Miami homeowner hopes to stop city from bulldozing home for something previous owner did

The gods seemingly don’t want Zarahy Pacheco, 41, to save her Miami home from the bulldozer.

For more than three years, Pacheco has fought to correct code problems that have resulted in “stop work” and “repair or demolish” orders on her home on Northwest 18th Street.

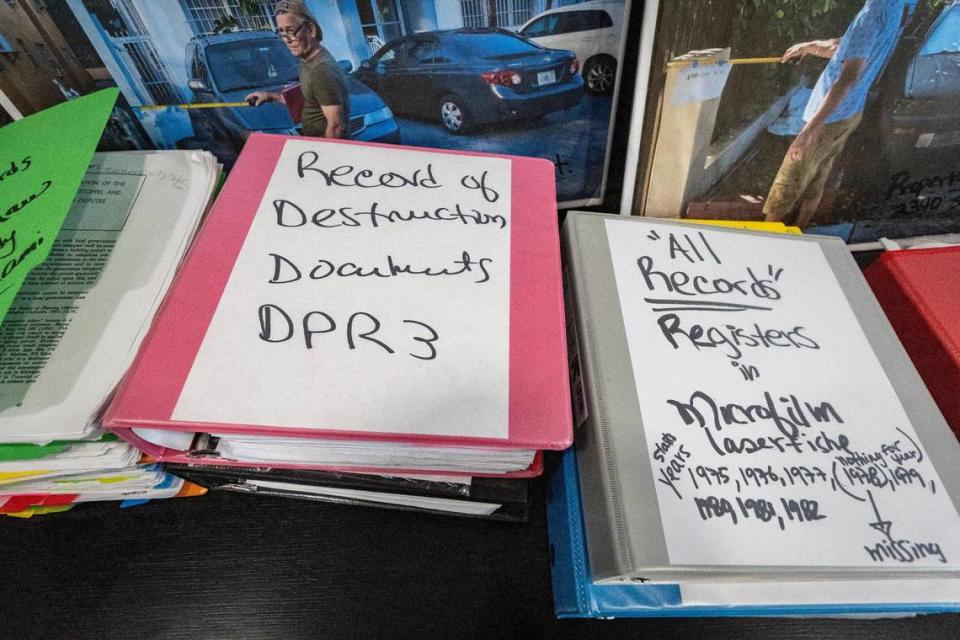

The paperwork documenting her struggle, sheathed in plastic like a parent’s scrapbook celebrating a child’s achievements, fills several binders.

The problems predate her purchase of the house nearly 20 years ago.

She has bounced between county and city offices, pored over microfilm records, hired a contractor and advanced him money only to have the contractor (and his wife) die of COVID during the pandemic.

Like a lot of governments, the city of Miami was harder to get face-to-face service from during the pandemic.

Since then, however, she has haunted the hallways of Miami City Hall, seeking audiences with the chief of zoning, the building department and various elected officials. She tried to interest Mayor Francis Suarez in her case, only to lose track of him when he went off to Iowa to run unsuccessfully for president.

She lined up the support of Commissioner Alex Díaz de la Portilla — whose chief of staff admonished her for speaking to the press — only to see him indicted on unrelated corruption charges and suspended from office.

At one point the city estimated it would cost $6,573,750 to bring her home — which actually seems quite nice — up to code. Permits fees are affected by the scope and cost of the project. It was an obvious mistake but took a while to rectify.

To assist with the overall effort, she hired a “permit runner,” someone who helps with getting permits, paying him $11,000 — which would have cost more, except for the $1,500 cash discount.

After one particularly excruciating encounter in September 2022 in front of the city’s unsafe structures board, Pacheco ended up in a restroom, sobbing.

Now, finally, this week, the commission may — she’s crossing her fingers — take up an ordinance that could help her out. Commissioner Manolo Reyes has promised to bring the matter forward.

“It has caused me years of stress.” Pacheco said.

Pacheco’s troubles can be traced back to Jan. 16, 2020.

That was when, as she recalls it, a city inspector wandered by as her father was working on the stucco. The inspector asked whether a permit had been pulled for the work. He said yes. Alas, the permit was for the roof, a separate project.

Pacheco says she mistakenly believed that the permit she had acquired was a master permit allowing her to make other repairs. Not so.

The inspector left, only to return later with a “stop work” order.

In the course of trying to correct that problem, she was informed of a much more ominous situation.

