Michigan urban myths and legends: 7 stories to share around the campfire

Stoke the fire, prepare your s’more, and get comfortable — it’s about to get unnerving.

Michigan has many urban myths and legends, depending on how many people you talk to and how many books you read. But a few of them stand out above the rest. Here are seven such urban myths and legends.

Read on and retell, if you dare.

WARNING: Some of these myths and legends contain graphic details. Reader discretion is advised.

Michigan Triangle

The Michigan Triangle connects Ludington, Benton Harbor and Manitowoc, Wisconsin, over Lake Michigan, and much like the Bermuda Triangle, is an area infamous for shipwrecks, plane crashes, disappearances and other odd phenomena.

The first such incident occurred in 1679, when a French sailing ship, Le Griffon, disappeared and was never seen again. Over the next 344 years, many other ships, such as the Thomas Hume in 1891 and the Rosabelle in 1921, have been lost to the Michigan Triangle’s mysterious waters.

One of the most notable disappearances of the Michigan Triangle is Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 2501, which disappeared mid-flight on its way from New York to Seattle in 1950. After months of analyzing communication records and organizing searches, finding only body parts and debris no bigger than a human hand, the reason for the crash was labeled unknown. In all, 58 men, women, and children died in the crash, making it the largest loss of life in commercial aviation up to that point. To this day, the wreckage of Flight 2501 remains missing.

However, some of the most baffling stories are those of human disappearances. In 1937, Captain George R. Doner vanished from inside of his locked room aboard the O.S. McFarland. While assumptions of suicide or a sleep-deprived accident were made, Doner’s body was never recovered. Another disappearance was that of Steven Kubacki, a college student lost on a solo cross-country skiing trip in 1978. Kubacki reappeared over a year later, with no memory or awareness of the time he’d been away.

While much of the loss and damage can be explained by the destructive wind and waves of Lake Michigan, the Michigan Triangle brings into question where the natural and paranormal intersect.

More: 4 Michigan lakes among top 10 for swimming in America

More: Michigan's inland lakes: The deepest, largest and best

Nain Rouge

According to the myth, the Nain Rouge is a red dwarf or hobgoblin that appears to residents of Detroit as a precursor to tragedy, ushering bad luck and misfortune with him as he enters the city.

The first rumored appearance of the Nain Rouge was before Detroit’s founder, Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, who later was banished from the city, imprisoned, and lost his fortune before he died. The Nain Rouge also believed to have appeared before the Battle of Bloody Run in 1763, the 1967 Detroit riots, and a miserable ice storm that froze southeast Michigan in 1976.

Now, Detroiters celebrate the myth, hosting a parade every spring called the “Marche du Nain Rouge” — which is attended by protestors and supporters alike — to banish the Nain Rouge and ward off certain doom one more year.

While the community might celebrate the hobgoblin’s induction into Detroit culture, Detroiters must always keep watch for when the Nain Rouge returns and provokes disaster.

Dogman

One of the most famous urban myths known around the state is that of the Michigan Dogman: a dog-like creature that stands on its hindlegs at a height of seven feet — not to mention the torso of a human man and a howl that sounds like a human scream.

According to the legend, the Dogman appears once every decade of years, only on years ending in “7,” starting in 1887. While the Dogman is only known to leave paw prints and petrified witnesses behind, at least one person is rumored to have died of fright.

The myth gained popularity in 1987 when Steve Cook, a Traverse City radio station DJ, recorded a song about the Dogman as an April Fool’s Day prank. However, Cook was surprised to find there was fact in his fiction when his phone line was suddenly flooded with reports of Dogman sightings from all over the Great Lakes region.

Decades later, Dogman sightings continue, some of them “incredible stories from credible people” — as said by Cook himself.

Melon Heads of Saugatuck

Since the 1950s, residents and visitors of Saugatuck have been told to beware of the “Melon Heads” — small, bulbous-headed creatures with a hankering for violence.

There are multiple stories telling how the Melon Heads of Saugatuck came to be; the most popular is that they started off as children with hydrocephalus (water head syndrome) being treated by an evil doctor in a hospital near the Felt Mansion in Laketown Township. After enduring emotional and physical abuse, the children rebelled against the doctor, killing him — and according to some versions of the myth, eating him — before escaping into the woods. It’s now said that the Melon Heads reside in a system of caves and tunnels under Saugatuck, occasionally coming out of hiding to attack passersby.

While the true origin of the Melon Heads most likely has a much more mundane origin, walkers may want to stay suspicious of every twig-snap and leaf-rustle they hear when trekking the trails in southwest Michigan.

More: 10 of Michigan's most scenic hikes during the summer

More: Mysterious light draws thrill seekers to a U.P. forest

Singing Sands of Bete Grise

Bete Grise, found in the northern Upper Peninsula, is home to gorgeous lakeshores and tan beaches — as well as the mystical myth of their singing sands.

It is believed that the singing sands are what remains of a young Native American woman and her voice. After her lover drowned in Lake Superior, she stood on the shores and sang in hopes he would find his way back to her. She eventually withered to dust herself, but her songs remained in the sand, still calling out to lead her lost lover back to her.

