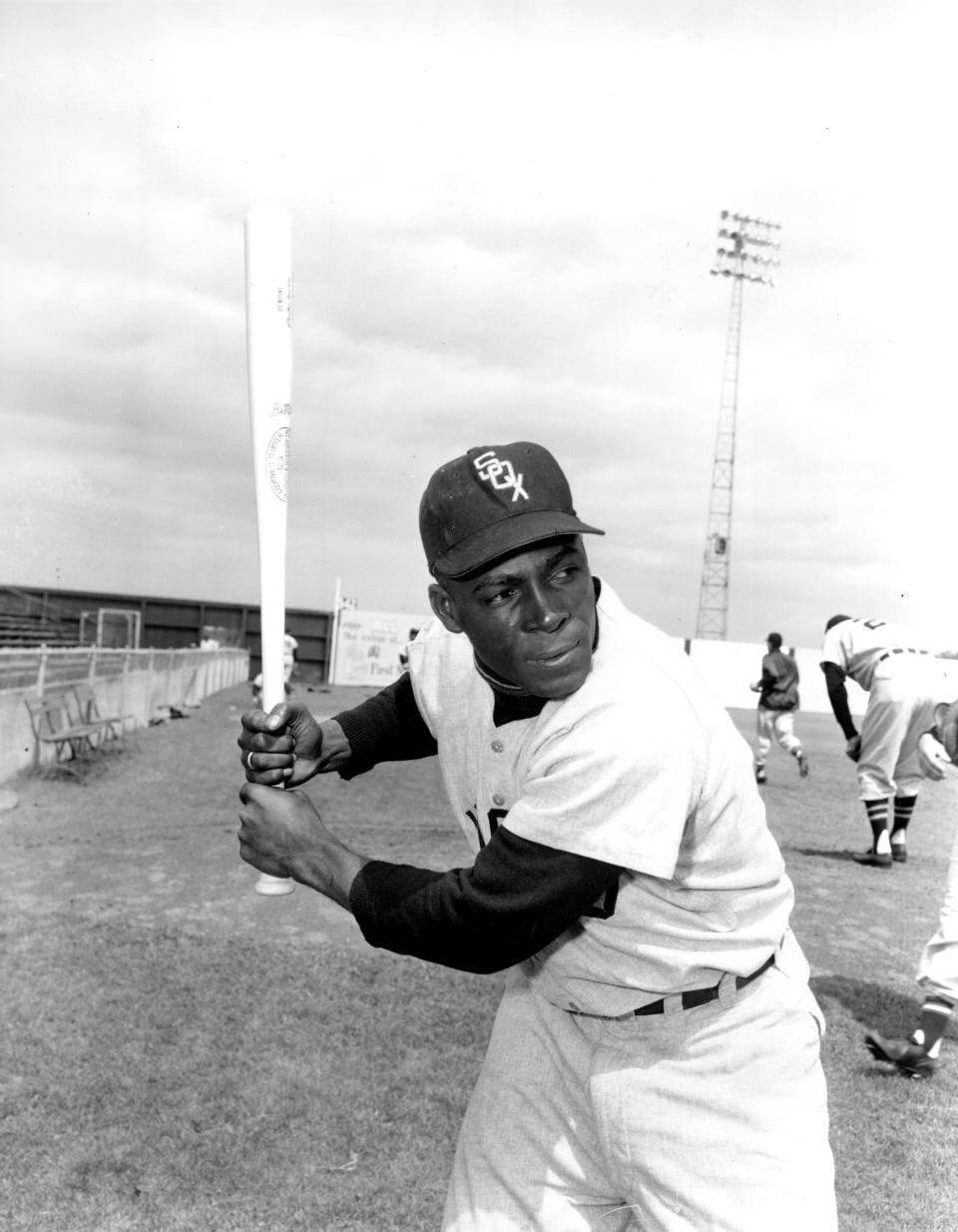

Minnie Miñoso's legacy lives on as 'Jackie Robinson' of Black Latino players

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In his native Cuba, Orestes "Minnie" Miñoso was more than just a popular baseball player, the first Latino superstar in the majors.

He was also a cultural icon, sharply dressed and driving around Havana in his signature Cadillac. His baseball exploits were even immortalized in a popular 1954 Cuban song, “Miñoso al bate” (Miñoso at bat), the lyrics proclaiming how the ball “dances the cha-cha-chá” whenever he came to the plate, whether with the Chicago White Sox or in Cuba's winter league.

