Miami-Dade uproots sex offender camp yet again. Does harsh law really make public safer?

The latest eviction order came earlier this month: Some 70 paroled child sex offenders, now living in a flimsy village of tents, cardboard boxes and rusty campers in an industrial zone just east of Miami International Airport, were told they had to find a new home — yet again.

Miami-Dade County’s Health Department posted signs giving them until Dec. 5 to leave, citing illegal camping and unsanitary conditions. Because most South Florida counties and cities have laws designed to keep them far from children, the options for moving are few and far between — especially when most of them don’t have the money or means to move into permanent housing.

In the past few years, similar encampments of convicted sex offenders under harsh residency restrictions have been forced from sites under a bridge at the Julia Tuttle Causeway, off of Northeast 79th Street near another overpass and out of an Allapattah trailer park. They’ve also been tossed from a warehouse district in Hialeah near train tracks and from another industrial section of Miami-Dade not far from the old Miami Jai-Alai Fronton.

“It’s like a game of Whack-A-Mole,” said Pastor Frank Diaz, who visits several camps around Miami-Dade each week to feed, listen to and pray with a group most people disdain as social pariahs. “If they’re gone,” he said, “who cares?”

The forced nomadic existence doesn’t just make life difficult for sex offenders, it creates a host of challenges for law enforcement agencies charged with keeping track of them. And those problems also raise questions about the accuracy and effectiveness of the Florida Department of Law Enforcement’s sex offender registry, an online list that was touted to inform the public about potential risks from sex predators.

Numerous studies over the past two decades suggest the harsh living restrictions and registries have not been effective. A 2015 study of adult sexual offender management by the U.S. Department of Justice concluded that despite broad public support, residency restrictions may do more harm than good.

“Finally, the evidence is fairly clear that residence restrictions are not effective,” the report noted. “In fact, the research suggests that residence restrictions may actually increase offender risk by undermining offender stability and the ability of the offender to obtain housing, work, and family support. There is nothing to suggest this policy should be used at this time.”

Jill Levenson, a Barry University professor of social work, who conducted a similar study the same year, reached virtually the same conclusion. Using data compiled between 1990 and 2010, her study found that the 6.5 percent re-arrest rate for sexual offenders was well below that of repeat offenders of other major crimes. Her study concluded that residency restrictions are actually more likely to increase the number of times convicted offenders repeat a sex crime.

“There are a million different kinds of ways someone can commit a sex offense. It doesn’t mean it will continue. They’re not all really high-risk and not all really prone to re-offend. Evidence shows that resident restrictions have never been shown to protect kids,” she said. “There’s a lot of fear and anger and that’s all understandable. But when you legislate people into homelessness, it doesn’t really make sense. Why does anybody think that making them homeless is going to make people safer?”

Hundreds of missing sex offenders

Then there’s the problem that police lose track of hundreds of sex offenders every month. FDLE records show that, as of November, Florida had about 44,000 people registered as sex offenders required to check in monthly with local law enforcement agencies. During most months, records show, Florida doesn’t know where close to 1,000 of them actually are and many others have registered addresses that are suspect — last summer, a group of as many as 110 convicted child sex offenders listed the location of a McDonald’s and a Chick-fil-A in Fort Lauderdale as their place of residence.

In Miami-Dade, which has one of the largest registries in the state, 262 sex offenders were unaccounted for as of November, according to the latest figures available. Broward County deputies lost track of 72 convicted sex offenders over the same time period. In Central Florida’s Orange County, 71 people convicted of having sex with minors were unaccounted for and 23 others couldn’t be found in Palm Beach County.

Miami-Dade police have a couple of squads tasked with keeping track of sexual offenders and Lt. Luis Poveda said the vast majority of registered offenders cooperate and update the department of their whereabouts on schedule. The number of registrants fluctuates with some dying or moving or being deported or sent back to prison, he said, but has remained relatively stable the past few years.

“We keep track. We have the tools,” said Poveda. “Compliance on their end is pretty high [because most don’t want to go back to jail]. But as they move from one area to another, it’s a concern.”

Still, “absconded” or “transient” offenders are common enough that over the last few years, Miami-Dade police have published a periodic leaflet in the Miami Herald with names and mug shots of dozens of sex offenders who have gone missing. The online registry also lists many names of offenders whose whereabouts are unknown.

Exactly how many of the offenders in Florida committed sex crimes against children and face residency restrictions isn’t clear. The state database doesn’t break it down that far, only recording convicted sex offenders.

FDLE’s registry can be searched by offender name but also by ZIP code and address, which produces a list of nearby sex offenders. One northeastern section of the city of Miami, for instance, shows 40 pedophiles living within a half mile of Northeast 79th Street in and around 10th Avenue, mostly clustered in a few apartments. But a dozen of them are listed as transients with addresses on street corners. And that’s the group that is continually uprooted.