The singing of the sand — which sounds more like a whistle or roar — is a natural phenomenon that occurs across the world, and can be man-made by visitors who rub or slap the sand between their hands. However, the Singing Sands of Bete Grise possess a unique supernatural quality: When visitors bottle up the sands and take them elsewhere, they refuse to sing.

More: Michigan gas prices hit high mark for 2023; 2 states now $5 or more a gallon

More: Michigan Democrats have seen big gains. That's no guarantee heading into 2024

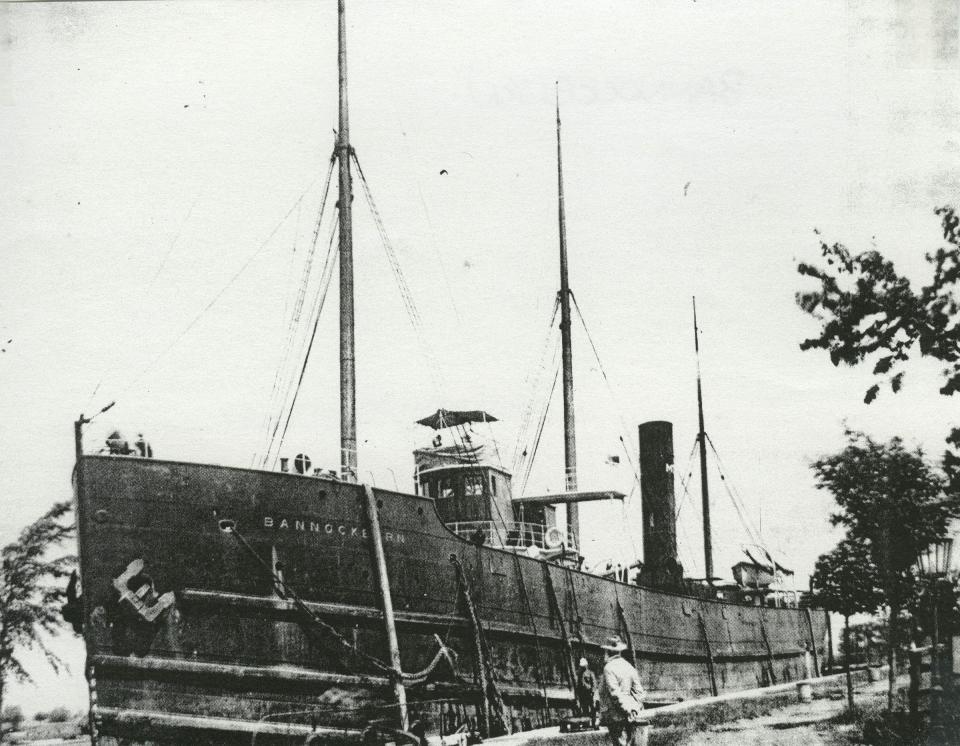

SS Bannockburn

Ghost ships aren’t just for the seven seas.

The SS Bannockburn was a steamship that disappeared on Lake Superior in 1902. It was last seen the day of its disappearance, when the ship was spotted by a crew member on another vessel. A winter storm hit later that night, and the SS Bannockburn was never seen again. No distress calls were made, no bodies were recovered, and to this day, no shipwreck has been found — only a sole life preserver that washed up on the shores of Lake Superior weeks after the disappearance.

Within the first year of the SS Bannockburn’s disappearance, it earned the title “The Flying Dutchman of the Great Lakes”. According to the stories, the steamship returns through the mist above Lake Superior as a ghost ship to warn people about treacherous conditions ahead. Some sailors trust the SS Bannockburn as a bad maritime omen, while others see the myth as nothing but a ghost of tragedy.

Hell’s Bridge

Perhaps the most frightening and gruesome Michigan urban myth of them all is Hell’s Bridge, a bridge in Rockford, haunted by the spirits of children and demons seeking to wreak havoc on others just as havoc was wreaked on them.

According to the legend, in the late 1800s, children from the town were going missing. The townspeople organized search parties in the forest to look for the missing children so they left their other children with a man too old to join in on the search, Elias Friske. While the townspeople were gone, Friske tied the children together with a rope, claiming that it would prevent anymore of them from getting lost. But then he led them into the forest, and as they ventured further, a horrid smell filled the air. The children asked Mr. Friske about the stench, and he then uncovered the rotting bodies of the missing children. As the children screamed, he killed them one-by-one and dumped their bodies into the Rogue River.

It didn’t take the townspeople long to realize that Friske and the children were missing. When they found Friske, he was covered in blood, repeating: “The devil made me do it.” The townspeople hung him off of a nearby bridge with the rope he’d used to tie the children together, and when the river swelled, it snapped the rope and whisked Friske’s body away.

Now, it’s believed that the evil spirits that possessed Friske along with the souls of the murdered children linger in the Rogue River, laughing, screaming and grabbing the feet of inner tubers as they float down the river, trying to drag them under the current.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: 7 famous urban legends in Michigan