Millions of dollars coming to Idaho to fight opioid epidemic. Where is money going? | Opinion

Editor’s note: This is the first in a series about how Idaho plans to spend millions in opioid settlement funds.

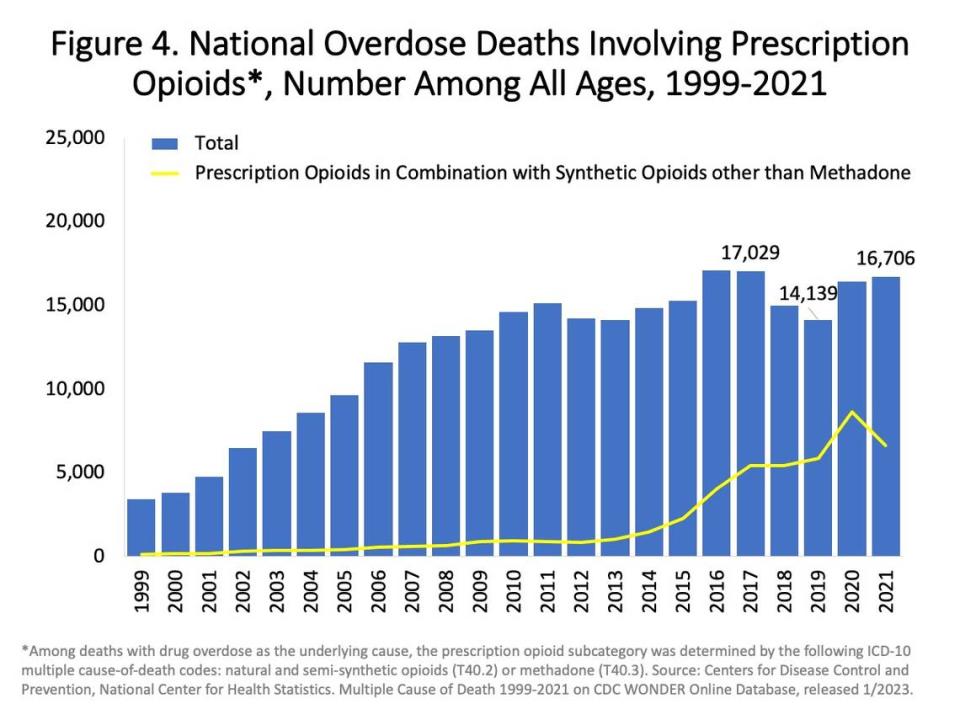

Idaho is expected to receive at least $218 million over the next 18 years in settlements with opioid manufacturers and distributors, money that can be used to repair the damage done by the flood of opioids into our state.

It’s part of national opioid settlements totaling $54 billion, with such companies as Johnson & Johnson, AmerisourceBergen and McKesson.

At first blush, it may seem like a lot of money, but the way the money is rolling out and being spent, it’s questionable how much it really will help.

The money is so spread out among the state, counties, cities and public health districts, it’s like a garden hose set on mist. And once the money trickles down to everyone, the amounts can be so small, its effectiveness is questionable.

For example, Southwest District Health expects to receive no less than $3.2 million in opioid settlement funds – over the next 16 years. It gets some money upfront, but on average, that’s just $200,000 a year. The district’s total annual budget, by comparison, is about $11 million.

“There’s a perception that there’s like $80 million sitting in a fund that can be spent, and that’s not accurate,” Sara Omundson, co-chair of the Idaho Behavioral Health Council, told me in a phone interview. “That’s not how it has played out.“

Further, the list of eligible uses is so long and broad — more than 12 pages of 100 categories of eligible uses — agencies can spend it on any number of projects, including renovating a courthouse building.

That raises the question of whether the opioid settlement funds will become like tobacco settlement funds, which have been misspent nationwide on uses other than smoking prevention programs.

Idaho opioid funds

Of the settlement money, 40% goes to the state government; 40% is shared by all 44 counties and several cities; and the remaining 20% will be shared among the state’s seven public health districts.

For the state’s share of the settlement, the Idaho Legislature in 2021 directed the Idaho Behavioral Health Council to make recommendations on how to spend the money.

