Mid-Valley artist takes pride in ink, fish and citizen science

Richard Bunse’s brush sweeps the brow of a cutthroat trout swimming through his mind. Most nature artists work from specimens and photographs, but many of Bunse’s images emerge directly from memory. A lifetime artist, fly fisherman and conservationist, Bunse’s illustrations have appeared in America’s top sporting magazines and in over 30 books ranging from qigong and poetry to entomology and angling.

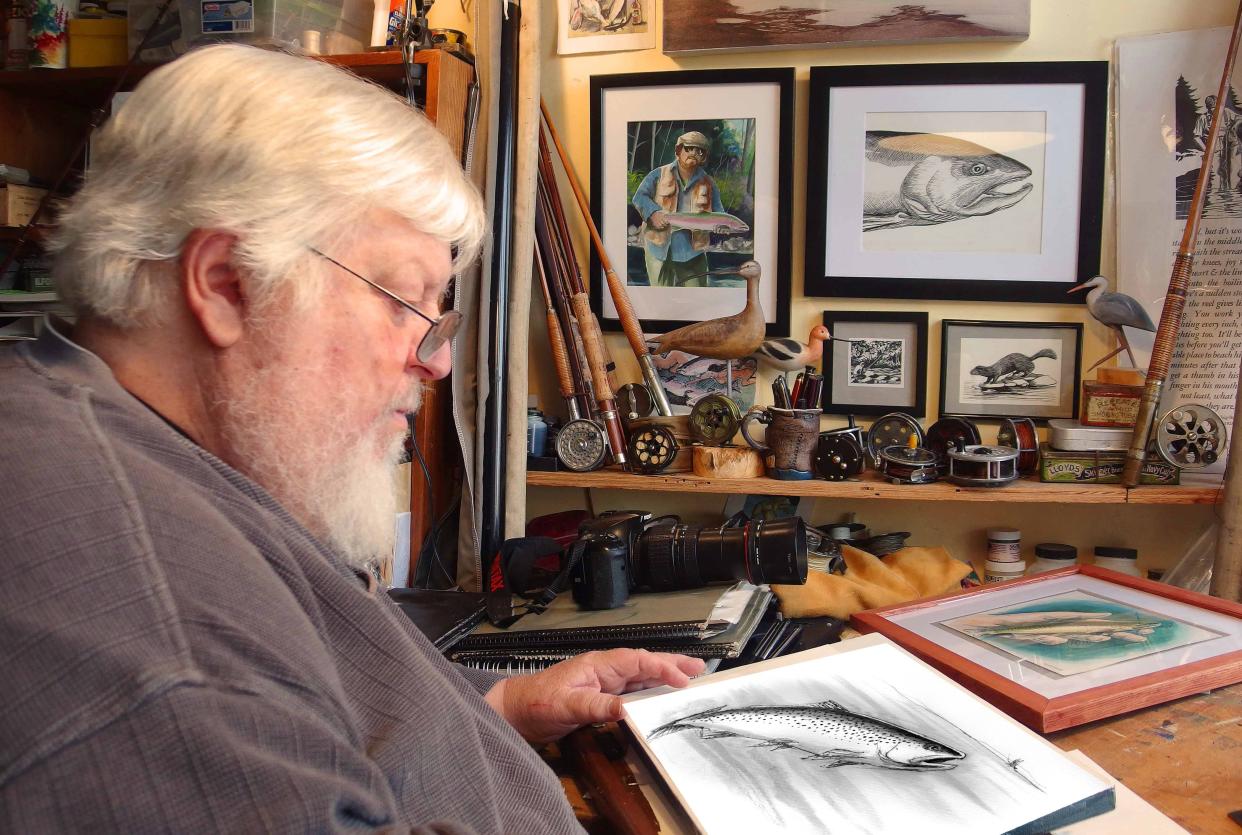

A soft spoken man with a crown of snow-white hair and a matching wooly beard, Bunse works from his Monmouth home studio. The sunlit room is packed-to-the-gills with books, antique fly gear, coffee cups, cookie dishes, art supplies and sketchbooks. An accomplished painter, photographer and illustrator, he’s partial to the ink wash technique bringing this cutthroat to life. A fountain pen lineates the rays of the dorsal fin, while a side-swept brushstroke shades the wide swoosh of the trout’s tail. The fish appears fully animated without the meticulous details of hyperrealism. “The economic ink wash can express so much with so little,” Bunse said.