Miñoso died in 2015 at age 92, but his significance in baseball sailed well beyond Cuba's shores for decades, impacting Latino players — both Black and white — in several countries.

In his 1998 autobiography, Puerto Rican-born Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda gave voice to Miñoso's impact, writing he “is to Latin ballplayers what Jackie Robinson is to Black ballplayers. As much as I loved Roberto Clemente and cherish his memory, Minnie is the one who made it possible for all us Latins. Before Roberto Clemente, before Vic Power, before Orlando Cepeda, there was Minnie Miñoso."

After three seasons with the New York Cubans of the Negro National League, Miñoso broke into the majors with Cleveland in 1949, two years after Robinson broke baseball's color barrier. Miñoso was traded to the White Sox in 1951, making nine All-Star Game appearances in that decade.

"When someone like Orlando Cepeda, who saw Josh Gibson, who saw Satchel Paige as Negro leaguers coming to Puerto Rico, when he says that Minnie was our Jackie Robinson, this is not just hyperbole," said author and University of Illinois history professor Adrian Burgos, Jr., who was the founding editor-in-chief of La Vida Baseball.

"This is about the significance that Latinos and especially Black Latinos place on the success of Miñoso to show everyone in the major leagues and MLB what Latinos who had previously labored in the Negro leagues were always capable of doing."

Miñoso was not the first Latino to play in the majors. Cuban-born Esteban "Steve" Bellán played for the Troy Haymakers of the National Association in 1871 — although the National Association is not universally viewed as a "major league." And Colombian-born Luis "Lou" Castro played for the American League's Philadelphia Athletics in 1902.

Before Robinson, only white or light-skinned Latinos could reach the majors, the most successful being Cuban-born Adolfo Luque, who played 20 seasons in the majors while compiling a 194-179 record with a 3.24 ERA. In 1923, Luque led the NL with 27 wins (eight losses) and a 1.93 ERA.

He was the first Latino to appear in a World Series in 1919, tossing five scoreless innings in two relief appearances for the Cincinnati Reds against the Chicago "Black Sox." And he was the first Latino to win a Series game, pitching 4 ⅓ innings in relief at age 43 to win the Series-clinching Game 5 in 1933 for the New York Giants against the Washington Senators.

"Adolfo Luque doesn’t mean the same thing to a Tony Oliva, to a Luis Tiant, to an Orlando Cepeda," Burgos said, "that generation of Black Latinos because the lighter-skinned Latinos got a shot. The best of the Black Latinos, they were playing in the Negro leagues and they were proving their greatness there."

In the Negro Leagues, one of Miñoso's teammates was Negro leagues legend Luis Tiant Sr., so Luis Jr. knew Miñoso long before the younger Tiant embarked on a 19-year major-league career that saw him win 229 games with a 3.30 ERA.

"He would come over with his Cadillac and they would talk over a beer," Tiant Jr. said of Miñoso's visits to the Tiant household in Marianao, Cuba. Tiant started his major-league career in 1964, the year Miñoso retired — for the first time.

"He was the one who represented all of us in the major leagues," Tiant Jr. said. "For me, he was a hero and a good friend."

Tiant even got to play against his good friend in the final season of the Cuban League in 1960-61, Tiant's lone professional season in Cuba when he was named that league's rookie of the year with a 10-8 record and 2.72 ERA.

"He was my idol," Tiant said. "Since I started playing, he was the Cuban who played the best in the majors at that time. Then he would come back to Cuba and do the same thing in winter ball. Every year he played in Cuba. ... He was a tremendous ballplayer. Compete ballplayer. Ran, hit, threw. To me, he was the best that came out of my country."

Miñoso's numbers in the majors certainly indicated that. From 1951 to 1960, "The Cuban Comet" had a WAR (wins above replacement) of 50.2, comparable to Stan Musial (54.4), Richie Ashburn (51.4) and Duke Snider (50.8) and higher than Ted Williams (46.4) during those years.

Miñoso's Latino contemporaries in the 1950s raved about him, as Cuban-born Tony Oliva, who went on to win three American League batting titles, found out after he made it to the Minnesota Twins in 1962.

