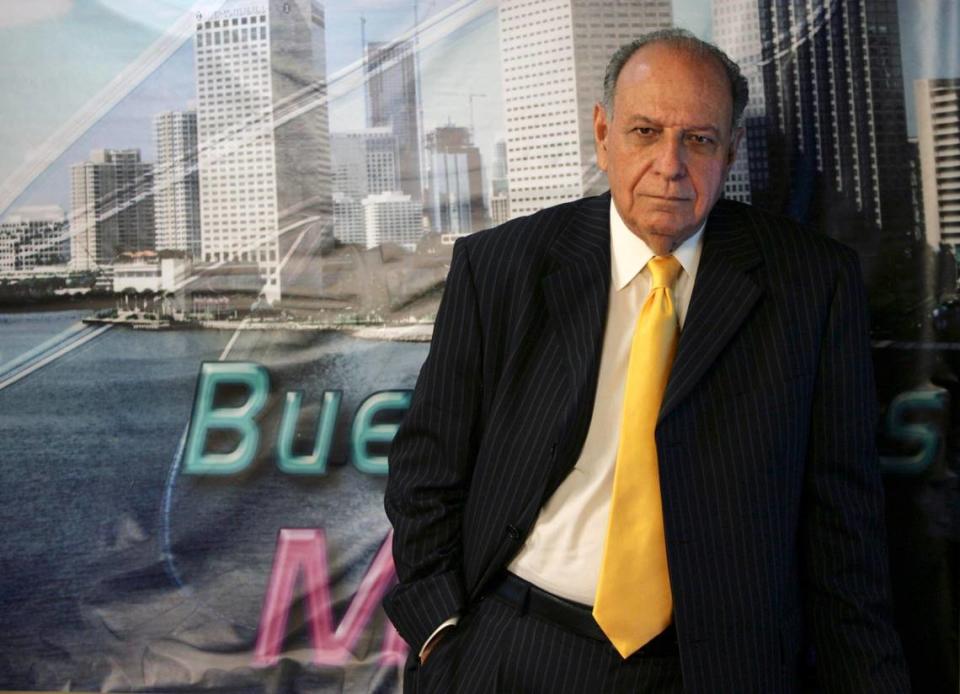

Miami radio pioneer and mentor to many, Tomás García Fusté dead at 93

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Tomás García Fusté, one of the most important and beloved Spanish-language radio personalities in South Florida, died in Miami early Monday. He was 93 years old.

Fusté was the voice of WQBA La Cubanísima in the 1980s and 1990s. For many years, La Cubanísima was the most popular radio station in Miami, with Fusté as general manager, and personalities such as Agustín Tamargo, Fernando Penabaz, Jaime de Aldeaseca, Néstor Cabell, Aleida Leal and Martha Flores, known as “The Queen of the Night.”

Colleagues remembered him as a man with extraordinary charisma, a peacemaker, adored by audiences, a great leader and someone who was always willing to help his community. Fusté also opened doors for many young people who later reached prominent positions in media and politics. Those included former Miami Mayor Tomás Regalado.

“The first voice that identified the Cuban exile community was Fusté,” says Regalado, who at the age of 16 began working with Fusté at La Fabulosa, the first station in Miami to broadcast programming in Spanish 24 hours a day.

“Many people don’t know why they call me ‘Tomasito’,” says Regalado. Regalado still hears people use the nickname that Fusté gave him as a reporter so as to distinguish between the two on air.

A mentor for young Miami radio stars

Fusté gave opportunities to young people who were starting out in Miami, not just radio personalities who were already established back in Cuba, Regalado said.

Cuco Arias, who became the producer of “Sábado Gigante,” and Pedro De Pool, who developed a career as an actor, were Regalado’s colleagues at La Fabulosa.

Born in Cuba in 1930, Fusté was the television and radio image of major brands such as Trinidad y Hermanos cigars until he went into exile in 1960. Some of those posters and photos adorned the walls of the radio presenter’s office. Many of his colleagues called him “Negro Fusté” because he used that affectionate term with those close to him.

“He said with great pride that he was in charge of placing advertising on the buses at the Guanabacoa public bus terminal,” recalls journalist Amado Gil, who is also from that Havana neighborhood and was one of the young people who, upon his arrival from Cuba in 1988, Fusté gave a shot to at La Cubanísima.

When Gil finished his work writing the programs, Fusté used to ask him, “My friend, can you go cover this news on the street?” That’s how Gil became a reporter.

“He was a man with a lot of charisma, very cordial, who was very well-liked,” Gil said, recalling that Fusté was the kind of journalist who could call the governor of Florida — at that time, Lawton Chiles — and the governor himself would answer the phone.

