Michigan woman had 350% interest rate on $1,200 loan — and a loophole allows it

DETROIT – Karl Swiger couldn't believe how his 20-something daughter somehow borrowed $1,200 online and got stuck with an annual interest rate of roughly 350%.

"When I heard about it, I thought you can get better rates from the Mafia," said Swiger, who runs a landscaping business. He only heard about the loan once his daughter needed help making the payments.

Yes, we're talking about a loan rate that's not 10%, not 20% but more than 300%.

"How the hell do you pay it off if you're broke? It's obscene," said Henry Baskin, the Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, attorney who was shocked when he first heard the story.

Baskin decided he'd try to take up the cause for Nicole Swiger, the daughter of Karl Swiger who cuts Baskin's lawn, as well as other struggling households caught in a painful debt trap.

Super-high interest loans should be illegal and several states have tried to put a stop to them through usury laws that set caps on interest rates, as well as requiring licensing of many operators. The cap on many types of loans, including installment loans, in Michigan is 25%, for example.

Yet critics say that states haven't done enough to eliminate the ludicrous loopholes that make these 300% to 400% loans readily available online at different spots like Plain Green, where Swiger obtained her loan.

Struggling with student loans?: You could be targeted by scammers

Fake credit repair scams: Consumers lose thousands to this scheme

How do they get away with triple-digit loans?

In a strange twist, several online lenders connect their operations with Native American tribes to severely limit any legal recourse. The various tribes aren't actually involved in financing the operations, critics say. Instead, critics say, outside players are using a relationship with the tribes to skirt consumer protection laws, including limits on interest rates and licensing requirements.

"It's really quite convoluted on purpose. They're (the lenders) trying to hide what they're doing," said Jay Speer, executive director of the Virginia Poverty Law Center, a nonprofit advocacy group that sued Think Finance over alleged illegal lending.

Some headway was made this summer. A Virginia settlement included a promise that three online lending companies with tribal ties would cancel debts for consumers and return $16.9 million to thousands of borrowers. The settlement reportedly affects 40,000 borrowers in Virginia alone. No wrongdoing was admitted.

Under the Virginia settlement, three companies under the Think Finance umbrella – Plain Green LLC, Great Plains Lending and MobiLoans LLC – agreed to repay borrowers the difference between what the firms collected and the limit set by states on rates than can be charged. Virginia has a 12% cap set by its usury law on rates with exceptions for some lenders, such as licensed payday lenders or those making car title loans who can charge higher rates.

In June, Texas-based Think Finance, which filed for bankruptcy in October 2017, agreed to cancel and pay back nearly $40 million in loans outstanding and originated by Plain Green.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau filed suit in November 2017 against Think Finance for its role in deceiving consumers into repaying loans that were not legally owed. Think Finance had already been accused in multiple federal lawsuits of being a predatory lender before its bankruptcy filing. Think Finance had accused a hedge fund, Victory Park Capital Advisors, of cutting off its access to cash and precipitating bankruptcy filing.

It's possible Swiger could receive some relief down the line if a class action status Baskin is seeking is approved, as would other consumers who borrowed at super-high rates with these online lenders.

"I don't know where this is going to end up," Baskin said.

Getting trapped in a loan you can't afford

Baskin said once he heard Nicole Swiger's plight he told her to stop making payments. She had already paid $1,170.75 for her $1,200 loan. The balance due: $1,922.

The online lender reported the stopped payments to credit agencies and Swiger's credit score was damaged. Baskin would hope that a resolution would include possible relief to her credit score. If this loan is deemed unlawful in Michigan, experts say, consumers could challenge it and tell the credit reporting agency to remove it.

It all started when Nicole Swiger, who lives in Westland, was sent an unsolicited mailing that told her that she could have $1,200 in her bank account the next day just by going online, according to the complaint filed in U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan in Detroit.

Swiger, who makes $11.50 an hour at Bates Hamburgers in Farmington Hills, Michigan, said she was struggling with an "astronomical car note," a bank account that hit a negative balance and worrying about making sure her 4-year-old son had a good Christmas.

Swiger, 27, needed money so she applied for the loan. Her first biweekly payment of $167.22 was due in December 2018. The loan's maturity date was April 2020.

Looking back, she said, she believes that online lenders should need to take into account someone's ability to repay that kind of a loan based on how much money you make and what other bills you pay on top of that.

