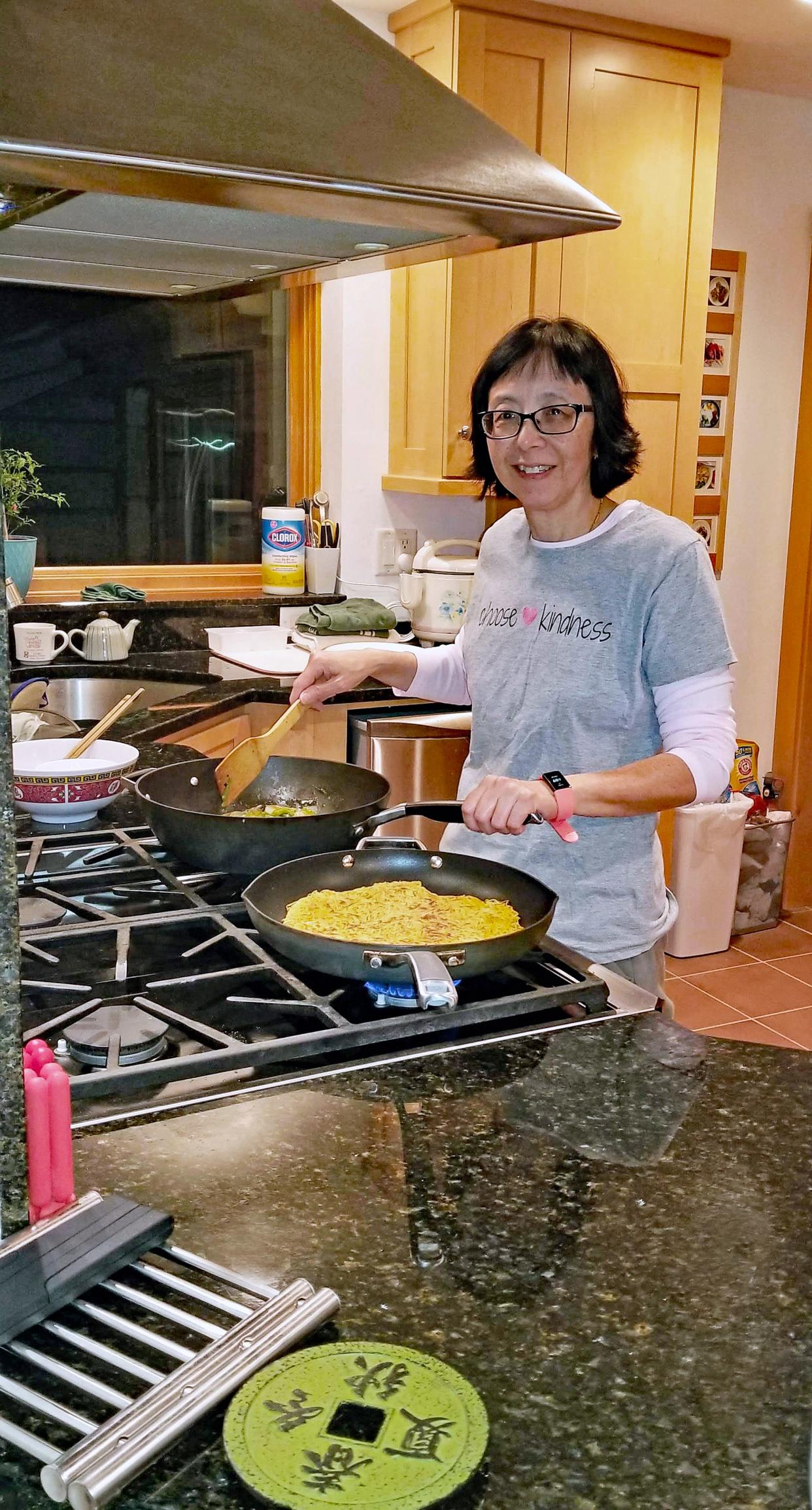

A midlife awakening to the family tradition of Cantonese cooking

I’ve never been much of a cook. My go-to meal is spaghetti out of a box smothered in jarred pasta sauce. Add some frozen meatballs and bake-at-home garlic bread to really make it special.

This culinary ineptitude is surprising, and disappointing, because both of my parents were terrific cooks.