FDLE Spokeswoman Gretl Plessinger said the state’s sex offender registry is only as accurate as the numbers fed to it from each Florida county. “They’re entered in at the county level and then automatically transferred to the registry,” she said.

Critics point to expansive off-limits zones as the biggest problem in tracking the state’s population of paroled child sex offenders.

State law demands that convicted sex offenders live at least 1,000 feet from a school or any place children might gather. But some counties, like Miami-Dade, in the national spotlight a decade ago for the bizarre spectacle of dozens of offenders staking a claim to a waterfront colony under a Biscayne Bay causeway, went much farther: convicted child sex offenders can’t live within 2,500 feet of a school or a place where children gather.

That means, according to critics of the sex offender laws, that if you exclude the county’s western wooded area or The Redland, offenders can only live in less than one-half of one percent of all the property in Miami-Dade County. Several years ago — as a result of campers filling the grassy areas of County Hall during the Occupy Wall Street era — it got even tougher to find a place to live after Miami-Dade County commissioners passed ordinances allowing cops to remove offenders for illegal camping or unsanitary conditions.

The county health department is using that expanded authority to break up the latest encampment in an industrial district consisting mainly of warehouses and junkyards, which otherwise adhered to Miami-Dade’s 2,500-foot ordinance. Health workers visited and erected a sign saying the group was camping illegally and had to leave.

‘I’m not going to kill’

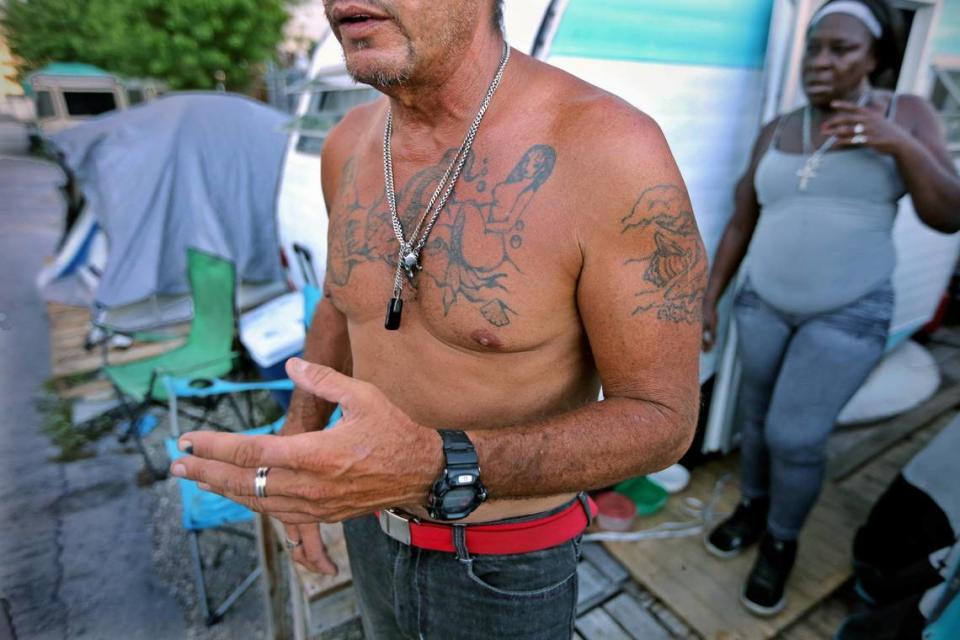

Roberto Garcia, who lived in a man-made trailer on the rodent-infested lot at the corner of Northwest 36th Avenue and 48th Street since the summer, said the rules make it almost impossible for him find work or a safe place to live.

He described himself as a sick person needing treatment, not a predator looking for victims. He said he was convicted of sexually battering his girlfriend’s daughter in 2008, who was under 12 years old at the time. He agreed to a plea deal that allowed him to remain out of prison and on probation for over a decade. But Garcia was imprisoned by 2014, he said, because he didn’t realize the battery had run out on his GPS monitor until his probation officer showed up.

“I’m not going to kill. I’m not going to steal and I’m not going to sell drugs for it,” he said, one day this month as the sky grew dark and thunderclaps exploded above him. “It’s a mental cancer.”

Critics also say many loopholes undermine boundary laws as a deterrent for predators. In many South Florida cities, for instance, convicted child sex offenders can legally spend daytime hours at their homes in neighborhoods, possibly near schools or parks, but then are forced by law to drive to homeless camps where they sleep in vehicles over night to meet a curfew requirement for an official living address.

“That doesn’t make any sense,” said Jeffrey Hearne, an attorney with Legal Services of Greater Miami who with the ACLU of Florida filed an appeal in September to end Miami-Dade’s 2,500-foot ordinance. “You can live next door to a home full of children?”