Run the numbers if you're running scared

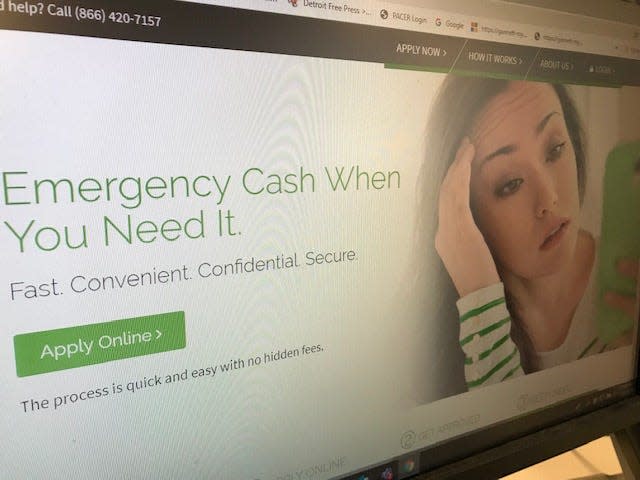

Plain Green – an online lending operation owned by the Chippewa Cree Tribe of the Rocky Boy’s Indian Reservation in Montana – markets itself as a source for "emergency cash lending." Its online site remained in operation in early July.

Plain Green is not a licensed lender in the state of Michigan, according to the Michigan Department of Insurance and Financial Services. But it is not required to be licensed as it is a tribally owned corporation.

In 2018, about 45,000 installment loans were made by licensed lenders in Michigan for a total of $699 million, with an average loan size of roughly $15,500. This number represents loan volume from Consumer Finance licensees; it does not include loans made by banks or credit unions. The numbers would not include lenders affiliated with American Indian tribes.

Plain Green says online that it has served more than one million customers since 2011. It posts testimonials on YouTube for its biweekly and monthly installment loans.

"I didn't have to jump through any hoops," one young man said in one such testimonial. "They didn't have to have to call my employer like some other places do. It was real easy."

If you go online, you can calculate your loan cost at the Plain Green site. Take out a $500 loan and you'll pay 438% in interest. You'd make 20 payments at $88.15 in biweekly payments. Pull out your own calculator to add up the payments and you'd discover that you're paying $1,763 for a $500 loan – or $1,263 in interest.

If you paid that loan off each month, instead of bi-weekly, you'd pay $1,910.10 – or $191.01 each month for 10 months. That ends up being $1,410.10 in interest.

The cost is outrageous but if you're in an emergency, you can talk yourself into thinking that maybe it will all work out.

Many of these online operators know how to market the loans – and play the game.

Consumer watchdogs and attorneys attempting to take legal action maintain that the tribal affiliation is but a scheme. Some go so far as to call it a "rent-a-tribe enterprise" that is established to declare sovereignty and evade federal banking and consumer finance laws, as well as state usury laws.

Nobody, of course, is going to a storefront in Montana or anywhere else to get one of these loans.

"These are all done over the internet," said Andrew Pizor, staff attorney for the National Consumer Law Center.

The strategy is that tribal sovereign immunity prohibits anyone but the federal government from suing a federally recognized American Indian tribe for damages or injunctive relief, Pizor said.

"Really, they're just sort of licensing the tribe's name," Pizor said.

So operators partner with a tribe, which may receive 4% or less of the revenue from the loans. But consumer watchdogs maintain that these are basically phony relationships where the tribe isn't really running the operations.

Another reason, Pizor said, that lenders have been able to get away with this strategy is that many of these lending contracts include arbitration clauses, which prevent most consumers from suing and arguing that they are protected under usury laws.

Baskin said Swiger's agreement had an arbitration clause, as well, but Baskin says it's not valid. Plain Green has maintained that “any dispute ... will be resolved by arbitration in accordance with Chippewa Cree tribal law.”

Baskin filed a class action complaint on July 8 in U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan in Detroit. Baskin's case involves suing individuals, including Kenneth E. Rees, who established Think Finance, as well as Joel Rosette, the chief executive officer of Plain Green. (Rees, currently the CEO of Elevate Credit, did not respond to an email from the Free Press. Emails and phone calls to Plain Green also were not returned.)

"I just want to shut this guy down in Michigan, at the very least," Baskin said.

Baskin said many times people who are struggling cannot afford to make such payments but they keep on making them to keep up their credit scores. Swiger said her score dropped nearly 100 points when she stopped making the payments.

"That's the hammer they use," he said. "You'll never be able to buy a car because we're going to kill your credit score."

While some settlements may be good news, consumer watchdogs say the fight will need to go on because online lending is profitable and the fight surrounding the sovereignty loopholes has gone on for several years already.

Consumers who get such offers are wise to take time to shop somewhere else – such as a credit union – for a better priced installment loan or other option.

"Consumers really should explore every other available alternative before taking a risky debt trap like this," said Christopher L. Peterson, director of financial services and senior fellow for the Consumer Federation of America.

Contact Susan Tompor at 313-222-8876 or stompor@freepress.com. Follow her on Twitter @tompor. Read more on business and sign up for our business newsletter.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Loan hits woman with 350% interest rate, and loophole allows it