Michael Parsons, brilliant civil engineer who revolutionised suspension bridge design – obituary

Michael Parsons, who has died aged 92, played a key role in designing and building four of the world’s greatest long-span suspension bridges – the Severn Bridge, the Forth Road Bridge, the first suspension bridge across the Bosphorus and the Humber Bridge.

He first became interested in bridge construction as an engineering undergraduate at the University of Bristol, partly inspired by Brunel’s Clifton Suspension Bridge across the Avon Gorge. After graduating with a First he joined the consulting engineers Freeman, Fox & Partners in 1949.

At that time suspension bridge engineers were seeking a way forward after the dramatic failure in 1940 of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge in Washington state, at the time the third longest suspension bridge in the world, due to a phenomenon called flutter. “When we started building the Forth and Severn Bridges,” Parsons recalled later, “we realised we would have to solve that problem.”

In fact the reasons for the failure of the Tacoma Narrows bridge were well known to Parsons, who had given a talk on the physics involved as an undergraduate and had concluded that, where suspension bridges are concerned, “the benefits of caution are considerable and the consequences of lack of caution can be disastrous.”

At Freeman, Fox his boss Gilbert (later Sir Gilbert) Roberts referred to Parsons as his “X-chaser” – the person who does the calculations (and finds the value of the algebraic “x”) – and as one of his early assignments he was put in charge of the crucial engineering analysis and structural calculations for the Forth Road Bridge.

The bridge, opened in 1964, was based on older American technology seen on San Francisco’s Golden Gate bridge and New York’s Brooklyn Bridge, with steel towers, steel decking, heavy supporting trusses and spun cables. Parsons’s calculations, however, enabled simplified fabrication and construction and a greatly reduced overall weight, saving on the cost of steel.

The original plan for the Severn Bridge was along the lines of the Forth Bridge with a truss deck structure, but Roberts wanted the truss to be shallower than on the earlier bridge, with the deck integral with the truss. But things did not go according to plan: during wind tunnel testing at the National Physical Laboratory, the model collapsed.

Knowing that the project, being run by Freeman Fox with Mott, Hay & Anderson, was shortly due to go to tender, Parsons told Roberts that he had a possible alternative to the truss which involved building the roadway from metal boxes or box-girders: “I had a drawing of a possible plated box. I knew from calculations it would be safe and have torsional stability.” The Germans had been building box girder bridges for some time, but this would be the first time a box deck structure was used on a suspension bridge.

Instead of having a stiffening truss under the roadway, the Severn Bridge was constructed of 88 separate plated boxes, made at the Fairfield shipyard in Chepstow. These were erected separately and welded together to form the box deck structure, which was streamlined in cross section, greatly reducing the force of the wind on the structure. It was also torsionally stiff, and would therefore resist any tendency to flutter.

Moreover where cables on other suspension bridges hung vertically, on the Severn Bridge they hung diagonally, helping to prevent the relative longitudinal movement between the cables and the deck which occurs when the deck twists – as happened at Tacoma Narrows. The plated deck structure meant that the bridge was the lightest suspension bridge in the world for its span and loading, so the towers did not have to be as strong, giving the structure a spare, elegant beauty.

Parsons served as resident engineer during construction in the 1960s as the first boxes were lifted into the middle of the bridge, having been floated across the water. It took 18 months to get all 88 in place partly due to the huge tidal rise and fall of the Severn.

The bridge was opened in 1966 by the Queen, carried the M4 motorway for more than 30 years and was granted Grade I listed status in 1999. Its revolutionary streamlined bridge deck was adopted not only for subsequent bridges designed by Freeman, Fox, including the Humber and Bosphorus bridges, but also by increasing numbers of designers throughout the world.

The design team was awarded the first MacRobert Award for engineering innovation in 1969.

“I feel I did a good job,” Parsons said. “But engineers don’t go around saying what marvellous guys they are. They just solve problems. I knew something would work and I had the confidence to tell my boss it would and it did.”

The second of four children, Michael Francis Parsons was born in Bristol on October 16 1928. His father was a plumber while his mother ran a shop selling and repairing umbrellas.

From Cotham Grammar School he went up to Bristol University to read Engineering. His career at Freeman, Fox was interrupted in the early 1950s by two years’ National Service in the Royal Engineers, spent mainly in West Germany. He remained with the firm until his retirement, becoming a partner in 1974. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Engineers.

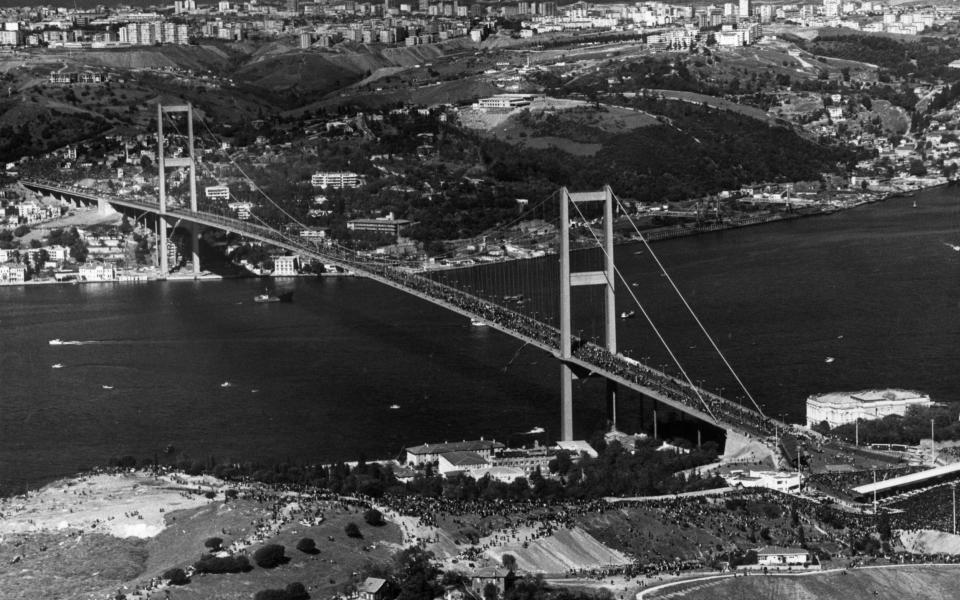

Parsons worked on the design of the first Bosphorus Bridge which, on its completion in 1973, had the longest suspension bridge span outside the US, and was project engineer, superstructure, for the Humber Bridge which, when it opened in 1981, was the longest suspension bridge in the world.

His later work included evaluation of designs for the Channel Crossing and projects in India and Hong Kong. He ended his career doing outline drawings for a bridge across the Strait of Messina between Italy and Sicily which, if built, would become the world’s longest span bridge.

Parsons recalled that, on a flight to India, he had looked out of the plane window and seen the Bosphorus bridge that he had designed, “glintering in the sun”: “Leaving something that you can see and admire from 35,000 feet can’t be all that bad ... it’s the shape of the curve and the apparent efficiency of the whole thing: well it’s a work of art I suppose.”

He was less impressed with the Second Severn Crossing, a cable stayed bridge opened in 1996 to carry the M4: “I was disappointed because I couldn’t see anything because of the wind barriers. When you go over the old Severn Bridge you feel as though you’re king of the world. There is no comparison.”

After his retirement Parsons settled in Sidmouth where he took up golf.

He is survived by his wife Joan, née Wickett, whom he married in 1951, and by two of their three sons.

Michael Parsons, born October 16 1928, died April 20 2021