Misconduct accusations against this Arizona doctor span a generation. But he kept his medical license

Editor’s note: This story contains descriptions of sexual abuse that may be disturbing. The Arizona Republic generally does not name victims of sexual assault.

Panic faded to embarrassment as Meredith Younce drove away from her doctor’s office. She tried to rationalize:

Did that just happen? OK, it did happen. But why?

She decided it was wrong. The 22-year-old craved validation, she told The Arizona Republic.

She called another person she should trust. Again, she was let down.

Her boyfriend dismissed her that day in 1998, she said. Contacted by The Republic, he confirmed her account.

“Oh, Meredith,” she recalled her boyfriend saying, “he’s a doctor, he sees lady parts all the time.”

“No,” she said. “He’s a pediatrician, not a gynecologist.”

When she got home, her boyfriend was waiting with news: she needed to talk to the police, there were other women.

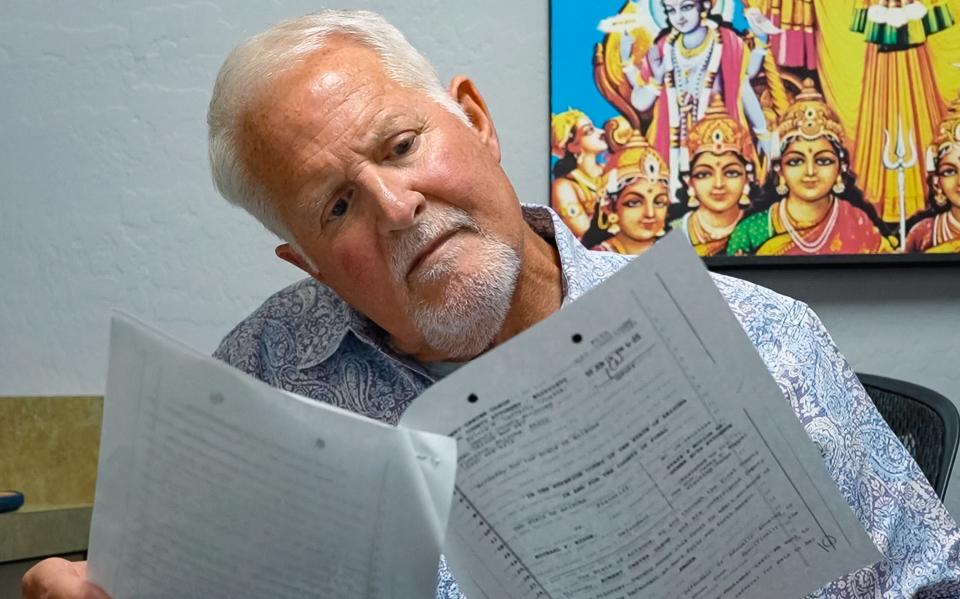

At his Casa Grande office, Dr. Michael Ridge spoke with The Republic in September. He denied Younce’s claim. He also denied, one after another, sexual misconduct claims made about him by 13 other women in court and medical board documents.

Ridge welcomed the interview. He beat criminal sexual misconduct charges 24 years ago and settled a related lawsuit. He held a lingering concern about what the Arizona Medical Board could do, though he has emerged from its scrutiny at least 11 times for a variety of issues and kept his license.

Ridge, 71, continued to practice medicine despite complaints to the state medical board, including issues with record-keeping, complaints about bad drug prescribing and four sexual misconduct complaints across a generation of women.

In the court of public opinion, and in criminal court, Ridge got the benefit of the doubt. Claims that Ridge abused his patients were judged by a changing cast of medical board members, but their reactions were similar. In those cases of he said vs she said, the board didn’t side with the women, despite similar claims spanning decades and the #MeToo global reckoning about the handling of sexual misconduct.

The board considered complaints that Ridge sexually abused two patients in 1998.

In 2003, it investigated an allegation that Ridge inappropriately touched a patient.

In 2011, it looked into a complaint from a woman who said Ridge inappropriately exposed her breasts and stomach during an appointment.

And again in 2021, it looked into a complaint that Ridge unnecessarily exposed a woman’s breasts during an abdominal exam.

Three times between 1999 and 2022, the board ordered Ridge to have a “chaperone.” It’s an unusual requirement that another trained professional monitor his exams of women. He was written up for violating that order.

Ridge is joined by six other doctors in Arizona who the board requires to have chaperones.

That includes one doctor left in place after committing a crime: The board gave a second, then a third chance to a registered sex offender. He holds his Arizona medical license to this day.

Why the board didn’t take further action is difficult to pin down. Their investigations aren’t public. The board is mandated by law to protect patients, but it’s mostly composed of fellow doctors. The board has fought to keep its records so secret they can’t even be revealed in civil court, much less to patients.

Questions to current board members largely went unanswered. The board’s executive director, Pat McSorley, declined an in-person interview and asked that questions be submitted by email. She said that would be more accurate, but she did not respond to some of the questions asked.