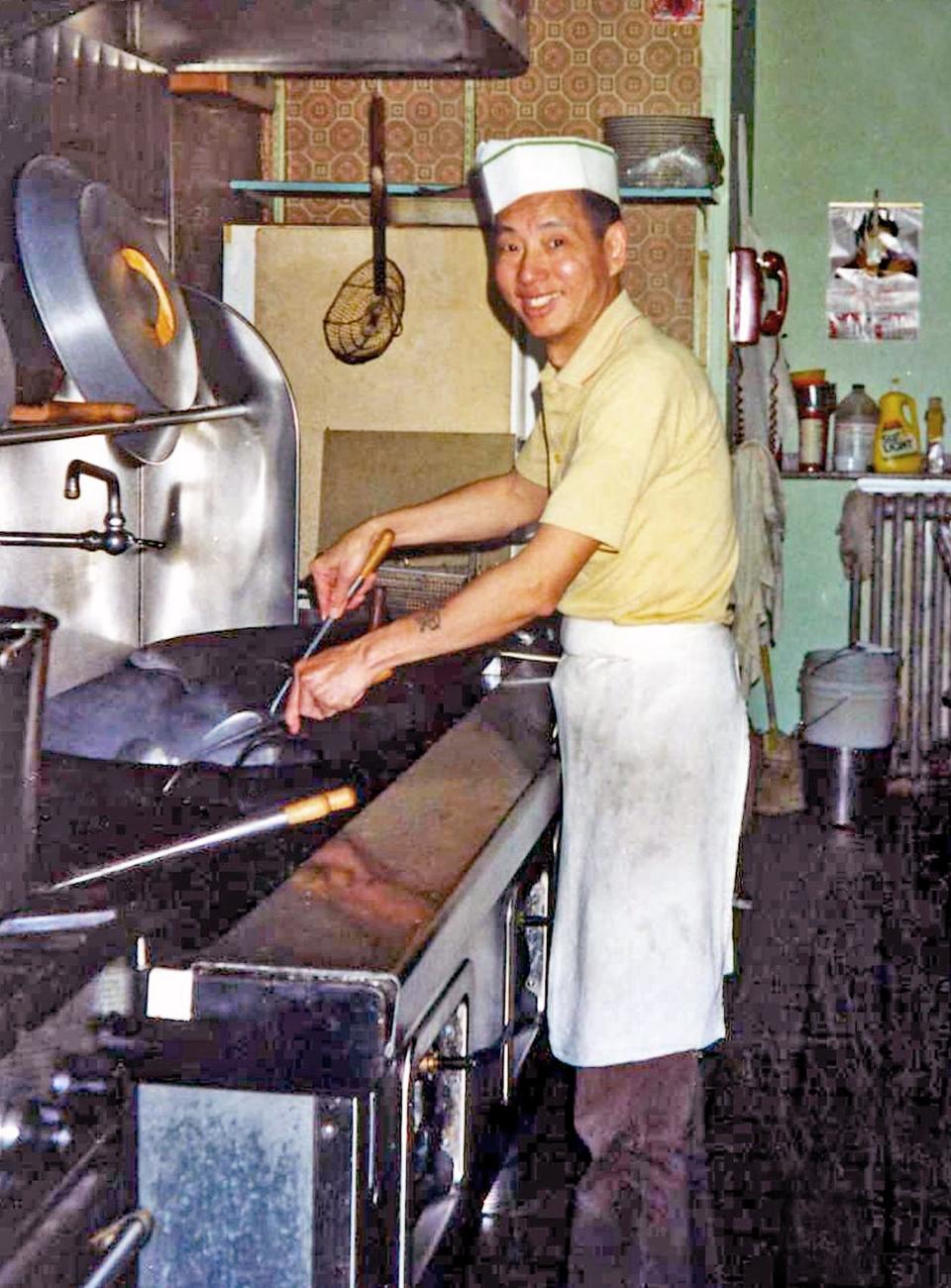

My dad, Fung (Tony) Wong, was a chef for three decades at Chinese-American restaurants in the metro area, including LaJoy’s and Silver Dragon in Milwaukee, Ming Garden in Shorewood and Paradise Gardens in Wauwatosa. He and my mom, Susie, owned and operated Chopsticks Restaurant at 54th and Center in Milwaukee for a decade before Dad retired in 1994. Mom also worked in the cafeteria at St. Joseph’s Hospital for nearly a quarter-century before she retired in 2003.

While Dad was a master of restaurant cuisine, Mom was the consummate at-home cook, preparing delectable comfort food for me and my three siblings growing up. Unfortunately, my parents’ skills in the kitchen never rubbed off on me.

I worked second shift for most of my 30-year newspaper career, so I was seldom home at dinnertime, which meant there wasn’t much opportunity or need to cook. My husband, Win, and I dined out — a lot. I’m talking several times a week, pre-pandemic.

