Who is Michael Rhynes? The story behind an exonerated Attica prisoner who remade his life.

"How does the innocent seek redemption?"

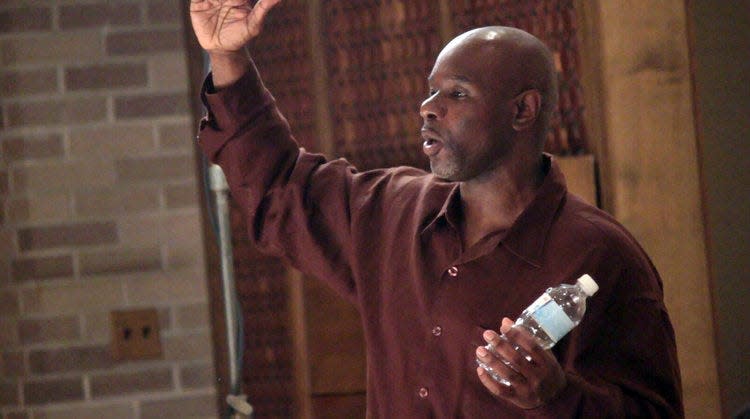

It is April 2012. A small chapel inside Auburn Correctional Facility has been converted into a theater, where a few dozen outsiders have passed through the metal detectors and behind the clanging gates to watch the Phoenix Players Theatre Group.

The play is "Maximum Will," an original piece combining Shakespeare with elements of the incarcerated actors' own lives. Michael Rhynes, one of the group's co-founders, is at center stage.

"Sitting in a six-by-eight cage in the dark with all the lights on," he continues. "Searching in and behind the toilet. Leafing through three holy books, to no avail."

In between lines, he dances a few steps with a woman, an outside volunteer. This was an important element of the production for him: dancing represents freedom and fluidity, he believes, within the rigidity of prison.

She lets go of his hand and he continues with a line that Shakespeare wrote for King Macbeth: "Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow, creeps in this petty pace from day to day."

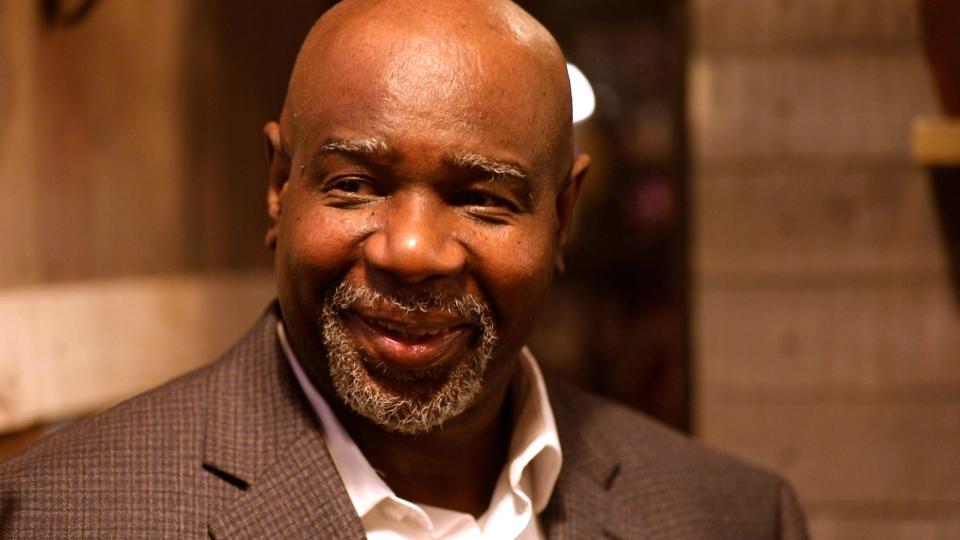

Rhynes, 62, has been thinking about the redemption of the innocent for his entire adult life. He was arrested in October 1984 in connection with a double-murder at a Rochester bar. Two years later he was convicted and sentenced to 52 years to life despite the absence of any physical evidence or eyewitness account connecting him to the scene of the crime.

This week he walked out of prison after 37 years. A state Supreme Court judge ruled his conviction had been based on lies. Two men who initially testified against him recanted under oath earlier this year, saying they'd done so in exchange for help with their own legal problems.

But legal redemption is different from spiritual redemption; one does not purchase the other.

At the same time Rhynes was filing appeal after appeal — a creeping process, a petty pace — he was also transforming himself and others inside the maximum-security walls of Attica and Auburn correctional facilities.

'Mike is a light. He's just pure wisdom.'

Much of that work was done through programs he founded or led, the Phoenix Players being first among them. He also started a poetry group and published his own book of poetry. He helped arrange a visit from opera singers from the Glimmerglass Festival and sang in the choir alongside them.

He worked on HIV/AIDS awareness and helped create domestic violence prevention classes for veteran inmates so they could deal with their anger before they returned home to their loved ones. He led the Quaker meeting in Attica for a time and also worshiped with Buddhists.

He even performed a piece for TedX Attica with the head of the state Department of Corrections and Community Supervision in attendance.

"Anyone who ever came across Mike would tell you: Mike is a light," said David Bendezu, who was incarcerated with Rhynes in Auburn. "That’s just who Mike is. ... You’d never know the struggles and pain he’s been through. He’s just pure wisdom."

