This Is a Minute-by-Minute Breakdown of the Ever Given’s Crash

Late last month, a colossal container ship called the Ever Given ran aground in the Suez Canal, ensnaring one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes in a marine traffic jam for 6 agonizing (and expensive) days. Salvage crews finally wrenched the Ever Given free from its perch—with a key assist from the moon—on March 29, but the ship remains anchored in Egypt’s Great Bitter Lake for inspection as of press time, with further investigations pending. Here, using publicly available ship tracking data and insight from maritime pilots, Popular Mechanics pieces together precisely how the disaster dramatically unfolded in real time.

Drifting Slowly in a Patternless Pause

On Tuesday, March 23, at 12:12 a.m. Egyptian local time (EET), the Ever Given, a container ship belonging to the shipping company Evergreen Marine and sailing under the flag of Panama, arrived at Suez Port. Nobody cared.

In the darkness, the 1,300-foot long, 200,000-metric ton megaship joined a group of vessels already idling in the anchorage—an enormous, yet unremarkable addition to a vast, aquatic waiting room at the foot of the Suez Canal’s southern terminus. For the next 5 hours and 37 minutes, the Ever Given drifted slowly in a patternless pause, killing time before the start of its half-day-plus voyage through the canal to the Mediterranean Sea.

⚓️ You love badass ships. So do we. Let’s nerd out over them together.

At 5:49 a.m., the Mosaheb 2, an Egyptian tugboat, sidled up to the skyscraper-sized ship, the official indication that the vessel’s journey was about to begin.

One hour and 53 minutes later, the Ever Given’s voyage was over. By then, it was the most famous ship in the world.

‘Thrilling Winds of Sand and Dust’

Days earlier, the Egyptian Meteorological Authority (EMA) had started to issue warnings. Infamous seasonal gusts of hot, dry, and sand-filled air, known as the Khamaseen winds, were sweeping intensely across the country, causing dramatic spikes in temperature and poor visibility. In a forecast for March 23, the EMA warned of “thrilling winds of sand and dust” and a “disruption of maritime navigation.” Wave heights on the Gulf of Suez and the Red Sea, the EMA estimated, would reach 10 to 13 feet.

This information was likely top of mind for the Suez Canal Authority (SCA) pilots aboard the Mosaheb 2 as it approached the Ever Given on Tuesday morning. Pilots, who are required aboard all vessels transiting the canal, use their local expertise to verbally direct the navigation of a ship as its captain maneuvers it through the man-made passage.

On a normal day, pilots are a formality, a helpful addition to the ship’s bridge; when chaos strikes, they can be the last line of defense between a close call and an incalculable disaster.

At 5:53 a.m., the Mosaheb 2 departed the Ever Given, leaving behind two SCA pilots that would stay in the ship’s bridge until it reached Ismailia, a city near the canal’s halfway point. There, they would exit the ship and be replaced by new pilots, who would ride with the vessel until its passage through the canal was complete.

Captain John DeCruz is an expert in what can unfold on the bridge of a ship like the Ever Given from this point forward. DeCruz is the New York President of the Sandy Hook Pilots, one of a handful of organizations responsible for guiding vessels into and out of New York Harbor. For nearly two decades, DeCruz was an active pilot himself, guiding ships of all sizes through the waters of New York and New Jersey. Before he was a pilot, DeCruz worked on a ship that brought him to the Suez Canal.

According to DeCruz, the arrival of the two SCA pilots at the bridge of the Ever Given would initiate a briefing with the captain.

“You find out everything you need to know about the ship,” DeCruz tells Pop Mech. “If there’s any issues that they encountered on the way, you tell them if they’re going to encounter any traffic coming in, how many ships we’re going to meet. You give the captain of the ship a rundown of everything that we expect to see on that transit.”

The Suez Springs to Life

At 6:00 a.m., just 7 minutes after the pilots’ arrival, Suez Port sprung to life, with a select convoy of the day’s largest, top-priority vessels now officially cleared to sail northbound and enter the canal. First in line was the Al Nasriyah of the Marshall Islands, followed in order by the Cosco Galaxy of Hong Kong, the Ever Given, the Maersk Denver of the U.S., and so on. At 6:21 a.m., the Al Nasriyah turned to the north and started its transit to the canal’s entrance. The convoy had begun.

