Michigan bill banning codes in public documents comes after symbols found in email

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A Michigan Senate Republican wants to ban the use of codes and symbols in public documents, a move aimed at preventing secrecy devised to circumvent public records laws.

State Sen. Ed McBroom, R-Vulcan, a longtime open government advocate, argues the bill is needed due to a specific issue: In 2021, a lobbyist and adviser working with the administration of Gov. Gretchen Whitmer on a water crisis sent an email to a key Whitmer adviser that included at least one unreadable passage.

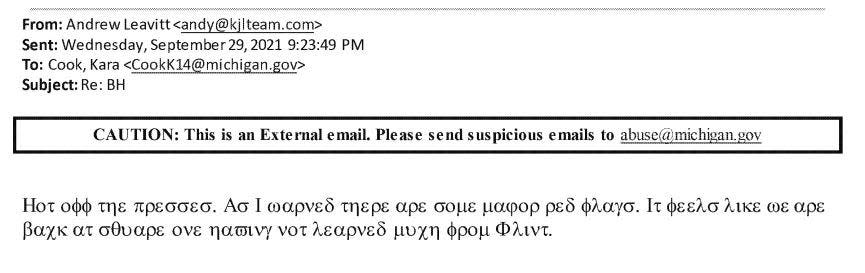

In the email, obtained by the Free Press, those sentences are in the “symbols'' font instead of English, making it indiscernible until the message is swapped to a more traditional font.

Only then can a reader see what was sent: “Hot off the presses. As I warned there are some major red flags. It seems like we are back at square one having not learned from Flint.”

The message, from lobbyist and consultant Andy Leavitt, came in an email to Kara Cook, then a senior Whitmer adviser on energy and environment. It came at a time of increased publicly scrutiny of the state's response to a water crisis in Benton Harbor, a southwest Michigan community with many lead service lines.

“My legislation would help ensure FOIA works to help hold government officials accountable by clarifying the intent of the law and the penalties for failing to do so,” McBroom said in a statement.

“Whether this incident was the result of a coding glitch or an intentional effort to hide their statements from the public, we should all be able to agree that we need better protections in place to preserve communications in a way that doesn’t avoid honest disclosure."

To be clear, most of the email is not in symbols. Leavitt's remaining comments provide sharp critiques of a draft document intended for Benton Harbor residents, but are not as broadly critical of the state’s response to the water crisis as the passage in symbols.

On Tuesday, Leavitt said he was "absolutely not" trying to communicate in code. He said he believes he copied bullet points from a document on his phone into an email. The bullets were apparently in the symbols font.

He then typed a few more sentences above the bullets. Those sentences appeared in English on a mobile device, but in the symbols font when read on a desktop computer. The Free Press was able to replicate this scenario.

It was a mistake, involving an error with copying and pasting information, that he says has spiraled out of control.

"I would say that the people who know me know I've never shied away from telling the truth and being honest with people. In life, usually the simplest answer is probably true. And this case is one of those," Leavitt said.

"A cut and paste and weird formatting issue has created and birthed a wide conspiracy — largely around the idea that you could hurt the governor with it — and it couldn't be further from the truth. I did nothing more than cut and paste a document and send an email."

More: Former Rep. Mike Rogers jumps into Michigan's US Senate race

More: Ex-Macomb public works commissioner Anthony Marrocco released from federal prison

Earlier this summer, conservative media outlets reported on the email with symbols. The story made its way through several high-profile conservative outlets, including the New York Post, flaming what Leavitt described as the conspiracy surrounding the email.

Representatives for Whitmer declined to comment.

Lawyers and Benton Harbor residents suing the state over the southwest Michigan city's lead water crisis first discovered the email, highlighting it in their federal lawsuit. Mark Chalos, a Tennessee-based lawyer representing the Benton Harbor residents, said it does not matter whether Leavitt intentionally meant to send an encoded message.

“However those very damning statements in that email turned into Greek symbols, whether it was done when the guy typed it or it was done when they produced it to the public and us, the fact remains that those very damning statements were not readable to the public or the Benton Harbor people. It’s not terribly important to us how the sentences got hidden," Chalos told the Free Press.

His team referenced the symbols in a federal court filing. The state had the opportunity to explain in a response filing how the message made it into a public email. It did not.

The Free Press submitted a Freedom of Information Act request to two Michigan departments; copies already provided to the Free Press indicated the leaders of both agencies received the email.

The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services denied the request, saying the system the state uses to quickly search through emails could not do so using symbols. A comparable search by hand would cost “hundreds of thousands of dollars” to complete.

The Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy also originally denied the request, but later provided the email after the Free Press asked a department spokesperson why the agency could not locate the communication.

“The whole reason why we have FOIA and other government transparency provisions is to make sure that our government is being honest with us. I mean, because it’s our government. We’re paying for it; we’re electing these people,” McBroom previously told the Free Press.

“If they can be allowed to hide communications and speak in codes to each other, that’s just running totally counter to these transparency laws, we can just as well not have them at all.”

McBroom's bill creates a new section of the Freedom of Information Act, outlining proposed prohibited behavior. Under the proposed measure, a state agency violates records laws if it creates or retains a public document that includes "code words or phrases, symbols, foreign language or non-English letters or characters, or any other content not readily associated with the true subject of the record..."

If an agency has a record that does use any language referenced in this bill, and that record is subject to disclosure laws, it must create a description in English that shows meaning of the phrases used in the original document.

“I began work on this bill more than four months ago, long before various groups and media started talking about this particular email," McBroom said in a news release.

"My intention has always been to fix an apparent problem so no one in the future is inspired to try to hide information this way while also bringing attention and accountability to this situation if, in fact, it was intentionally done.”

While McBroom, state Sen. Jeremy Moss, D-Southfield, and many other lawmakers consistently advocate for beefing up Michigan's public transparency laws, the bills frequently fail to make it out of the Legislature.

Whitmer and Democrats have said bills to include the governor and lawmakers under the Freedom of Information Act are a priority with the party’s legislative majority. But legislators have yet to send any bills of this nature to the governor for her signature.

Michigan and its state government are considered one of the least transparent in the nation. It’s one of the only states that has completely exempted the governor’s office from public records disclosure laws.

Whitmer and leaders of the state health and environmental departments have repeatedly defended their actions in Benton Harbor. But Free Press stories and many additional media reports show regulators failed to bring down lead levels in Benton Harbor for more than a year, despite test results showing their attempts to curb the problems were not doing enough.

After substantial community pushback in fall 2021, Whitmer and lawmakers worked to secure additional funding for new water service lines in Benton Harbor. The new money for Benton Harbor helped the city replace pipes on a much faster timeline than originally planned.

As of November 2022, more than 99% of old service pipes were replaced. In June, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency released the city from actions required under an administrative order, noting that recent water tests show lead levels deemed “acceptable” under federal guidelines.

The state asked a federal court to toss Chalos’ lawsuit. The case remains open, as do related lawsuits at the state level.

Reach Dave Boucher at dboucher@freepress.com and on X (formerly known as Twitter) at @Dave_Boucher1.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Michigan bill would ban codes in records after symbols found in email