While I can manage to put together a decent spread for the holidays or summer cookouts and I have a knack for baking desserts, preparing home-cooked meals on a regular basis isn’t something I ever had to do.

As is the custom with most Chinese parents, my folks cooked for me as an expression of love. This means that even when I was an adult, they prepared elaborate meals for me every Tuesday, providing me with enough yummy leftovers for the entire week.

On the rare occasion when I ran out of leftovers and craved Asian food, I’d throw together a simple meal of steamed egg, blanched iceberg lettuce drizzled with oyster sauce and boiled Chinese sausage served with rice. That was the extent of my “Chinese cooking.” I didn’t possess the skills, knowledge or motivation to venture into the daunting world of true Cantonese cooking.

That changed on March 15, 2020, when my dad passed away at age 90.

My parents had moved to an assisted living facility after Mom had a stroke in 2018. When Dad passed, the COVID-19 pandemic had just begun, and senior facilities shut down visits long term. We brought Mom to my home for her health, safety and happiness, and she has been living with me and my husband since.

I now had to figure out how to feed her healthy and tasty meals seven days a week. My awesome spaghetti dinners weren’t going to cut it. While Mom doesn’t mind Western food now and then, she really prefers Chinese food and wants to have it regularly.

So by necessity, I plunged headfirst into Chinese cooking.

First, it was simple meals made from memory, trying to replicate dishes that my folks made over the years. Things like pork congee (rice porridge) with preserved eggs, shrimp-stuffed peppers and crab omelets.

My parents cooked without using recipes, and Dad never wrote down or passed along any instructions. So the internet became my resource. I searched online for recipes of dishes that I wanted to make, scoured dozens of them and then cobbled together recipes that seemed to match the flavor of how my parents made the dishes. After tailoring the recipes to my specific tastes, I typed up instructions, printed them out and filed them in a burgeoning binder of Chinese recipes.

As my comfort level and confidence grew, I progressed to more challenging dishes like sweet and sour pork with sauce from scratch, shrimp with lobster sauce and seafood Cantonese chow mein. To avoid repeating meals week after week, I then expanded my repertoire from Chinese-American fare to authentic Cantonese and Hong Kong-style dishes. (My parents were born in the southern Chinese province of Guangdong, formerly known as Canton, and my siblings and I were born in Hong Kong. We immigrated to the United States in 1963.)

Some of these new attempts were dishes that Dad — a professional chef — had never even tried or mastered. Things like braised beef stew with tendon and daikon, beef rice noodle, crispy pork belly, barbecue roast pork and dim sum offerings such as steamed beef balls and stuffed Chinese eggplant.

I even tried my hand at making sweets, such as those served in Hong Kong dessert shops. Things like tofu fa pudding with ginger syrup, sweet potato and ginger soup, and steamed egg custard. And on my first try, I baked from scratch delicate almond cookies, far tastier than the store-bought ones offered at Chinese restaurants.

No longer intimidated and with a couple years of experience under my belt, I’ve set my sights on even more complicated dishes — roast duck, dim sum tripe, beef rice noodle rolls, steamed custard buns and Chinese fried dough, a cruller-like accompaniment to congee. Time is my only obstacle — caregiving and doing hours of rehab daily with Mom take precedence.

I’m fortunate that I’ve had many more successes than failures. But there, of course, have been hiccups along the way. On my first attempt at making pan-fried turnip cakes — a savory bite served in dim sum restaurants — I bought an absurdly oversized daikon. It yielded three times more shredded turnip than the recipe called for, so I frantically tripled the recipe.

That produced such a large batch of batter that I ended up with two humongous pans of the turnip cakes, which took more than two hours to steam. It was 3 a.m. by the time I finished, but it was worth the effort. They turned out perfectly.

It was a short-lived self-pat on the back, however, because the next time I used that recipe, the turnip cakes came out way too dense. So it’s back to dim sum training for me.

While I don’t have any recipes from Dad, I did inherit his trusty stainless steel wok (though I use a nonstick one for ease), a set of well-used cleavers and a cupboard’s worth of supplies. These include a gallon tin of Kikkoman soy sauce, home-dried tangerine peel, bean thread noodles, salted dried black beans, star anise, red fermented bean curd, five-spice powder and much more.

A couple of years ago, I wouldn’t have known what to do with most of those ingredients. Today, they’re staples in my pantry.

Mom no longer cooks because of physical limitations, but she has helped by sharing detailed instructions for some of her homey specialties, dishes like sticky rice with Chinese sausage, steamed pork patty with preserved cabbage, and steamed pork with homemade salted eggs. Her guidance has been invaluable.

