Flint Water Crisis Victim Slams Court’s ‘BS’ Decision to Spike Charges

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Charges against former Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder and eight others in the Flint water contamination scandal have been dropped by the state’s Supreme Court.

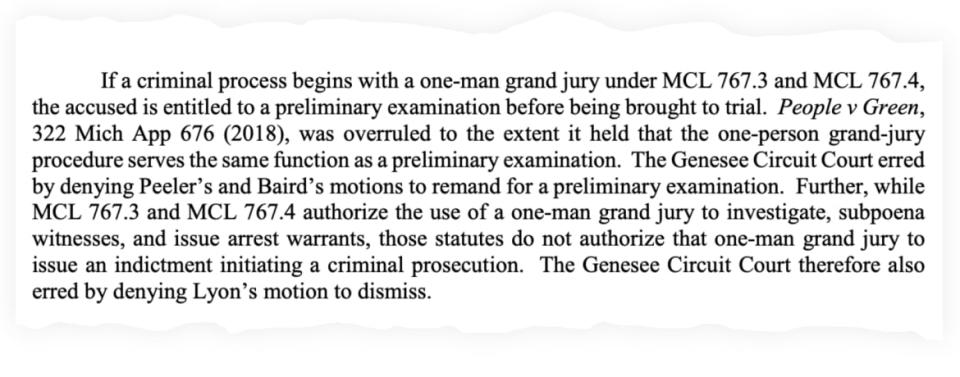

State laws merely “authorize a judge to investigate, subpoena witnesses, and issue arrest warrants,” but “do not authorize the judge to issue indictments,” the court’s 6-0 opinion reads.

Attorney General Dana Nessel took office in 2019, and assembled a new team to investigate Snyder and a slew of advisers and officials who were in charge when Flint’s water supply became contaminated with lead beginning five years earlier. An outbreak of Legionnaire’s Disease in 2014 and 2015 was attributed to issues with the city’s water, as well.

Their alleged crimes included, among others, misconduct in office, willful neglect of duty, and involuntary manslaughter. Genesee County Judge David Newblatt reviewed the evidence and issued indictments as a so-called “one-man grand jury,” Tuesday’s opinion argues.

Newblatt “considered the evidence behind closed doors, and then issued indictments against defendants,” the opinion states, noting that—unlike a grand jury made up of citizens, a “one-man grand jury,” that is, a judge, do not require a jury oath and thus “cannot initiate charges by issuing indictments.”

Nakiya Wakes, who moved to Flint in June 2014, told The Daily Beast on Tuesday that she was shocked and dismayed at the news. Beginning a year after arriving in the city, Wakes suffered at least two miscarriages. Her children, Jalen and Nashauna, both tested positive for lead in their blood after the family settled in Flint.

“It’s straight BS,” Wakes said in a phone call following the court’s decision. “Nobody is being held accountable for their actions. This, for all of us, it’s like we have no justice at all... There were deaths from Legionnaire’s Disease, all these kids were poisoned. We don’t know what’s going to happen to us 10, 15 years down the line, and nobody is being held accountable.”

Flint resident Nayyirah Shariff, a community organizer and founder of the Flint Rising advocacy group, told The Daily Beast that the court’s decision came as “just a blow out of nowhere.”

“It feels increasingly clear that it doesn’t really seem that the justice system is a viable option for people to receive justice,” Shariff said on Tuesday. “We’ve done all the ‘things,’ you know? We’ve sent buses to D.C. and our state capitol in Lansing, spoke with legislators, got policy changes, marched in the streets—did all that stuff, and it left me thinking that at the end of the day, the price of bearing our trauma to the public was that there was going to be some sort of accountability at the end of that tunnel. And... [here’s a] majority Black city, one of the largest health disasters in the history of the country, and there’s no consequences? Like, what the fuck?”

And whistleblower LeeAnne Walters, a mom of four in Flint who was largely responsible for exposing the water crisis to begin with, told The Daily Beast: “Maybe these people should actually think about all the harm they have caused to so many people and quit fighting responsibility. For once they should take responsibility for fact that they were paid to protect us and not only failed, but they did so with malice when they chose to ignore the cries of the people.”

In the Flint case, the accused were denied a preliminary examination of the evidence, according to the court.

“Given the magnitude of the harm suffered by Flint’s residents, it was paramount to adhere to proper procedure to guarantee to the general public that Michigan’s courts could be trusted to produce fair and impartial rulings for all defendants regardless of the severity of the charged crime,” the opinion says.

“The prosecution cannot cut corners—here, by not allowing defendants a preliminary examination as statutorily guaranteed—in order to prosecute defendants more efficiently. The criminal prosecutions provide historical context for this consequential moment in history, and future generations will look to the record as a critical and impartial answer in determining what happened in Flint.”

The crisis in Flint unfolded in April 2014, when the city switched its water supply from Detroit’s system to the Flint River. The nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) later called the cost-saving move a “story of environmental injustice and bad decision making.”

The plan was meant to be temporary, with water being pumped from the Flint River into homes only until a new pipeline from Lake Huron could be completed. In the meantime, Flint residents soon noticed that something was wrong with their water, which now looked, smelled, and tasted bad. As it turned out, old pipes were leaching lead into the water going to people’s homes, while government officials insisted everything was fine.

A year later, water samples collected by researchers would reveal an extremely serious problem, with lead far exceeding acceptable levels set by the federal government.

“When I saw those numbers I was shocked,” Virginia Tech professor and water-quality expert Marc Edwards said in 2015. “I have never in my 25-year career seen such outrageously high levels going into another home in the United States. This was literally hazardous-waste levels.”

In 2016, another study found that the level of lead in Flint children’s bloodstreams had nearly doubled since 2014, with numbers tripling in some parts of the city.

“Lead is a potent neurotoxin, and childhood lead poisoning has an impact on many developmental and biological processes, most notably intelligence, behavior, and overall life achievement,” wrote lead author and pediatrician Mona Hanna-Attisha. “With estimated societal costs in the billions, lead poisoning has a disproportionate impact on low-income and minority children. When one considers the irreversible, life-altering, costly, and disparate impact of lead exposure, primary prevention is necessary to eliminate exposure.”

In Flint, almost 9,000 kids were drinking lead-poisoned water for a year-and-a-half, according to the NRDC.

On Tuesday, Edwards told The Daily Beast in an email, “Those directly responsible were let off the hook long ago, so I’ve been skeptical about the entire case ever since. All of that time, money and raised expectations for nothing—it’s a worst case outcome. Maybe this epic story of government failure at all levels, was just destined to end in a fiasco like this…we will have to wait and see.”

Once a vibrant manufacturing town, Flint began a slow decline in the 1980s. With its population cleaved in half, more than 37 percent of people in Flint now live below the poverty line.

“Who the hell are we as country?” Shariff said. “It’s who we are, I guess... and the way we’re going is not a good look at all... There needs to be justice. We can’t have people in power continuing to protect themselves and not protecting people who are living with the consequences of elections.”

Got a tip? Send it to The Daily Beast here

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.