Milwaukee bar owner has been stuck in his home for 11 days due to broken wheelchair lift

Dressed in a pair of shorts and a light jacket, 69-year-old Jewel Currie sat outside of his bar, Garfield's 502, on Nov. 22, waiting for assistance. A Green Bay Packers blanket was draped over his waist to keep him warm in the biting November cold.

Currie had just returned from an afternoon doctor’s appointment. But when his nephew pushed the button for Currie’s wheelchair lift, they were greeted by a scraping sound coming from the gears. Despite their efforts to revive it, the machine remained stuck.

Currie, who was partially paralyzed five years ago after breaking his neck in a fall, had the Savaria outdoor wheelchair lift installed in 2018 by Access, a Wisconsin company specializing in assistive living technology.

Currie said Access sent an employee to check the system that afternoon, but they left without providing an update.

It was 9 p.m. when Currie decided he wouldn't wait any longer for the lift to be fixed. He enlisted four of his regular customers to grab him by his arms and legs to heave him up the 19 steps to his apartment. They settled Currie — 6'8" and just over 200 pounds — into bed, accepted his thanks and left him to rest.

Currie remained in his bed on Thanksgiving Day. Eleven days later, he remains trapped there, with no guarantee of when his wheelchair lift will work again, Currie's nurse Demetrice Owens told the Public Investigator team.

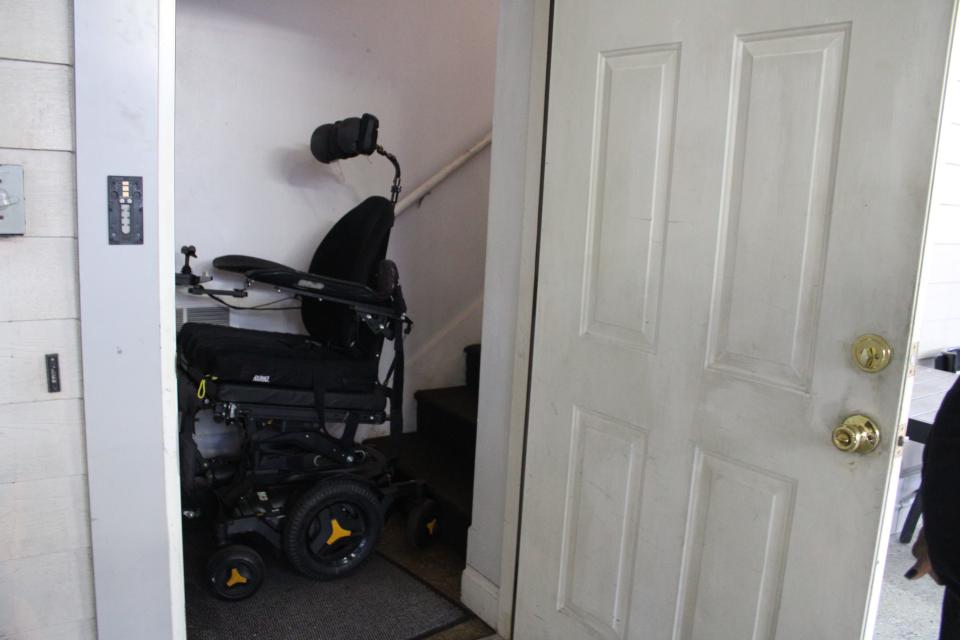

His nearly 400-pound electric wheelchair remains wedged between the door and stairs, squeezed tightly in the entryway.

"I'm in a lot of pain," said Currie, who has little use of his hands and cannot get out of bed on his own, due to his injury. "The difference with the chair is that I can recline the chair in different positions, take the pressure off my back and shift my weight to other parts of my body. Laying in bed all day, I have to have someone roll me from side to side."

Multiple times a week, Owens visits Currie to tend to his healthcare needs: checking his IVs, bathing him, trying to prevent bedsores, and making calls to local contractors who might be able to fix the lift.

Owens decided to advocate for Currie after what she described as a lackluster response from Access. She described phone calls in which Access employees told her that all their customers had disabilities, and they would try to get someone out when they could.

"To me, it's like, they show no empathy, no compassion. It's just, 'Well, we'll get somebody out there when we can,'" Owens said.

By Monday, she had called Access 11 times about Currie's troubles.

Wheelchair lift company blames delay in shipping parts

The Journal Sentinel reached out to Access last week to ask owner John Tevz about the status of Currie's lift repair.

Tevz said an examination of Currie's lift revealed that the lift's circuit board died. He said delays in the shipment of the replacement parts nationwide make fixing specialized machinery like Currie's more challenging. The product is being shipped from Canada by the manufacturer and could take up to a week and a half to arrive, according to Tevz.

Tevz said his company has been in communication with Currie and expressed frustration about Currie reaching out to the media organization.

"Now it feels like he doesn't think we are trying to service him, lying to him or not taking care of it intentionally," Tevz said. "That is not the case. And to know that he's gone this route is kind of disappointing because we were doing our best."

Tevz said an Access technician would head to Currie's promptly to fix the lift when the new circuit board arrives.

"We take every service call seriously, but there's some things that are out of our control," Tevz said. "You're calling after hours during the holidays. Our manufacturers are closed, so we knew we couldn't get tech support anyway."

Tevz also pointed to Currie's lack of a lift servicing contract as a reason for the lift breaking down. According to Tevz, the company has pushed Currie to acquire an annual servicing contract, meaning an employee will come back quarterly to check for mechanical issues and, if needed, change the system's oil.

The annual cost for the service is about $800 per year, a cost that Tevz said puts off many customers.

"It's just kind of an industry problem, but we just gotta deal with it," he said. "Everybody gets told about this service."