To my astonishment, it turns out I have a pretty good palate and know how these dishes should taste and look. While I use recipes as a base, I cook completely by taste. Each time I make a dish, the measurements change (so different from the dessert baking that I’m used to). Doesn’t taste right? Add a splash more oyster sauce. Still not good? Stir in another spoonful of fermented black beans.

No one is more surprised by, and pleased with, my newfound culinary abilities than my mom. Her eyes gleam when I serve her a favorite dish. And when I clear her plate after a particularly good meal, she smiles and says in Cantonese, “ho mei,” which means delicious or good flavor. On those days, I know I’ve done well.

Last year, Mom offered me the highest praise by telling me that I’m a better cook than even Dad. I was floored. Anyone who’s ever had the pleasure of tasting my dad’s cooking would know what a compliment that is.

Today, when I’m preparing one of Dad’s specialties, like his soy sauce chicken wings, ketchup shrimp or braised chicken with potatoes, I feel such a sense of accomplishment. How amazing it is that I’ve created a dish that tastes just like ones that he — this phenomenal chef — made.

I have no explanation for how I went from essentially being a non-cook to becoming a somewhat accomplished chef of Chinese food in such a short time. Was it osmosis? All those hours spent as a child hanging out in the kitchen while my folks prepared dinner? Or the 10 years I manned the lunch shift at their restaurant while Mom worked her day job at St. Joe’s, watching Dad expertly make egg rolls, pressed duck and sweet and sour chicken?

That could be, but I feel that Dad somehow has a hand in my success — that I’m channeling him. There are times when I’m prepping vegetables for the next day in the wee hours, and I’m thinking of him. I’ll hear an inexplicabIe noise in the dead-quiet kitchen, and I know it’s him. It doesn’t alarm me. I just say, “Hi, Dad. Miss you,” and continue chopping away.

In March, it’ll be three years since Dad passed, which is when my unexpected, late-in-life journey into Chinese cooking began. Some of the ingredients that he left behind are still in my cupboards. But little by little, day by day, I’m using them up.

That makes me sad because those tangible connections to Dad are disappearing. But at the same time, I think it makes him happy to see me cooking as he did, especially for Mom. I hope it also makes him proud.

Mabel Wong of Brookfield is a freelance editor who for three decades worked at the Milwaukee Sentinel and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, most recently as the Editorial Board’s Perspectives editor.

*****

The dark soy sauce this recipe calls for is sweeter and a little thicker than regular soy sauce and is used to impart color in addition to flavor. It is found at Chinese and other Asian grocery stores, as is the rock candy, or crystallized sugar. The rock candy can be found in the spice aisle.

Soy sauce chicken wings

Makes about 3 servings

7 to 9 chicken wings, tips removed (can be left whole or cut in half)

4 slices gingerroot, cut into ¼-inch-thick coins

2 green onions, cut into 2-inch pieces

Braising liquid:

1 cup water

½ cup soy sauce, such as Kikkoman

¼ cup dark soy sauce, such as Lee Kum Kee brand

1½ tablespoons oyster sauce

½ cup rock candy, or crystallized sugar, such as Yong Long brand

3 star anise

2 bay leaves

In a stockpot, add enough water to cover the wings. Remove wings to a bowl before bringing water to a boil. Add ginger and green onion to boiling water. Cook for 30 seconds. Add the wings. After the water returns to a boil, cook for 3 minutes.

Remove the wings to large bowl of ice water (to firm up the skin) until fully cooled. Drain. Discard the ginger and green onion.

Meanwhile, as the wings cool, combine all the braising-liquid ingredients in a Dutch oven or clean stockpot over medium to medium-high heat and heat until the rock candy dissolves. Taste and adjust as needed. It should be sweet and plenty salty.

Add the wings to the stockpot. Raise heat to high. After the liquid comes to a boil, reduce heat to bring to simmer and cook uncovered for about 20 minutes. With a wooden spoon or chopsticks (to avoid tearing the skin), turn wings occasionally to coat evenly. The skin should turn a nice dark brown.

Serve over rice, along with some of the braising liquid as a sauce.

The braising liquid can be reused over and over. After it is slightly cooled, strain through a sieve into a large measuring cup. Pour into a large glass jar. Refrigerate overnight. Skim off the fat and discard, and freeze the braising liquid. To reuse, thaw in refrigerator for a day. You can add more soy sauce, rock candy, anise and bay leaves to boost the flavor.

Sign up for our Dish newsletter to get food and dining news delivered to your inbox.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Chinese food is her heritage. She went decades before exploring it