He also used his platform to help his community. When a listener in need of a job called in, he told the person to call Luis Sabines — then president of CAMACOL (The Latin Chamber of Commerce of the United States), said Gil. Gil also witnessed the annual giveaways that La Cubanísima would have for residents of Miami.

“He managed stations when the radio was the thing that moved this city,” said Gil, who today works at Radio Martí.

Fusté cultivated social radio

Fusté preferred “social radio,” says journalist José Alfonso Almora, who worked at La Cubanísima as a reporter from 1987 to 1991 and hosted a morning show with Fusté.

“He had charisma for raising money for charities,” Almora says. “And he knew how to assimilate the new generations of exiles without fear.”

Fusté also gave a voice to the opponents within Cuba when there was a lot of distrust of people who were risking their lives under the Castro regime.

“Those phone calls that we see today, he was the first one to make them. He was attacked, he was criticized, but he was always a conciliatory man,” said Almora, pointing out that Fusté gave a job at the station to Ricardo Bofill, one of the founders of the Cuban Committee for Human Rights.

Businesswoman Remedio Díaz-Oliver also highlighted Fusté’s support for the American Cancer Society, which she chaired, and the help that Fusté could obtain for others by collaborating with Hispanic organizations.

“He is one of the founders of [today’s] Miami, someone that people respected and loved,” said Díaz-Oliver, indicating that the respect came from all corners of society.

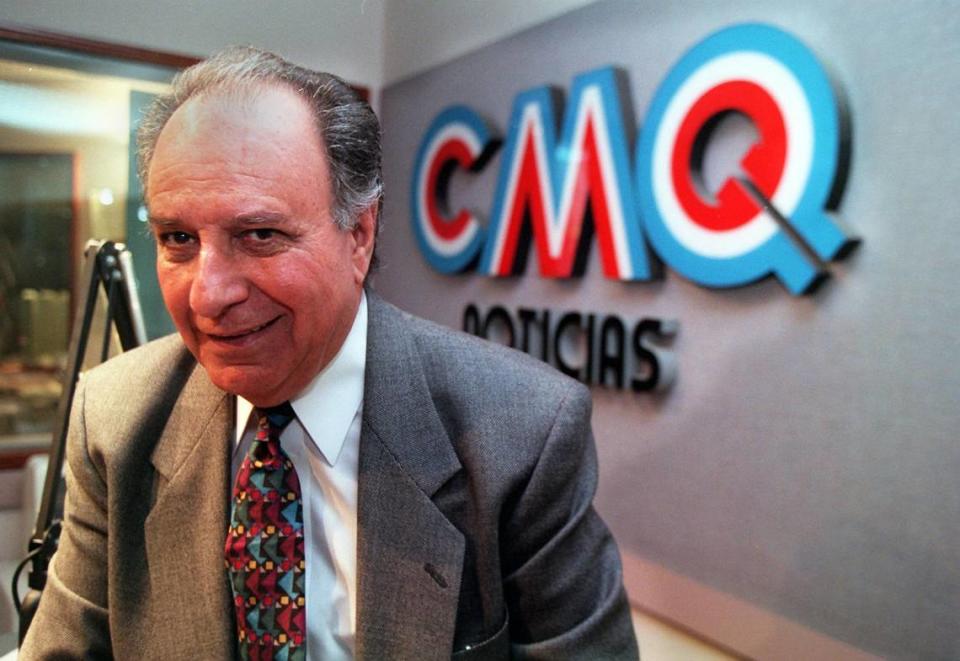

After La Cubanísima, Fusté continued his work in radio at Raúl Alarcón Sr.’s WCMQ 1210 AM, where he worked again with Regalado.

“Fusté was distinguished by two things. When there was a tragedy in another nation, in another region, he immediately organized marathons,” says Regalado, recalling the 24-hour fundraisers and the large containers that they put in La Fabulosa so that people could donate to help Nicaraguans affected by the 1972 earthquake that destroyed Managua.

“He also became interested in local politics and encouraged many, including me, to get involved,” says Regalado, who was one of the main guests on the program that Fusté hosted on Telemiami later in his career.

Fusté also presented the program “Tardes con Fusté” on América TeVé in 2017 with his third wife, journalist and writer Yurina Fernández Noa.

A street in Miami, a stretch of NW Seventh Street, was named Tomás García Fusté Way.

“Let us pause and thank God for living in a country of total freedom,” Fusté would say every day at noon on La Cubanísima, said Lourdes Rayón, one of Fusté’s daughters.

In addition to Fernández Noa and Rayón, he is survived by children Ana Dirube and Leo García, 10 grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

He will be cremated, and a Mass will be held later on, his relatives said.