But so far, the Behavioral Health Council has made only broad, general recommendations without specific direction or dollar amounts:

one-time funding for housing initiatives

ongoing funding for community recovery centers

one-time pilot pre-plea intervention program

one-time pilot low-risk/high-need treatment court or track within existing treatment court

inpatient detox and treatment

Of the council’s recommendations, just two items funded by the opioid settlement fund made it into the governor’s budget and through the Idaho Legislature last session: $286,500 for a pilot pre-plea intervention program and $104,300 to pilot a low-risk/high-need treatment court or track within the existing treatment court.

The largest expenditure wasn’t even recommended by the council: $500,000 for the Idaho State Police interdiction team to increase drug seizures.

Even though it’s in the statute that the Behavioral Health Council is supposed to recommend how the money should be used, that’s not what’s happening.

“I don’t have the sense that we’ve had a specific focus on spending that money,” Dr. David Pate, who’s been on the council since it was created, said in a phone interview.

Granted, part of the reason for the lack of specificity last year was the council didn’t know at the time exactly how much money was going to be available, according to Omundson, who is also Idaho’s administrative director of courts.

“We didn’t ask for dollar amounts, in part because last July, we didn’t know how many dollars there were going to be available,” Omundson said. “We asked for high-level recommendations: Where should the state invest?”

And it sounds like the council, even though it should have a better idea this year of how much money will be available, won’t be focused on the money or how it should be spent.

“I do think over time, we’ll get more and more specific about those topics, but we really don’t intend to give dollar amounts out of (the council),” Idaho Department of Health and Welfare director Dave Jeppesen said in a video interview. “We will hand that back to the agencies that are accountable for those things.”

So who’s in charge of watching those settlement funds as they come in, what’s available and how they get spent?

Eligible uses of opioid settlement funds

Agencies using settlement funds are required to file an annual report that includes an accounting of how the money was spent and documenting which categories the spending falls under.

But the 12-page list of eligible uses, as set by the terms of the settlements, is a broad range of more than 100 items that include direct treatment, support for people in treatment and recovery, helping those in the criminal justice system, even leadership, training and research efforts related to opioids.

Ada County has received $1.2 million from the opioid settlement so far, according to Elizabeth Duncan, communications manager for the county. All the money will go toward renovating a building on Elder Street and moving Ada County’s Drug Court program from Benjamin Lane there.

“Based on the fact that it’s an opioid fund settlement, the most appropriate use for it from a county perspective would be a program that saves the county millions of dollars and that saves so many lives, and it’s all focused on drug use,” Duncan said.

The renovation of the building will allow the county to house the courtroom along with counselors and a drug testing facility, so that it becomes a one-stop shop for drug court participants, making it easier to successfully complete the program, according to Duncan.

By contrast, Central District Health is planning to use the $1.5 million it’s received so far on direct treatment and prevention, according to Rebecca Sprague, health policy and promotion manager at Central District Health.

In addition to a prevention program for youth, CDH is also using opioid settlement funds on a medication-assisted treatment program that uses medications, counseling and behavioral therapies to treat people for opioid use disorder, and hopefully get them to a point where they’re in long-term recovery, Sprague said.

In Canyon County, plans are in the works for a new 20,000-square-foot youth behavioral health community crisis center. The city of Nampa has committed $150,000 of its approximate $300,000 in opioid settlement funding, and Southwest District Health has committed up to $500,000 in opioid settlement funding toward the center, slated to open in early 2024.

Mistakes of the tobacco settlement

With such a broad list of eligible uses, the opioid settlement funds run the risk of making the same mistakes as misspending money from the 1995 tobacco settlement.

The Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids each year monitors whether the states are using a significant portion of their tobacco settlement funds — estimated at $246 billion over the first 25 years — to attack public health problems caused by tobacco use in the United States.

In the current budget year, the states will collect $26.7 billion from the tobacco settlement and taxes, but they will spend just 2.7% of it — $733.1 million — on tobacco prevention and cessation programs, according to the campaign.

Idaho last year received $22 million from tobacco companies but spent only an estimated $4.4 million on tobacco prevention programs, according to the campaign. That pales in comparison to the estimated $50 million tobacco companies spent marketing in the state.

Without specific prohibitions on what entities can spend money on, the opioid settlement funds run the risk of similarly becoming simply a slush fund in government general funds.

The opioid settlements were expected to be a boon to the states to help clean up the mess that opioid manufacturers and distributors left in their wake.

Unfortunately, the way the money is rolling out and being spent and the lack of a coordinated effort, it’s questionable just how much good it’s really going to do.