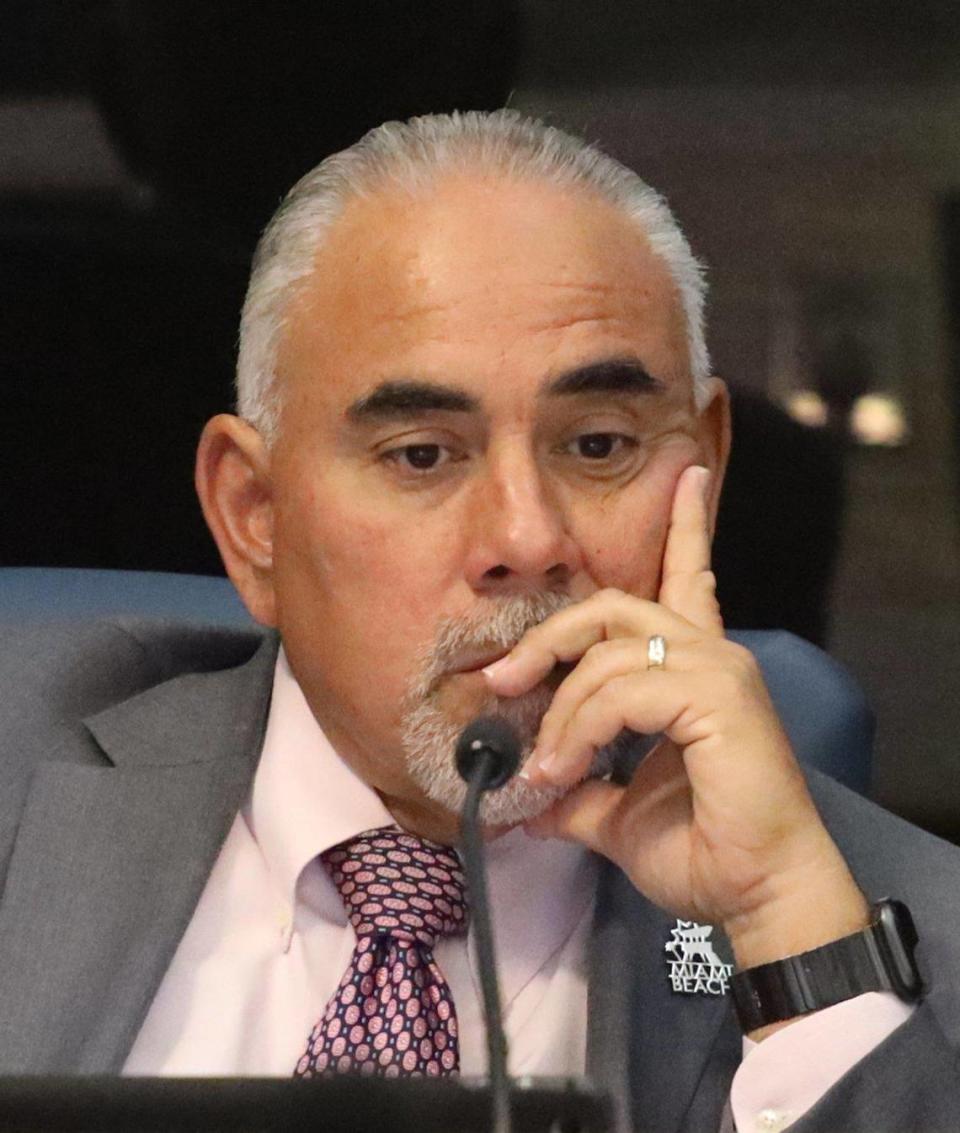

“The reason we have a rainy day fund is for precisely moments like this,” said Miami Beach Mayor Dan Gelber, who noted that the city tucked away a $16 million budget surplus in its reserves in 2019. “It’s so you don’t have to reduce essential or critical services like fire and police, so you don’t have to dramatically change your quality of life.”

At the county level, Miami-Dade saw its hotel tax revenue plunge 62% in March, while a county sales tax on restaurants — which helps fund programs for homeless residents and domestic violence victims — fell 57%.

Tourist taxes are also a concern in the small beach town of Surfside, which is slowing its spending because of hotel-related losses. Town Manager Guillermo Olmedillo said the town, which has a budget of around $30 million, could see revenue drops between $800,000 and $1.2 million this fiscal year if the crisis lasts through June, primarily due to lost resort taxes.

After seeing an uptick in resort tax revenues in 2019 thanks to several new hotels, Surfside has now frozen all spending of that money, which goes toward running the town’s community center and promoting Surfside as a tourist destination.

