A Milestone for the National Trust for Historic Preservation

“In preservation there’s a 50-year rule, so our work is about historic cultural heritage, but this is an opportunity where we are expanding what it means to evaluate and to commemorate historic and contemporary events,” Brent Leggs, executive director of the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund says, referring to the $50,000 special gift the Action Fund is giving to the city of Minneapolis’s historic preservation office. “After the horrific killing of George Floyd, we realized there was an opportunity to make the connection between preservation, history, and this kind of injustice that impacts Black communities across the country,” Leggs tells AD.

The special gift to Minneapolis represents the first time the National Trust is giving a grant to preserve contemporary history. It was a late addition to the list of 27 grantees being awarded $1.6 million this year. Since its founding in 2017, the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund—whose mission is to preserve Black historic sites across the U.S.—has invested $4.3 million in 60 preservation projects.

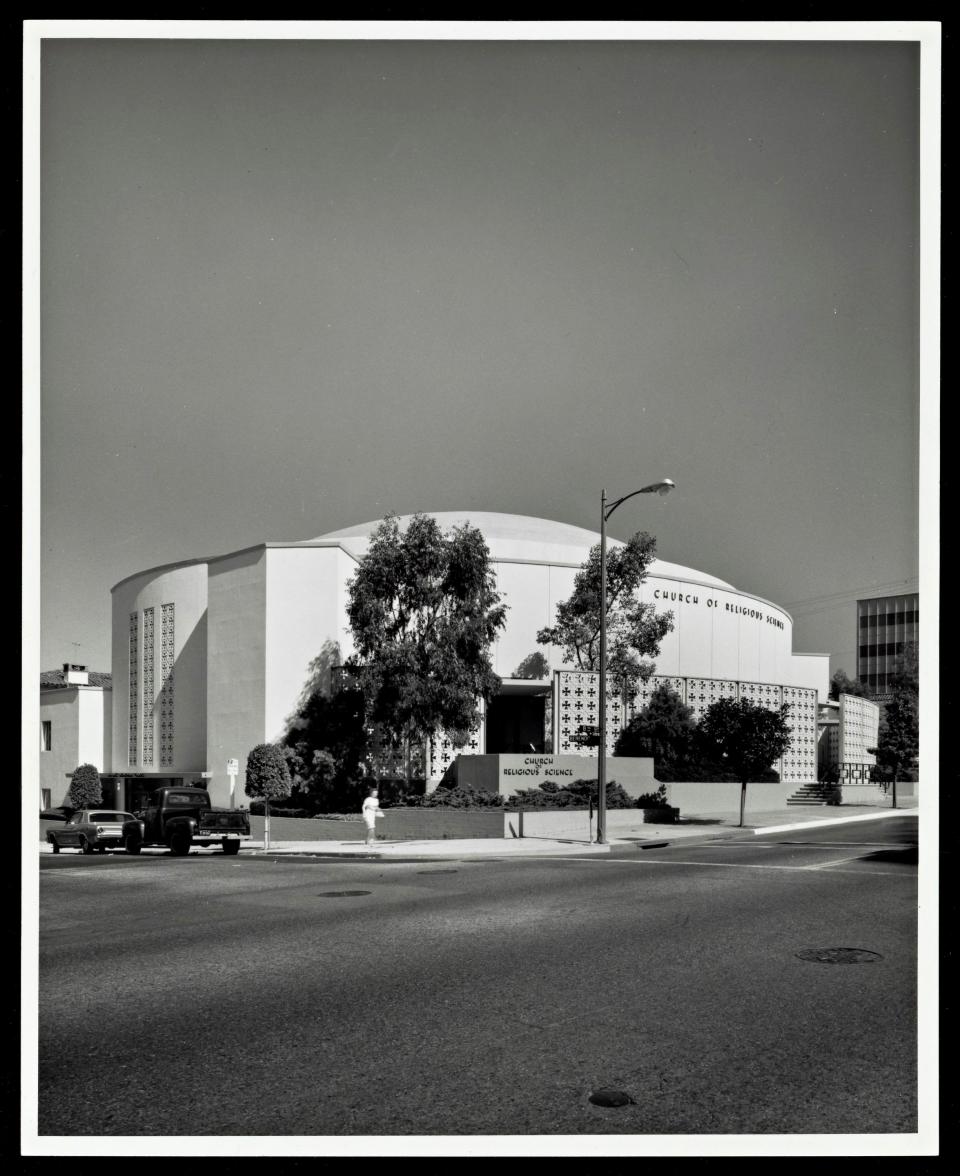

The Action Fund has just announced its 2020 grantees today, and they’re a diverse group of sites and organizations that commemorate African American contributions to architecture, the arts, music, science, entrepreneurship, and civil rights. There’s the Founders Church of Religious Science designed by trailblazing architect Paul R. Williams, the first Black member of the American Institute of Architects, whose contributions to Los Angeles’s landscape include the Beverly Hills Hotel, the Theme building at LAX, and the homes of many Hollywood stars. “The landscape of Los Angeles was once filled with his designs,” Leggs says. “And unfortunately, over time the loss and erasure of many of these places has happened, but Founders Church stands to exemplify the brilliance of his mind and his creativity.”

gri_2004_r_10_b308_f20_003

There’s the Philadelphia home of singer and actor Paul Robeson, who in 1925 became famous for his performance in Show Boat; the Baltimore home of poet Lucille Clifton, who was the state of Maryland’s poet laureate from 1974 until 1985; and the Chicago home of musician Muddy Waters, known as the father of modern Chicago blues. “The influence of African Americans in arts and culture is known nationally and internationally, and we’re excited to be able to recognize sites of arts and culture like Muddy Waters’s house in Chicago or bring greater recognition to an acclaimed and under-recognized poet, Lucille Clifton, and her mastery of the use of words and creativity that’s expressed through her art,” Leggs continues.

The grants also commemorate the loss and destruction of Black heritage in the United States. A grant to the Historic Mitchelville Freedom Park in Hilton Head, South Carolina, aims to support new archeological research on the site of the first self-governed, self-sustaining African American community post-emancipation. “It tells this unique story of what some of the first Black architecture looked like and landscapes and spaces where African Americans were free and were creating their own way in a new America at that time,” Leggs—who has visited the site—says. “There’s something haunting about the landscape and the trees and there is beauty in that haunting. To walk those grounds and to hear the tour guides bring life to the story is powerful, and for me it felt like a journey I was on to rediscover the founding of Black freedom in the United States.”

This year’s largest grant goes to a place whose story has gained attention during the recent Black Lives Matter movement: the Historic Vernon A.M.E. Church in Tulsa, Oklahoma. This church is the last remnant in Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood—once known as Black Wall Street—that survived the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921. In preparation for its 100th anniversary, the Action Fund is awarding $150,000 to the church for the restoration of its stained glass windows. “The social fabric of that community was devastated and destroyed because of racism,” Leggs says. “We believe that preservation is a form of repair to memorialize the injustice that happened there, but also to continue to revitalize the once thriving center of Black life in Oklahoma.”

While the Action Fund has made incredible strides in its mission to preserve Black historic places, there’s still a long way to go. “The gap is significant and our nation needs to catch up. With urgency and intention, I encourage the nation to invest in the preservation of this part of our history,” Leggs says. “We can use this moment to repair the injustices of the past and celebrate our nation’s rich, complex American story.”

Originally Appeared on Architectural Digest