Hearne estimates there are about 1,400 child sex offenders on parole in Miami-Dade. He said two of the four plaintiffs in the lawsuit, who had endured harsh living conditions to comply with the law, had died in the past few months.

“It’s sad and unfortunate, but people are living in the streets and that happens,” he said.

Some cities have eased restrictions. Last summer, Fort Lauderdale commissioners relaxed living requirements for sex offenders after hearing that only 1.4 percent of the city was technically legal — an off-limits boundary so harsh, the Sun-Sentinel reported in June, that the city’s own attorney said it likely would not stand up in court. Commissioners also learned that many predators posted suspect addresses in a narrow “legal” strip along Federal Highway — fast food restaurants and a Target parking lot.

Though they still can’t sleep within 1,400 feet of where children gather, the commission decided that bus stops no longer count as a child gathering spot. That upped the percentage of land in the city where sex offenders can sleep from 1.4 percent to more than 15 percent.

Activists hailed that move as a “phenomenal step.”

A national movement

The national movement to inform the public about sex offenders began decades ago with the kidnapping at gunpoint and disappearance of a 11-year-old child in Minnesota named Jacob Wetterling. By 1994, Congress passed the Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sexually Violent Offender Registration Act, the first bill that would create a national registry for sex offenders.

Two years later, Megan Kanka, 7, was raped and murdered in New Jersey by a neighbor with a previous conviction for sex assault on a child. This time Congress went even further, passing Megan’s Law, which forces convicted sex offenders to register with local law enforcement.

Both those bills, however, would be replaced a decade later in 2006 with the Adam Walsh Child Protection Safety Act, which created a national sex offender registry required to be updated every three months. States were forced to comply or risk losing federal monies intended for local law enforcement.

Walsh, a gap-toothed 6-year-old was abducted from a Hollywood, Florida mall in 1981 after his mother lost sight of him, his severed head found two weeks later in a canal about 100 miles north in Port St. Lucie. The child’s saga turned into a movie and later his father would become famous after hosting a show called America’s Most Wanted for more than two decades.

But even before the Walsh bill became law, a movement was underway in Florida that would make it extremely difficult for those convicted of sexually offending a child to find a place to live. It began in 2001, when Ron Book, one of the state’s most powerful lobbyists, learned his daughter had been physically molested and mentally abused by her nanny for half a decade.

Book went on a legislative offensive against sexual predators that still resonates today.

By 2005, both Miami Beach and Miami-Dade had passed laws restricting convicted child sex offenders on parole from living within 2,500 feet of schools or anywhere children gather. The rule was so restrictive that virtually all of the Beach and Miami-Dade became out-of-bounds. Dozens of states and about 200 cities in Florida would follow suit with similar restrictive living ordinances.

In 2009, a bridge on Miami’s Julia Tuttle Causeway put a national spotlight on the grim consequences of the law: More than 70 sex offenders built a pariah village with makeshift tents of torn cloth and cardboard under the span, claiming they had no other place to live.

Eventually, amid outrage and debate, the sex offender colony moved. They first formed a small encampment in the Shorecrest community, at the corner of Northeast 79th Street and 10th Avenue, but were forced out when Miami Commissioner Marc Sarnoff ordered a tiny public park nearby — throwing them in violation of the 2,500-foot rule. It’s been hopscotch ever since, with sex offenders settling in, then sent packing.

The next destination, for now at least, is uncertain.

Despite lawsuits and pressure from homeless and civil liberties advocates to soften the rules, Book, for one, remains unmoved and believes the residency rules and registry protect the public.

There are some studies that support Book’s advocacy of tough treatment, though they are few. Last year, a study of 400,000 prisoners by the Arizona Voice for Crime Victims found that 17 percent of convicted sex offenders re-offend within five years and that the number rises to 21 percent over a 10-year period.

“I’ve not changed my mind on any of those things. They’re against everything I and my daughter did,” said Book. “Pedophiles don’t set policy. All they [and their advocates] want to do is stir it up.”

Book said he refuses to help change “good public policy” for a small minority of people. He said most local pedophiles have found housing with the help of the Miami-Dade Homeless Trust, which he oversees. The state database also shows clusters of convicted child sex offenders living in apartments like the ones in northeast Miami.

Book did say the trust is now working on a potential residential setting for the sex offenders “that has potential.” He wouldn’t elaborate, saying after some vetting an announcement could be made in five or six months.

Diaz, the pastor who works with the sex offender camps, said politicians must find an answer to the relentless cycle of uprooting and forced homelessness — especially since decades of data argue the policies have not been effective.

“When they go to the bathroom there are no available toilets. When it rains, some places here break down,” he said. “They’re really broken. They feel like no one takes care or listens to them. They all have the scarlet letter.”

Miami Herald Staff Writer Ben Conarck contributed to this story.