“The length of the crisis is the biggest hurdle in determining the financial impact,” Olmedillo said.

The city of Miami, meanwhile, with a $1 billion operating budget, doesn’t have tourist taxes in its budget, softening the economic blow somewhat. But officials are still forecasting a $19.7 million shortfall, according to projections that assume a citywide curfew and stay-at-home order will be in place for another two months.

City Manager Art Noriega has already told Miami’s mayor and commissioners to prepare to cut their budgets, and city departments are also being asked to identify places to trim.

Bedroom communities brace for impact

The effects of the pandemic haven’t been felt to the same extent in bedroom communities around Miami-Dade where tourism is less of a factor. But shortfalls are still coming.

Take Coral Gables, for example, which is projecting an almost $10 million budget hole this fiscal year. The city expects to lose $4 million from parking receipts alone from mid-March to mid-July, plus another $1 million in revenue from the county’s half-penny sales tax.

The city has implemented a freeze on spending and new hires to offset $7.4 million in expected losses.

In the longer term, local officials also fear that residential and commercial property values will decrease in a post-pandemic world, shrinking cities’ tax bases. Those effects won’t be known until 2021 after new property assessments come in.

“That can put a hole in our revenue, for sure,” said Coral Gables City Commissioner Michael Mena.

In North Miami, the city indefinitely furloughed about 140 part-time employees — meaning they aren’t working or being paid — about three weeks after declaring a state of emergency in mid-March. The decision was made in part because the city isn’t getting any revenues for its rental facilities and parks, said Arthur Sorey, interim city manager.

But the potential for lost taxes down the road due to decreased property values also played into the decision, Sorey said. Councilman Scott Galvin pointed out that many North Miami residents work in hospitality and have lost their jobs, limiting their ability to pay rent and mortgages.

“Everyone anticipates property values dropping in the next cycle,” Sorey said. “I think all cities are really bracing for the next two years to see what the ultimate fallout is gonna be.”

In Miami Gardens, meanwhile, officials are already thinking about how COVID-19 might affect their biggest property taxpayer: Hard Rock Stadium, whose taxable value is based in part on the events that are held there — many of which have already been canceled for 2020.

“There will probably be a decrease in valuation of the stadium just based on what they’ve gone through this year,” Mayor Oliver Gilbert said.

The short-term effects in Miami Gardens, like in other bedroom communities, appear limited. In Homestead, for example, about 90% of property taxes have already been collected for this fiscal year, Mayor Steve Losner said, accounting for the bulk of the city’s $50 million budget.

And in South Miami, a city of 13,000 people with a $21 million annual budget, City Manager Steve Alexander said he made a priority of creating a $7 million reserve fund and has no plans to lay off or furlough any of the city’s 150 employees.

“We can hold our breath for 26 months if we have to,” he said.

How much federal help is coming?

What happens to city budgets in the coming months will depend in part on what the federal government is willing to provide. Under the CARES Act, the massive stimulus package passed by Congress in response to COVID-19, cities of under 500,000 people can’t apply to receive money directly. The funds are instead distributed at the county level.

That means even cities as big as Miami, whose population is around 470,000, could get left out.

In an April 16 letter, the National League of Cities, National Association of Counties and U.S. Conference of Mayors called on Congress to provide $250 billion in “robust, dedicated, and flexible funding” to be distributed among every municipal government in the country.

“Both counties and cities are expending an unprecedented amount of resources while losing historic amounts of revenue,” the groups wrote. “All local governments, regardless of population, urgently need direct federal funding to help us continue to fight COVID-19 and protect our residents through the summer and beyond.”

Adding to the uncertainty: cities have no idea when their emergency spending on items like protective equipment for employees and COVID-19 testing kits will get reimbursed by the federal government, if it’s reimbursed at all.

“When hurricanes happen, everyone is used to the drill and there are formulas for cities to get FEMA aid,” said Alexander, the South Miami city manager. “But with CARES, cities have to go through the county to get money. We are all enforcing county and state executive orders restricting what people and businesses can do, so we ought to get some compensation.”

During a virtual town hall meeting Tuesday, U.S. Rep. Donna Shalala, who represents a large swath of Miami-Dade County, said she and her fellow Democrats are working on legislation that “will bring the money directly back to cities” to pay for services like police and fire.

“I’ll go to Washington next week and hopefully not come back without money for Mayor Gelber and all the other cities,” Shalala said during the meeting, which was co-hosted by Gelber. “We need to make that investment.”

Miami Herald staff writers Douglas Hanks, Joey Flechas, Linda Robertson and Martin Vassolo contributed to this report.