At 6:51 a.m., the Al Nasriyah arrived at the southern terminus of the Suez Canal. Seven minutes later, while navigating the canal’s approximately 4.3-mile gradual opening turn, it was joined at its stern by the Mosaed 2, a local tugboat employed to help direct its passage. Shortly thereafter, the Cosco Galaxy also picked up a tugboat, the Mosaed 3, which positioned itself behind the ship.

At 7:18 a.m., the Ever Given entered the Suez Canal, choosing, curiously, to proceed without a tugboat. Unlike pilots, tugboats aren’t a mandatory feature of a ship’s transit through the canal—the Maersk Denver, trailing the Ever Given, also proceeded without one. However, their usefulness as an extra precautionary measure, particularly during bouts of bad weather, is undeniable.

“If something goes wrong, you have something to help you,” Captain Robert Flannery, an active pilot and the President of New York’s Metro Pilots Association, tells Pop Mech. “They help you maneuver, they help you slow down, they can help guide your bow and your stern, and God forbid you lose an engine or something happens, you got a fighting chance. If you don’t have a tugboat, you’re shit out of luck.”

‘Too Much Speed for These Ships in a Tight Area’

At 7:22 a.m., as it took the opening turn of the canal, the Ever Given was alone. Up ahead, the Al Nasriyah was near the canal’s 151-kilometer (km) marker—its distance from the northern terminus at Port Said—with the Cosco Galaxy keeping pace. Behind the Ever Given, the Maersk Denver edged toward the canal’s entrance.

At this moment, the Ever Given’s speed, which had been gradually increasing and had already eclipsed the 8.6-knot limit set by the SCA, began to approach eyebrow-raising levels. By 7:29 a.m., as it pulled out of the opening turn, the Ever Given was traveling at 13.7 knots.

When DeCruz watched the Automatic Identification System (AIS) video replay of the Ever Given’s entrance to the canal, the number 13 jumped off his screen. Simulated voyages and live experience navigating slightly smaller megaships had made clear to him the dangers associated with such speeds.

“We determined that was too much speed for these ships in a tight area,” said DeCruz.

The pilots aboard the Ever Given, however, may have had no choice but to recommend an acceleration to the captain.

According to a statement issued by the Suez Canal Authority, as forecasted, powerful dusty winds bore down on the canal on Tuesday morning, lowering visibility and gusting at speeds as high as 46 miles per hour (mph). If a crosswind of that magnitude struck the Ever Given, the 18,300 shipping containers stacked high above it would have collectively acted as an enormous sail, and caused the ship to drift in the direction of the wind.

To effectively counter such a gust, a pilot would likely prescribe increased speed and an angled course against the wind.

“You can’t steer straight if it’s blowing you sideways,” Flannery says. “You’ll be aground. Speed gets you through it quicker.”

The Bank Effect

At 7:37 a.m., the Ever Given, traveling at 13 knots, appeared to initiate an approximately 2-minute northwesterly push toward the west bank of the canal, a maneuver presumably made in response to winds that had gradually pushed the vessel towards the east bank.

At 7:39 a.m., the Ever Given straightened and was again parallel with the canal, but was now sailing close to the edge of the west bank.

Ships like the Ever Given don’t mix well with banks. When a vessel of its size sails alongside one, the strip of water between the land and the ship is squeezed and displaced. As a result, the water’s flow quickens, its pressure drops, and, as it shallows in the ship’s wake, it sucks downward, like a flushing toilet, pulling in the stern of the vessel. This phenomenon, known as the bank effect, can wreak havoc on megaships, which displace large quantities of water and cannot correct course quickly if knocked off kilter.

At 7:40 a.m., the stern of the Ever Given suddenly swung toward the west bank of the Suez Canal, evidence that the ship had started to bank. As the stern swung clockwise to the west, the bow, pushed by the ballooning cushion of water between it and the west bank, swung clockwise to the east. The Ever Given was out of control.

“At that point, due to the displacement of that type of ship in that canal, the water was just taking it wherever the water wanted to go,” DeCruz says.

On the bridge of the Ever Given, the two SCA pilots and the captain now faced an emergency. Action was paramount.