A boyhood spent outdoors

Bunse spent countless hours as a youth splashing through creeks and rivers around his home in Salem, where he bonded early with the native cutthroat trout. “When the Pringle Creek got low in summer, I’d rescue stranded fish from pools, dumping them into the main flow.”

A boyhood of fishing, hunting and constantly sketching helped him survive high school. “I had undiagnosed dyslexia, which made reading difficult, and I barely got through school.” The disability, however, intensified Bunse’s visual abilities. “I learn about the world and express myself best through images.”

Two years after graduating from South Salem High School, he was drafted into the U.S. Army and served at a signal station near the Cambodian border during the Vietnam War. “One of the main things that kept me sane in Vietnam were thoughts of going back to my favorite creeks and rivers.” Returning home in 1969, Bunse fished “obsessively” for steelhead and trout in the Coast Range and Cascade mountains, and up and down the Willamette River. Between fishing trips, he tied flies and attended art and biology classes at Western Oregon University.

A focus on art and fishing

An affable man who loves to swap stories, in the early 1970s, Bunse met angling author Dave Hughes and the aquatic entomologist Rick Hafele. Admiring Bunse’s sketches, Hughes and Hafele asked the young artist to provide illustrations for a book project. Beginning in 1977, the three men, along with photographer Jim Schollmeyer, hiked, boated and waded all over Montana, Idaho and Oregon, fly fishing, tying and testing various flies, collecting specimens, and studying river life. Although Bunse’s ability to draw from memory and imagination was an asset, the use of specimens was necessary to achieve maximum anatomical fidelity. “This was before computerized magnification and projection,” Bunse said. “Rick would hand me vials filled with alcohol and twisted mayflies. I’d unfold the poor critters, hoping they were all intact, and put them under a microscope.”

Through a painstaking process of “looking and drawing,” Bunse produced portraits that impressed the authors. “Richard’s drawings were precise and alive,” Hafele said. “Wing venation can be the only way to distinguish certain species of mayfly, or mouthparts in the case of stoneflies, and he got it right.” The resulting "Complete Book of Western Hatches: An Angler's Entomology and Fly Pattern Field Guide," "An Angler’s Guide to Aquatic Insects and their Imitations" and "Western Mayfly Hatches from the Rockies to the Pacific" remain the most thorough and authoritative texts on the subject.

The meticulous work of scientific illustration took its toll, however. “A friend would call and ask what I was doing, and I’d say ‘drawing the anal hairs of midge larva,’” Bunse said, laughing and shakes his head. “Then I knew it was time to get out fishing.”

A love of steelhead

Steelhead, perhaps Oregon’s most prized gamefish, provided Bunse with another kind of fly fishing experience. “I first fished for steelhead in a remote canyon on the North Fork of the Siletz River — one of the most beautiful places on Earth.” Reflecting on the pristine habitat where steelhead thrive, Bunse recalls “seeing them in pools and tailouts. It was sight fishing and these big, gorgeous creatures made my heart throb.” When asked how he’d compare trout fishing to steelheading, he notes steelhead are not typically feeding, so it’s not a puzzle over hatches and rises, but rather how “an individual fish might react to a fly in different situations.”

