Michigan hospitals receive grants to prepare for the next pandemic

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Michigan hospitals get federal grants

Ebola, Lassa, yellow fever, Marburg.

Though none of these highly contagious and often-deadly viral hemorrhagic fevers are endemic to the U.S., millions of dollars have been spent since 2014 to prepare for the possibility that travelers could bring them here and spark an outbreak, or that a new and dangerous virus could emerge, threatening public health.

Corewell Health Butterworth Hospital in Grand Rapids got a $3 million grant this fall from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to expand its ability to handle cases of these and other extremely infectious diseases. It is now one of 13 regional centers in the U.S. with this designation.

Prepping for 'a laundry list of highly fatal conditions'

And because of its affiliation with Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, it is one of only three nationally with the ability to treat children who become infected, said Julie Bulson, director of business assurance for Corewell Health.

“There is certainly a laundry list of highly fatal, potentially contagious conditions that are not endemic to the United States that could be brought in,” said Dr. Russell Lampen, medical director of infection prevention for Corewell Health West.

In addition to viruses like Ebola, “these special pathogen units have been used for things like multidrug-resistant tuberculosis — things that are not necessarily exotic but are difficult to manage and things that we certainly don't want out in the community and that we want to control,” Lampen said.

Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit got a little over $750,000 in recent years to upgrade its sixth-floor special pathogens unit. Federal grants also were awarded to three other Michigan hospitals that are designated as Tier 1 or Tier 2 medical centers — Corewell Health Wayne Hospital, Trinity Health’s Ann Arbor and Pontiac Hospitals.

U.S. health leaders have spent years planning how to handle potential cases. They’ve trained special teams of medical workers and developed a network of regional health care centers equipped to recognize, manage and isolate future outbreaks — all in preparation for the possibility that Ebola or another new, dangerous virus could emerge.

More:Michigan's COVID-19 death toll passes 40,000 — and where they're dying has shifted

More:32% of Michigan toddlers at risk for preventable diseases as vaccination rates fall

Why these units are special — and important

In Michigan, those five hospitals have Tier 1 or Tier 2 designations, which means they are able to care for patients with these viruses — with specially designed personal protective gear to keep medical workers safe, negative pressure rooms to contain viruses and connected anterooms for donning and doffing PPE.

About a dozen more Michigan hospitals have Tier 3 designations, which means they would accept and stabilize patients with these very infectious diseases, and then transfer them to a Tier 1 or Tier 2 center.

“The U.S. Public Health Service is trying to create this network of different levels of care,” said Patricia Starr, infection prevention specialist at Henry Ford Health.

“Even though ours is a small unit, we still fill an important niche for that type of care because we can give them containment, safe health care, staff who are protected and trained properly. We can do the diagnostic work. And then we will always be communicating with the state health department and with" the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

How the U.S. is responding to the latest Ebola outbreak

An Ebola outbreak that began in September in Uganda has infected 142 people as of Dec. 8, killing 55, according to the World Health Organization. It prompted the U.S. to begin screening and monitoring all travelers from Uganda for 21 days after their arrival.

It’s one of several surveillance systems now in place to detect the spread of new and highly infectious pathogens with an aim of stopping the next viral scourge before it takes hold.

In Michigan alone, 105 travelers have been monitored for Ebola symptoms as of Dec. 6, said Joe Coyle, director of the Michigan Bureau of Infectious Disease Prevention; no infections have been identified.

“Those travelers are persons that either are leaving from or have traveled through Uganda who are arriving in the United States,” Coyle said. “They're being triaged through five airports in the U.S. and the federal government is doing a fairly robust job of doing screening of travelers … and then referring that information to the states that might be the final destination for those travelers."

Anticipating whether the next major viral threat will be Ebola or a similar hemorrhagic fever or an entirely different virus is difficult, Coyle said.

“Every pathogen is different,” he said. “You can see even today, our health care systems are being stressed right now by RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) and influenza.

“So even sort of regular, routine pathogens are always posing a threat. Whether we have co-circulating pathogens with patients that are competing for hospital beds, whether you have a respiratory virus or something else, there's always, always a concern. Every novel pathogen is going to be a little bit different and the needs locally in our ability to control it could be very different.”

COVID exposed problems in U.S. preparedness

When the first wave of the novel coronavirus crashed over the U.S. in early 2020, health leaders tried to assure the public that the virus could be stopped and that the nation and state were prepared.

But it soon became clear that there was no containing the coronavirus. Nearly three years later, it continues to circulate widely and killed an average of 29 people each day in the last month in Michigan alone, according to a Free Press analysis of state data.

The COVID-19 pandemic also revealed gaping holes in the U.S. preparedness plan.