Currie said he will request a contract as soon as the lift is working again. But while he waits for his lift's fix, Currie has few ideas for how he will navigate getting to his cardiology and physical therapy appointments.

Tevz said though he could understand Currie's tough circumstances, he and his team are not allowed to lift and carry people.

"They always have 911," he said. "I know people don't like to do it, but, if somebody's stuck on a lift, we can't do anything."

More: Our Public Investigator team wants to solve your problems

Joshua Parish, assistant chief of the Milwaukee Fire Department support bureau, warned that requests like Currie's to be carried up and down the stairs might not be considered urgent. Private EMT services, he said, are a better option.

However, a national EMT shortage has also made accessing private ambulance companies harder in recent years. In Milwaukee, much of the city relies on just two companies: Bell Ambulance and Curtis Ambulance. Both companies field hundreds of calls per week and are required to prioritize life-threatening situations over lift assistance.

According to Scott Mickelsen, director of client services at Bell Ambulance, what Currie needs — a basic life support ambulance without transfer to a hospital — can cost between $300 to $500 per visit.

Delays in assistive technology repair reflect a broader national shortage

Disability rights advocates and independent living organizations said Currie's experience is not unlike that of many other disabled people who often find themselves stuck in apartment buildings, offices and other public spaces as a consequence of faulty assistive technology and nationwide shortages of replacement parts.

According to a November report by the National Disability Rights Network, the durable medical equipment industry is facing a variety of challenges, including supply chain disruptions.

The products being most directly impacted by these delays include wheelchairs and other mobility aids, respiratory equipment, and other equipment used to manage chronic health conditions or disabilities. Assistive mobility technology like Currie's lift face similar delays.

Experts say the delay in repairs began during the COVID-19 pandemic and has since worsened. Like Currie, individuals needing repairs to a broken lift or a faulty wheelchair are waiting weeks or even months for a contractor to obtain the necessary parts to fix the technology.

The challenges persist on both a local and national scale, advocates said.

Looking for an alternative to Access, Currie's family members and Owens called seven accessible technology contractors to see if they could repair the lift. Their responses were the same: The parts needed to fix the machine were on backorder, and repairs could take up to three weeks.

The Journal Sentinel contacted Savaria, the manufacturer of Currie's wheelchair lift, to ask about the delay in getting the replacement circuit board.

Allan Thompson, Savaria's director of sales, said in most situations, replacement shipments take at least a few days with shipping, sourcing and testing the product before it is delivered to a contractor.

"I have spoken with my team at the factory and asked them to locate this order to make sure that we were doing everything we can to get this fixed," Thompson said. "It's not a good situation when a lift is down and we'll do our best to do it to push out parts and get this repair done."

Amy Scherer, a staff attorney at National Disability Rights Network, said making manufacturers and repairers understand the daily burden of technology being broken can be a major challenge.

"Sometimes the perception is that disabled people have nowhere to go or nothing to do. We all just kind of hang out in our apartment and watch movies," Scherer said. "If your wheelchair is broken, it may impact your ability to get out of bed, take a shower or even do anything around your apartment."

Over the last year, 16 states have considered implementing "right to repair legislation," which pushes assistive equipment and durable technology manufacturers to make it easier to find replacement parts and make repairs, and in some cases, even requires companies to make fixes within a certain timeframe.

Repeated problems with faulty technology can lead to an otherwise independent person getting seriously hurt or being forced into a nursing home, said Gerald Hay, director of Independence First, a Milwaukee-based disability advocacy organization. That's an expensive outcome that many of the organization's clients try to avoid, he added.

"The difference in the cost to put somebody into a home for $25,000 a month as opposed to $500 to get a lift repaired — the savings are huge," Hay said.

The wait continues

On Thursday, Currie had an appointment he couldn't miss. His Milwaukee County paratransit license expired at the beginning of the month, meaning that the large white van that usually took him to doctor's appointments each week no longer showed up at his door.

At 11 a.m., he needed to be at his in-person license renewal interview.

A cohort of Currie's friends gathered in front of Garfield's 502. They planned to place him in a temporary, non-electric wheelchair and carry him down the steps.

With a white-knuckled grip on the chair's handlebars, two men navigated their way down to the ground level from the second floor while Currie's nephew guided the chair from above. All three used the walls to support their weight, tilting Currie back at a 45-degree angle.

When asked if he felt safe on the trip down the steps, Currie replied, "I felt okay. Didn't want them to drop me." He paused. "This is pretty screwed up."

As he waited in the bar for his ride service to arrive, his nephew wiped his face with a warm towel.

"I gotta get a haircut," Currie said between sighs. "Haven't seen anybody other than my nurses until today."

A few hours later, Currie returned to his bed, transit interview all finished. His friends carried him back up to the apartment while the bar below continued to run.

Currie's bar has been a prominent city landmark for more than 20 years, known for hosting political leaders, dance lessons and weekly jazz nights.

Currie hopes that when the lift is fixed, he can shift back into his regular routine, a morning mobility workout, a meal at the dining room table, and a ride downstairs to greet his customers.

Tamia Fowlkes is a Public Investigator reporter. You can reach Tamia at 414-224-2193 or tfowlkes@gannett.com. Follow her on X at @tamiafowlkes.

About Public Investigator

Government corruption. Corporate wrongdoing. Consumer complaints. Medical scams. Public Investigator is a new initiative of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and its sister newsrooms across Wisconsin. Our team wants to hear your tips, chase the leads and uncover the truth. We'll investigate anywhere in Wisconsin. Send your tips to watchdog@journalsentinel.com or call 414-319-9061. You can also submit tips at jsonline.com/tips.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Milwaukee man's ordeal with wheelchair lift exposes national shortage