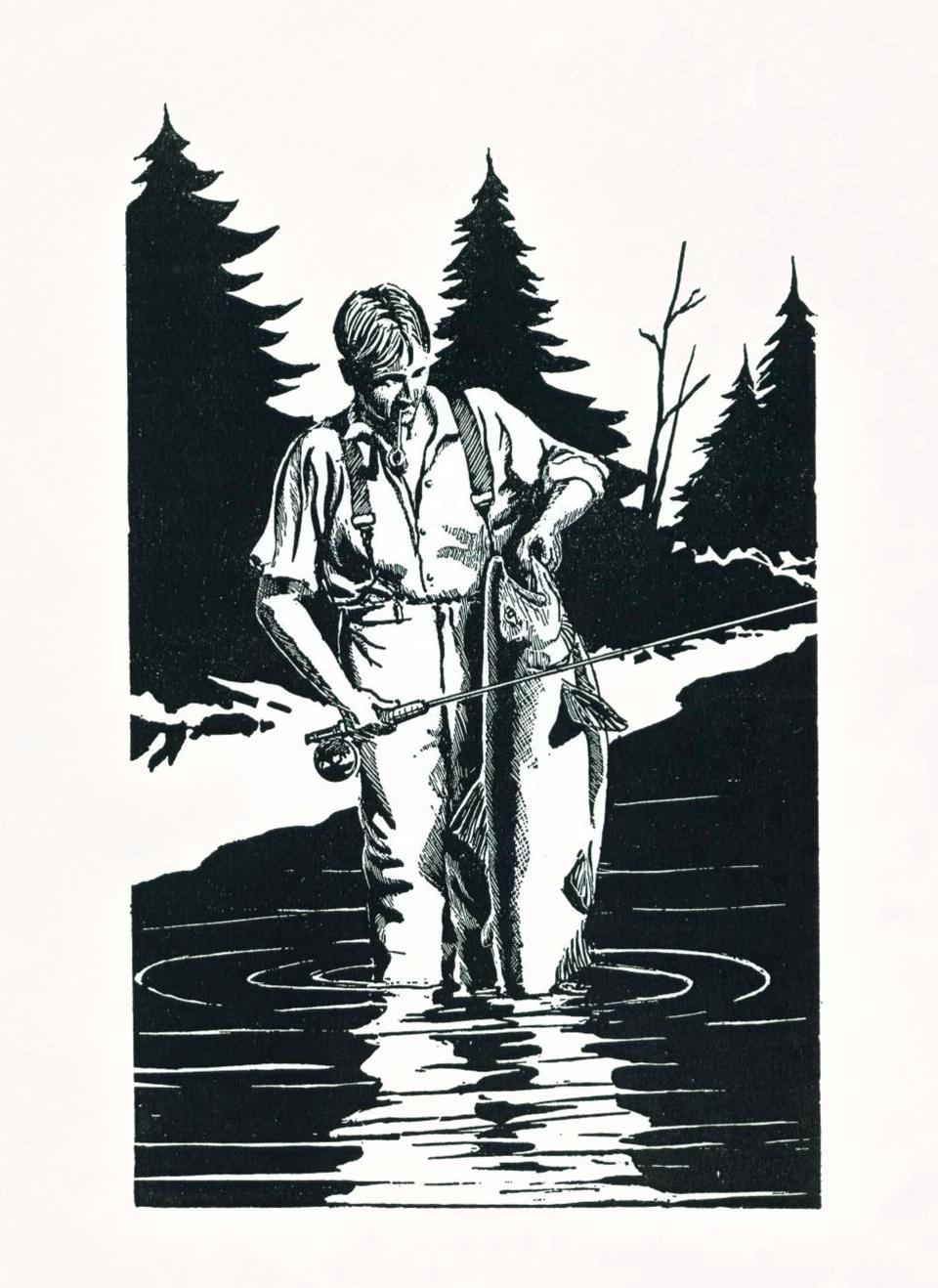

This love of steelhead drew Bunse to the work of the renowned Canadian author Roderick Haig-Brown. Once Bunse came to understand and manage his dyslexia, he enjoyed reading, especially Haig-Brown’s "Return to the River and Fisherman’s Fall." In the late 1980s, Bunse met Haig-Brown’s daughter, Valerie, who invited him to design and illustrate "The Diaries of Roderick Haig-Brown," written during the author’s early years in North America in the late 1920s and early ‘30s. Honoring the era and angling nostalgia evoked by this work, Bunse created clayboard engravings of fishermen and river wildlife. Similar to wood engravings, the resulting black and white images are crisp and representational, where the rippling reflection of an angler and his salmon complement the spirited prose.

Bunse pauses work on his cutthroat to pull "The Diaries" off a crammed shelf in his studio. Each individual book sports his paste paper monoprint cover as well as interior hand-colored illuminated initials celebrating the flora of Vancouver Island. “It took five years of challenging work,” he said. A limited letterpress edition of 175 copies were completed in 1992.