The national supply chain for personal protective equipment for medical workers — such as masks, respirators, surgical gloves and gowns — were sourced almost entirely from China, the epicenter of the initial outbreak. That meant American hospitals couldn’t get the supplies they needed to keep health care workers safe.

More:Michigan nurses say they don't have masks, gear to keep them safe from coronavirus at work

More:Simple lung cancer screening test is easy, painless — and could save your life

The Strategic National Stockpile’s supply of those products wasn’t robust and included PPE that was so old, the elastic on masks disintegrated upon use.

“That hamstrung all of us a bit,” said Jay Fiedler, director of the Michigan Division of Emergency Preparedness and Response. “We've learned a lot about stockpiles and even the Strategic National Stockpile at the federal level has adapted to be more responsive.

Since then, sourcing for PPE supplies has diversified and now includes products from U.S. and international manufacturers.

As Fiedler looks ahead at preparedness for the next emerging disease, he’s said he’s most concerned about how hospitals and other health care organizations will find enough trained workers.

“The Achilles heel of this will be staffing,” he said, “at the long-term care level … at the EMS (emergency medical service) level … everyone is understaffed — from pre-hospital all the way through discharge and post-hospital care.

“It has been tough and that's going to be hard to address in the short-term but it's going to be definitely something we look at in our response to anything moving forward.

More:With EMS staffing crisis brewing for decades, COVID pushes shortage into danger zone

More:Exhausted and abused, Michigan nurses are searching for new jobs, or reasons to stay

“COVID overwhelmed everyone for sure. You can't anticipate the next COVID … but I think we are ready to respond to a lot of the things that could come down the pipe.”

The country now has a solid infrastructure to deliver vaccines and treatments to the public, he said, and a strong network of hospitals with special pathogen units, Fiedler said.

The Michigan Bureau of Laboratories is part of the national Laboratory Response Network, he said, which means the state can do its own testing for Ebola.

“We don't have to rely on somebody else to do that for us,” Fiedler said.

The value of sewage surveillance

Since COVID-19 struck, the nation also has gotten far better at detecting the spread of viruses, Fiedler said.

“Surveillance will always be the backbone of these processes,” he said.

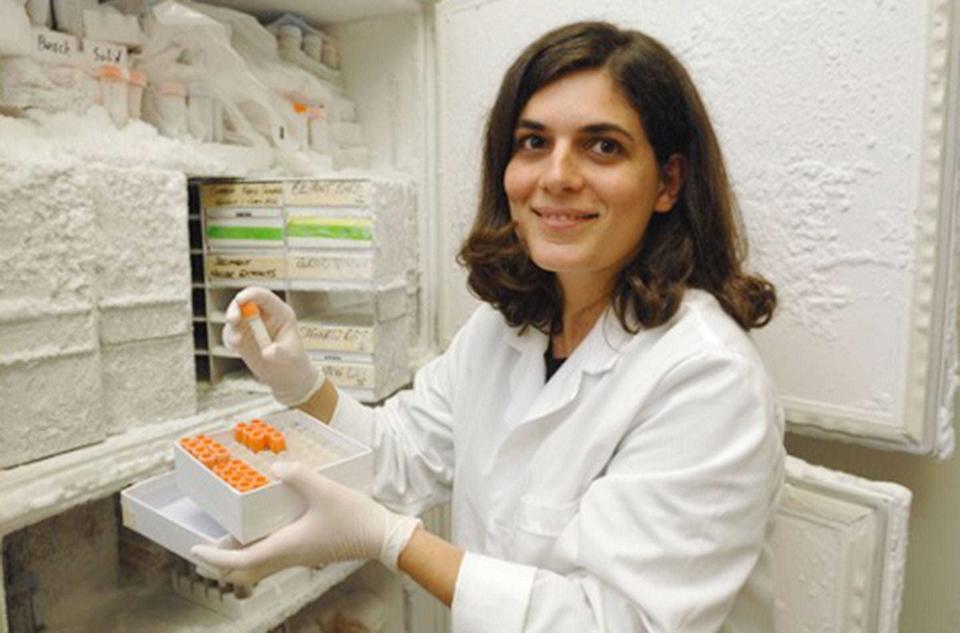

One of the ways public health leaders are looking for emerging diseases is through wastewater testing — a process pioneered by Irene Xagoraraki, a professor of environmental engineering at Michigan State University. She tested sewage samples for multiple viruses, including hepatitis A, and developed a wastewater-based prediction system for viral outbreaks in urban areas.

Her research team was awarded a National Science Foundation grant in 2017 and tested wastewater from the city of Detroit.