"Everybody, like Camilo Pascual, Pedro Ramos, who knew him very well, Zoilo Versalles, Sandy Valdespino,would tell me about Minnie Miñoso," said Oliva, who followed Miñoso's Cuban League career on the radio as a child growing up in the countryside of Pinar del Rio, Cuba.

Like Miñoso, Hall of Famer Tony Pérez was born and raised in a Cuban sugar mill town, Miñoso in El Perico and Pérez in El Central Violeta in Camagüey. And like Oliva, Pérez followed Miñoso's career by listening to Cuban League games on the radio.

"I admired him," said Pérez, who first met Miñoso when he practiced as a reserve player on Marianao, Miñoso's club in the Cuban League for 14 winters. "I’ve always said in Cuba almost all the youth like us who were coming up in baseball, we wanted to be like him."

It wasn't just fellow Cuban players who admired Miñoso. Burgos points to the bond that developed between Miñoso and Venezuelan-born Hall of Famer and White Sox teammate Luis Aparicio. And Jim Rivera, a New York-born Puerto Rican player, talked about Miñoso being a role model.

"These guys actually saw how the other players treated Minnie when they were not welcoming Black players to baseball," Burgos said. "So, they have this kind of insight about what it means to be a Black ballplayer and how Minnie carried himself."

And Miñoso continued to be a role model into the 21st century, maintaining his ties to the White Sox as the pipeline of Cuban talent continued to flow into Chicago's South Side with the recent additions of Cuban players, such as Alexei Ramírez, José Abreu, Yoán Moncada and Luis Robert.

When Miñoso died on March 1, 2015, Abreu, the 2014 AL rookie of the year and 2020 AL MVP, talked about Miñoso as a mentor.

"When I came to the U.S. and had the opportunity to meet him it was a special moment because all the background that my father told me about him," Abreu said at the time. "He was a great person, he was outstanding with me and it's an honor when you're able to be around a person as good as him."

Burgos said all the Cuban players on the White Sox in recent years appreciated Miñoso's place in history.

"They knew this is a giant," Burgos said. "The best parallel I can draw to that is Dominicanos with Felipe Alou. There’s a reverence. 'We are in the midst of our baseball royalty.'"

In a 20-year major-league playing career that spanned five decades — he briefly came out of retirement in 1976 (8 at-bats) and 1980 (2 at-bats) — Miñoso batted .299 with 2,110 hits, 195 home runs, 1,093 RBI and 216 stolen bases and had 13 All-Star Game appearances.

In 15 years on the Baseball Writers' Association of America ballot, Miñoso never got higher than the 21.1% of the votes he received in 1988 and was dropped from the ballot after getting just 14.7% of the votes in 1999.

He also has been passed up in veteran committee votes, most recently in 2014, when he received only eight votes (50%) from the 16-person Golden Era Committee, four votes shy of induction. Oliva missed by one vote.

"That’s a lack of respect," said Tiant, who got "three or fewer" votes. "With everything that man did in baseball, not just for Blacks, not just for Latinos, for whites, everybody. ... That was a lack of respect."

Oliva and Pérez also believe Miñoso should be in the Hall of Fame.

"Yes, he should be," Pérez said. "He was one of the ones who opened the path for Latino and Black players. He’s part of that group and that should be taken into consideration."

At one point, Miñoso was among dozens of Negro league players and executives whose Hall of Fame credentials were being considered by a committee of 12 Black baseball scholars and historians, including Burgos, who was tasked with making the case for Miñoso. Despite Burgos' lobbying, Miñoso was not among the 17 elected to Cooperstown in 2006.

The committee concluded that the special election was not the proper venue to determine Miñoso's credentials because he only played three seasons in the Negro leagues.

"I understood the vote," said Burgos, who believes Miñoso merits induction not just because of his play on the field — that his role as a pioneer should be taken into consideration as well.

"I hope that with MLB now recognizing that Negro league (baseball) was what we always knew it was — it was major league — that people would take a second glance at what Minnie had accomplished, and not just think about the statistics. Think about the entirety of that historical era, of what men like Miñoso, Robinson, Larry Doby, Monte Irving and Oliva and Tiant all went through to achieve their success in major league baseball and yes, the social factors should matter because it was what they had to combat to be on the field, to succeed on the field."

Cesar Brioso is author of "Havana Hardball" and "Last Seasons in Havana."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Minnie Miñoso, MLB's first Black Latino star, was a baseball pioneer