'The true trout of the West'

Cutthroat trout, named after the red slashes under their lower jaw, are native to the Pacific coast, Rocky Mountains and Great Basin. Asked why he's so drawn to the species, Bunse said “They’re hard to raise in hatcheries. We haven’t sent them around the world, like the rainbow. It’s the true trout of the West.” In addition to searun races, many cutthroat populations are potamodromous, moving many miles in and out of tributaries and rivers. “They are very adaptable,” Bunse said. Although he’s never finished a degree in art or biology, Bunse was consulted by the world’s leading expert on cutthroat trout, Patrick Trotter. While researching for "Cutthroat: Native Trout of the West," Trotter remembers spending “eight happy hours in a driftboat with Richard, a skilled fly fisherman who was very knowledgeable about rivers and trout — a true citizen scientist.”

True to the spirit of citizen science, Bunse helped found Oregon Trout in 1983. Working closely with national organizations, such as Trout Unlimited, and ultimately merging with The Freshwater Trust, Oregon Trout challenged government efforts in the 1980s to channelize streams and remove logs and other debris, theoretically to improve drainage and make more land available to agriculture, logging and development. “Ironically, they were straightening and clearing streams with federal funds set aside for conservation. People look back now and say those experts didn’t know any better. But we knew,” Bunse said. “As fly fishermen, we were up in those headwaters all the time," he said. "We knew what happened to streams when they were turned into drainage ditches.”

Another front in the battle to save wild trout arose over hatchery stocking programs. Although stream stocking was practiced widely in the western United States, Montana has completely stopped, and Oregon has severely limited the controversial practice. “Rivers like the Deschutes in eastern Oregon don’t need stocked fish,” Bunse said. “If it’s not overfished, a wild trout population will sustain itself.”

The spring-fed Metolius, a tributary of the Deschutes, is also stocked. With an average temperature of 48 degrees Fahrenheit the Metolius is frigid, but Bunse knew it held many wild fish. When anglers presented this information to the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, the agency invited Bunse and his associates to fly fish with a team of biologists in the off season. On a chilly February morning, the teams met up and the anglers landed several fish. The biologists took scale samples, measurements and notes. “Some of these guys couldn’t tell the wild fish from the tank-raised,” Bunse said. “It was obvious. The wild fish had pristine fins, not rubbed down, except under their tails — because some of them were spawning.” The state soon curtailed stocking the Metolius, which remains a wild trout, catch-and-release river with a robust population of native rainbows and bull trout. “People hated us,” Bunse admits. “But there’s plenty of nearby water where you can keep fish. The Metolius is a model for what wild trout water can be if you give it chance.”

A history of fly tying

Among the 100 or more fly patterns sold at the Metolius River’s Camp Sherman store, Bunse’s Green Drake Duns — “Wonder Duns” — remain one of the most popular. Rummaging through a dozen stained, battered and cracked fly boxes, he finds a Wonder Dun and holds it under a paint-splattered desk lamp. A complicated fly to tie, the sculpted Ethafoam mimics the body, and hairs from a deer hock make perfect upright comparadun wings for this buoyant and lifelike mayfly pattern.

Bunse first learned to tie flies from a ninth-grade teacher, and by the time he finished high school he was selling them to local shops. “I tied flies to save and make a little money, then I just did it for the joy and beauty of it.” Obtaining materials from ducks and pheasants he hunted, and from scavenged road kills, he participates in every stage of the craft. When Oregon’s rivers roiled high and muddy in February, Bunse would be tying up March Brown patterns. Hughes remembers fishing with Bunse in early spring. “He knew the March Brown hatch like no one else — Richard is one of the best dry fly fishermen I’ve ever known.” March is also a good time to find winter steelhead, and Bunse became enamored with the dazzling flies associated with that challenging pursuit, particularly the Spey flies created by Washington state master tier Syd Glasso. “They’re sexy,” Bunse said with a smile. Innovating on Glasso’s style, he created his own Rooster Spey, which uses hackle from pheasant, rather than heron, which are protected. Bunse’s admiration for Glasso culminated in his illustrated book, "The Syd Glasso Spey Flies."

The ink wash cutthroat trout is finished. Bunse holds up the paper to dry it, then hands it to me. Asked what kind of fly he would cast to the fish, Bunse smiles. “Oh, I’d just watch this one swim on by,” he said.

Henry Hughes is a professor of literature and writing at Western Oregon University.

This article originally appeared on Salem Statesman Journal: Mid-Valley artist takes pride in ink, fish and citizen science