“I had been studying viruses in wastewater and natural waters for the last 17 years, but I was always looking at it in terms of removal … from drinking water and removal from wastewater," Xagoraraki said. "At some point, I realized that maybe we can use the methods as a surveillance tool to monitor community health. At that time, I was doing research work in Uganda, France and Michigan.

"In my lab, we observed different diversity of human viruses in the different locations. Then, it came to mind that wastewater surveillance could be an effective tool for predicting viral-related disease and used as a way to predict surges of certain viruses over time.

“It was early, exploratory research and we didn't know if it was going to work. But it did work, and we published the results and methodology, which then became widely used during the pandemic.”

'Oh, we could use that for COVID'

Xagoraraki’s system was adapted to allow scientists to test wastewater samples for the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes COVID-19.

“I was presenting the Detroit results at a conference and Dr. John Norton, who is the head of research at the Great Lakes Water Authority, saw my talk and he's like, ‘Oh, we could use that for COVID,'" she said.

"I worked with the Great Lakes Water Authority and we published data on SARS-CoV-2. The state of Michigan saw the work and funded my lab to expand the research. The city of Detroit was the very first wastewater facility in the country that adopted the methodology of wastewater-based-epidemiology prior to the current pandemic.

“I published data, and the state of Michigan saw that data and they funded me to expand the research. Now, everybody's doing it. But the beginnings of it were not simple.”

Norton said Xagoraraki’s work is revolutionary, and can now be used to detect all sorts of viral threats.

“This is a really important opportunity,” he said. “Everybody pees and everybody poops, and when they do so, we have their data. … It can tell way in advance of medical diagnosis that there is an emergent outbreak of some sort of disease, can provide data regarding the effectiveness of a certain treatment or program to confront a disease, and provide other information regarding new and emerging diseases.”

Wastewater-based surveillance has been used to detect polio in New York state and can be expanded to other emerging viruses. The CDC and Michigan Department of Health and Human Services announced they will soon begin testing Oakland County wastewater samples for poliovirus as well.

More:Michigan to begin testing wastewater for polio

More:Michigan health leaders on 'high alert' for polio as vaccination rates continue to fall

The importance of an international network

Dr. Russell Faust, Oakland County's medical director, praised the foresight of the leaders at the CDC to invest in wastewater surveillance.

“One of the things that CDC did intentionally was a set up a national network of laboratories, but not just laboratories, collaborative teams,” Faust said. “They set up these collaborative teams that include medical directors, health officers for public health, epidemiologists from public health and the statisticians and laboratory people and the at the wastewater treatment sanitarians, all the field technicians and everybody.

“It's a huge team of people required in each one of these sites to do the SARS-CoV-2 testing. They intentionally invested in that, knowing that at some point that would no longer be of value for COVID, but looking ahead to other potentially emerging pathogens.

“I think it was just a stroke of genius to do this. Because that's a national network right now. In fact, international. Other countries have done this, and moving forward as we have emerging pathogens, this will help save a lot of lives.”

As Lampen looks ahead to the potential for other viral outbreaks of highly infectious diseases, another source of comfort is knowing that the mRNA vaccine technology developed by Pfizer and Moderna, used for the first time during the COVID-19 pandemic, could be a blueprint to quickly make new vaccines to target other viruses.

"If we had a bird flu or a swine flu outbreak," he said, "mRNA technology could be used to help us develop rapidly a new vaccine for distribution. I know that there has been a lot of pushback against those mRNA vaccines, but I do think that if we had a disease that was spreading with a higher fatality rate than COVID — if it was more like SARS-CoV-1 — I think you would find people far more willing to accept those vaccines.

"As we ... have more and more comfort with mRNA vaccines, it will no longer be new technology. It will just be like any other vaccine that people receive."

The ripple effects from the COVID-19 pandemic stretch far and wide, he said.

"We now have this structure in place that we used when monkeypox came," Lampen said, "to distribute monkeypox treatment and vaccines. And I think monkeypox is an example of another emerging pathogen that popped up.

More:Michigan's first probable case of monkeypox virus is in Oakland County

"You can see how quickly, with a good public health background and backbone, that we were able to get on top of that outbreak. It's really quieted itself down to the point where it's no longer a concern."

When he talked to medical workers about the threat of monkeypox earlier this year, he was surprised to find that many of them didn't seem fazed. Working through the coronavirus pandemic seemed to make them less concerned about the infection risk.

"It was a bit of a shrug to shoulder," he said. "They were like, ‘What do we need to do? ... Whatever. I'm in. We're here.'

"There has been a little bit of a resetting where health care providers now understand that there is a potential for personal risk as we deal with new infections. And I think that mindset now exists and people are more ready to deal with new threats as they come."

Contact Kristen Shamus: kshamus@freepress.com.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Michigan hospitals get grants for pandemic preparation