“There’s no time for conversation,” Flannery says. “You need to concentrate on what you’re doing. We act now, talk later.”

“There were two pilots up there,” says DeCruz. “I guarantee you they were trying everything they could to see what was going on.”

The Grounding of the Ever Given

At 7:41 a.m., with the Ever Given’s bow careening toward the east bank, the only logical navigational option was to turn the ship westward. But, according to DeCruz, at that stage, the suctioned stretch of water between the west bank and the ship’s stern was likely too shallow for the vessel to gain the traction needed to change course.

“Once that stern tucked in, there was no way of turning the ship left,” says DeCruz. “There was nothing there but a limited amount of water. The propeller couldn’t do anything and the rudder couldn’t do anything.”

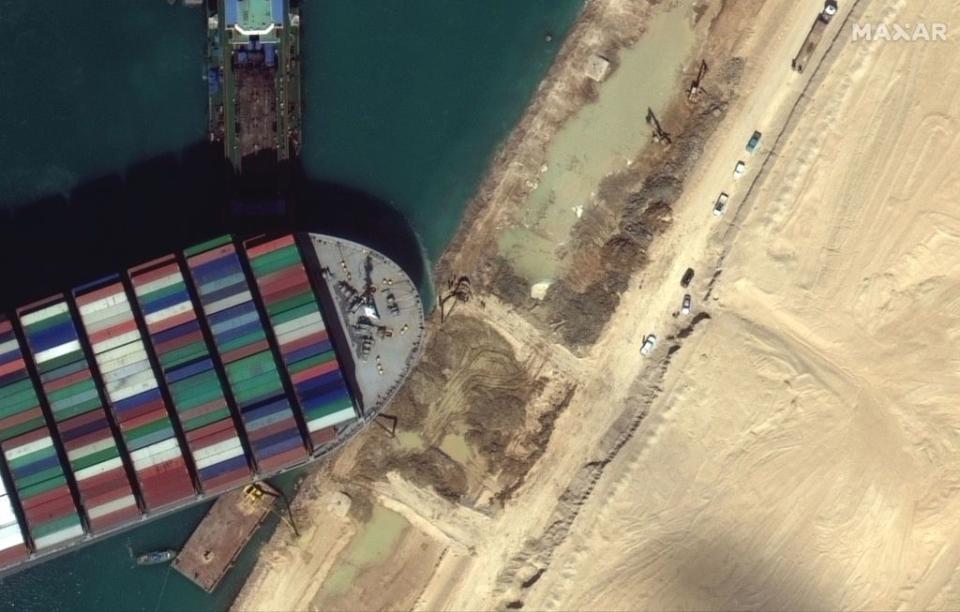

At 7:42 a.m., the Ever Given ran aground, driving its bulbous bow into the east bank of the canal at the 151-km marker. A minute later, its stern, drifting clockwise, connected with the west bank. The Suez Canal was officially blocked.

When a ship runs aground, crisis management begins instantly on the bridge. According to DeCruz, tugboats must be called and engineers must be dispatched to ensure that the boat is not taking on water or leaking fuel.

“You ain’t going nowhere,” said Flannery. “It’s time to make phone calls.”

One of the Ever Given’s phone calls likely reached the northbound Mosaed 2—the aforementioned tugboat trailing the Al Nasriyah—which, at 7:57am, turned on a dime near the canal’s 146-km marker, and sped south toward the Ever Given.

By 8:17 a.m., the Mosaed 2, along with the Mosaed 3, had reached the grounded ship. Thirty-five minutes after it struck land, the Ever Given’s rescue operation was underway.

Seven days, six hours, and 48 minutes later, that operation ended. On March 29 at 3:05 p.m., the Ever Given was refloated and, by 3:58 p.m., it had eased back into the canal, en route to nearby Great Bitter Lake for inspection.

As of press time, the Ever Given is still sitting in the Great Bitter Lake. Investigations, undoubtedly, are forthcoming, and blame will surely be passed around to all concerned parties. Eventually, the Ever Given will depart the lake, sail to and through its northern terminus at Port Said, enter the vast Mediterranean Sea, and press onward to its next destination. Out of sight, out of mind, but anonymous no more.

🎥 Now Watch This:

You Might Also Like