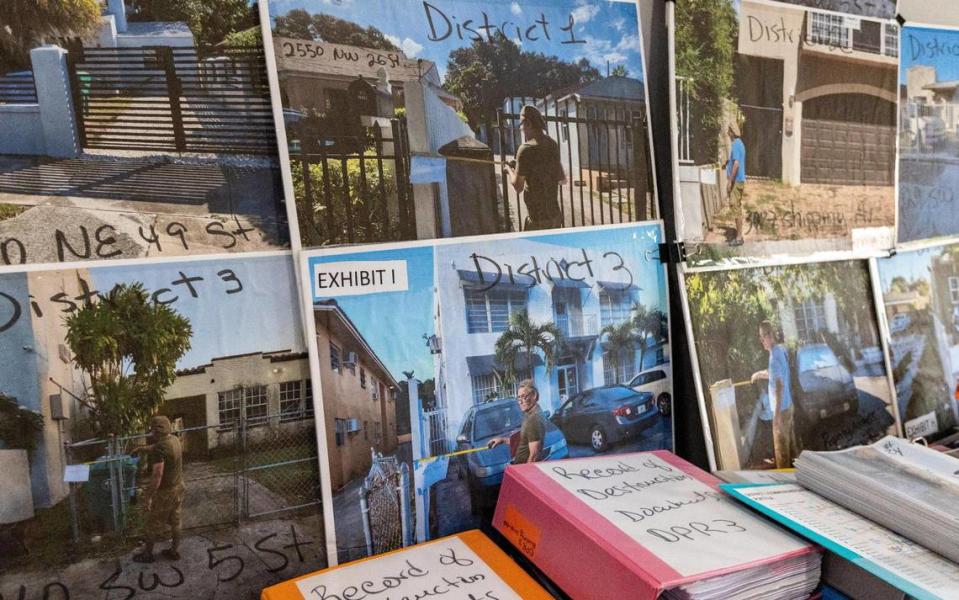

An addition to the house — one made long before she bought it in 2005 — violated the city’s setback rule, the requirement that said there must be a five-foot buffer between her structure and the neighbors’ property line.

She’s been fighting the city ever since, including pointing out there are plenty of other properties in the city that seem to have similar setback issues.

Lost permits, lost in bureaucracy

At some point, around when they corrected the $6 million estimate, her survey and plans had expired so she needed to submit updated documents to the unsafe structures people for them to remove the hold on her property so she could move forward.

She says a meeting did not go as expected. An official said it had been discovered that there was no permit on file for construction of her garage and deemed it an illegal structure.

Pacheco had to dig up a record from the county showing the garage was on the property since 1983 and was included in her tax bill.

She was told that wasn’t sufficient and to legalize the structure or demolish it.

She went back to the county, which contacted the city, which conceded she could keep her garage.

But there was still the matter of the setback. Pacheco missed many days from work trying unsuccessfully to retrieve her property records from the city’s microfilm archive. Eventually, she quit her job as an insurance auditor to focus exclusively on saving the house.

On Sept. 9, 2022, Pacheco appeared before the unsafe structures panel at ready to plead her case.

Every Friday morning at 9, the panel decides the fate of the properties on the day’s docket — sometimes ordering the demolition of those deemed unsafe. It’s no joke. City records show that Miami has ordered the demolition of 860 properties in the past five years. Of those, 153 were residential.

Pacheco said she came to the hearing prepared to present her exhibits, including a deed, survey plans and copies of email correspondence with city officials. But she was not allowed to make her presentation when it was pointed out that there were two names on the deed. The other was Pacheco’s mother.

A city lawyer said it appeared on the “quit claim deed” that Pacheco had transferred the house to her mother. Pacheco argued that she hadn’t, that she had simply added her mother’s name to the title, according to the meeting transcript. A board member suggested that she get her mom to sign a power of attorney.

The discussion lasted a while and Pacheco asked if she could just present her case.

A board member said no, according to the transcript, noting “we’re already burning a lot of daylight with this conversation as it is.”

The panel rescheduled her hearing for the following week.

Although the city had since acknowledged she was indeed the property owner, things did not go much better for Pacheco overall at the next hearing.

A member of the panel asked why she seemingly ignored a “stop work“ order. Pacheco tried to explain that she did not ignore the order but was unable to obtain permits because the city mistakenly charged her an upfront fee of over $30,000, based on the inflated $6 million+ estimate. But she couldn’t convince the board.

That’s the hearing that sent her to the restroom in tears.

“The issue is that during the pertinent time, even before Ms. Pacheco’s ownership, the setback by code was five feet and we have no permits on file evidencing the addition,” said Kenia Fallat, the city’s director of communications. “That means that the addition that brought the structure within 2.5 feet of the side lot line was likely performed unlawfully.”

Sometimes a city will “grandfather in” — effectively legalize — something that violates the current code, especially if it was done by a prior owner. But Fallat said that “only occurs when something was done lawfully under a prior code and subsequent change in the law makes it so one could not do that thing again.”

After the arrest of Díaz de la Portilla, Commissioner Reyes finally agreed to sponsor an ordinance that would address her problem.

If adopted, it would create a short-term amnesty pilot program designed to grant relief to homeowners with setback issues like Pacheco’s. If the structure does not meet the five-foot setback requirement but causes no detriment to the neighborhood, the zoning director would have discretion to grant a variance.

If that actually happens, it could be good for Pacheco’s health as well as her wealth. On Sept. 18, she ended up hospitalized with chest pains. Her doctors told her to try to limit her stress.