Difficult early life in north Rochester

Rhynes was born in 1961 and grew up on the city's north side, largely in the Joseph Avenue neighborhood. It was a difficult time and place for a child and his life was marked early by violence.

When he was six years old, Rhynes' father was shot in the back and afterward remained in a rehab facility. Rhynes himself was shot three days after Christmas 1976, during a brawl at a downtown theater.

He was 15 years old then and had already dropped out of school, only having completed the eighth grade.

"He was a street guy; he did what the streets did," said his sister, Petronia Rhynes. "He had to survive, so that’s what he did. Most all of the young men did that."

In the absence of his father, an education or any meaningful economic opportunity, Rhynes was headed down a dangerous path.

At the time of his wrongful arrest he had charges pending related to an assault and attempted robbery the previous year. And before his 1986 trial began, he got into a fight with a jail deputy in the courtroom.

"He was innocent of this crime, but he wasn't an innocent," said Bruce Levitt, a Cornell University theater professor who facilitates the Phoenix Players Theatre Group.

That was Michael Rhynes in 1986: traumatized, directionless and angry, with 52 years or more still to serve.

'To bring forth our humanity'

The first step toward redemption, he said, was poetry.

He began a few years into his sentence, part of an educational trajectory toward first a general equivalency diploma and then an associate's degree from Cornell University.

In 2009 Rhynes published a book, "Guerrillas in the Mist, and Other Poems." The poems in it connect national and world politics with the suffering in American neighborhoods like the one where he grew up as well as his experience in prison.

"Poets were created to combat interior as well as exterior tyranny," he wrote to one reviewer.

Before long, poetry led to theater. Part of the connection was Rhynes' love for Shakespeare, who he called "a breathing apparatus that helps one go deeper into the undiscovered country of themselves."

In 2008 he and another inmate were taking acting classes and had the idea of expanding to a full-fledged theater company. The goal, as Rhynes wrote in an early manifesto, was "to reconnect us to society, our communities, and our families, by learning through drama how to love, what it feels like to be compassionate, to forgive and be forgiven, to reach into the depths of our beings and bring forth our humanity."

The group put on its first production in 2011, and has four more since then. Their work was featured in a 2019 documentary film, "Human Again."

One of the early inmate-actors was Demetrius Molina, who knew Rhynes from working together in a transitional program for inmates on their way out.

Molina was only a few years into his sentence and wasn't initially sure about joining a theater group — especially one that would require deep introspection, as Rhynes envisioned.

"I was young, I had a lot of time to do, I was still impressionable," said Molina, who left prison earlier this year. "I didn’t have a lot of positive outlets to keep me grounded and centered, because there’s so much violence and negativity in there that you go through on a daily basis. ...

"He honestly is the person who saved my life. And I told him that numerous times over the years. ... That was the time I could open up and take the mask of prison off and just really be myself. I don't know how I would have gotten through that time without Phoenix Players."

Levitt, the Cornell facilitator, said Rhynes has "a kind of Buddha-like wisdom" that helped him on the stage and also in selecting the inmates who would be invited to participate.

"They wanted people who were ready to do some really deep, personal explorations," Levitt said. "Michael has a way of bearing down on you and looking you in the eye and very directly finding out what you’re about. ... He had a sense about who was ready. And sometimes the person didn’t even know they were ready, but Michael knew they were ready."

It was Rhynes who named the group the Phoenix Players. He wanted it to be a symbol of the men's transformation and renewal.

"We were looking for a place where we could heal, not just an acting program," he told one researcher. "Just being actors isn’t good enough for us. We had to learn who we are."

'An incredible force in Attica'

As the years passed by, Rhynes became an elder statesman of sorts in prison, both because of his age and the amount of time he already had served.

David Bendezu, who served with him in Auburn, said that most inmates in that position have lost all hope.

"There are people doing a lot of time that are bitter, and rightfully so sometimes," he said. "Mike never let it eat him up. ... You’d never know he was serving so much time from the way he carried himself. He’d listen to your pain before he’d share his own pain."

Deborah Kilbourne first met him 30 years ago after a mutual acquaintance showed her a poem Rhynes had written about battered women. It was she who helped organize the legal strategy that eventually freed him.

"It’s hard to know you didn’t do something and yet you’re in prison all those years," she said. "But he always put his energy into his programs and productive things. ... He's just been an incredible force in Attica."

On more than one occasion, Rhynes said he no longer feared dying in prison because he knew the art programs he created were helping the men around him.

At the end of the "Maximum Will" performance in 2012, he reflected on how his time in prison had changed him.

"Even though I hate this place, I don’t like being here – I grew up in prison," he said. "I am doing things I never thought I could do, like going to college, acting, writing. Things I’ve always had the potential to do but never could. ...

"It’s been a hell of an odyssey and I’ve grown immensely. (But) I wouldn’t do it again."

— Justin Murphy is a veteran reporter at the Democrat and Chronicle and author of "Your Children Are Very Greatly in Danger: School Segregation in Rochester, New York." Follow him on Twitter at twitter.com/CitizenMurphy or contact him at jmurphy7@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Rochester Democrat and Chronicle: Prison didn't break him. Theater, study, fellowship saved Michael Rhynes.