The board is busy, according to McSorley. Seven investigators handled 1,160 complaints in the past year — about 165 per investigator. She said their investigations are uncompromised by the workload, but they’re asking the state for more money for more staff.

Another 812 complaints were simply discarded because state laws tie the board’s hands in some cases: They can’t take anonymous complaints or investigate misbehavior more than four years old, among other restrictions.

It doesn’t get much better in other states. Despite its flaws, Arizona’s board ranks highly among other states for taking action against doctors.

The board is mandated by law to coordinate with law enforcement to investigate possible crimes. But at least three times the board got complaints of Ridge inappropriately touching or exposing his patients and did not pass them on to local police.

Eleven women spoke out against Ridge as revealed in 1999 criminal court proceedings. His public file shows the state medical board investigated two complaints at the time.

In the following years, Ridge was accused before the medical board of victimizing another woman.

And another.

And another.

That whole time, the board left Ridge free to see patients.

"It happens way too often and when it comes down to the woman's word against a doctor's word, the medical boards are going to take the doctor's word most times,” said Lisa McGiffert of the Patient Safety Action Network, a national patient advocacy group.

In all, 14 women formally accused Ridge. He reasoned the stories they told about him couldn't be real.

“I don’t know how you could possibly do any of that kind of stuff,” he said, “and get away with it.”

A visit to the doctor, then a visit to police

The Republic exposed allegations against Ridge and the board’s handling of him by filling in gaps in his state licensing file with police and court documents that contain additional claims of sexual misconduct.

Suspicions about Ridge first became public in his 1990s criminal trial. It started with five women, including Younce.

As a doctor in a rural area, specializing in internal medicine and pediatrics, Ridge was widely respected and widely defended.

In an interview, Ridge wore paisley, called himself a “hippie” and said patients love his joking bedside manner. He landed in medicine in part because his deep musical appreciation couldn’t compensate for a lack of musical talent. His office is adorned with Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix posters. He boasts he helped birth a Jonas brother. No kidding ― Joe Jonas donated to the hospital, which has a nursery bearing his name.

Back in 1998, Casa Grande, a suburb of Phoenix, was half its current size.

Younce said she was a patient of Ridge’s partner, Dr. Douglas Parkin.

In February 1998, Younce had a jampacked schedule of work and class, and she had a bladder infection. She had dealt with those before. Treatment was usually pretty quick. No physical examination, just a prescription for antibiotics.

But this time she couldn’t get an appointment with Parkin, so she scheduled an appointment, for her lunch break, with Ridge.

She described her encounter with him in an interview with The Republic.

It was chilly. Her 5-foot, 95-pound frame was cocooned in an oversize knit sweater. She wore trendy stirrup pants ― essentially leggings with loops around her heels. And an elastic waistband.

She sat in a small exam room and she waited.

Ridge arrived, with a quip:

“So you’re peeing fire, huh?” she remembered him asking.

He seems a little goofy, she thought.

He directed her to lie back on the exam table, asking questions about symptoms.

He pulled her sweater up and her waistband down, she said.

Younce thought: Which underwear am I wearing?

You don’t want a doctor to see your crummy underwear.

Why is he looking at my underwear?

Then he exposed her entire pubic area.

The moment he did, she threw her hands over her blushing face. It was a childlike defense: If I can’t see you, you can’t see me.

Suddenly, he stopped. He pulled her underwear and pants back up. He talked about an antibiotic, but Younce recalled he didn’t explain what he did.

“I couldn't hear what he was saying,” Younce said. “I was just thinking in my head ... it's a bladder infection ― what is he looking at?”

Looking at a patient’s genitals in the way Younce recalled does not have a medical purpose, according to Dr. Burton Bentley, who runs a firm of medical experts in Tucson and said he has testified in court many times himself.

At the front desk, Younce longed for consolation. Instead, she got a bill.

You’re going to pay $80 for some quack who just took a free peek at your lady parts, she thought.

Ridge denied Younce's account of the exam.

“It didn’t happen,” Ridge told The Republic. “But to say that I remember it now, I’d be lying to you. And I’m not going to lie to you.”

Younce’s boyfriend had a strong mom. Kay Kerby’s obituary in September boasted that she didn't suffer fools.

Kay heard her daughter’s friend had a similar run-in with Ridge. So when her son told her about Younce, she took action.

She brought Younce to Casa Grande police Detective Michael Glaser.

A police records clerk found the detective’s 25-year-old report but not the recordings of interviews the report says he made. His report on Younce shows the next day he talked about Ridge to two other women, whom The Republic is identifying by initials.

R.M. told the detective in February 1998 she had been a patient of Ridge’s for more than 10 years and she complained about him to the state medical board. A person identified publicly by the board by the same initials made a complaint to the board dated January 1998.

She hurt her knee and went to Ridge’s office for a referral to an orthopedic specialist. She wore a dress. Ridge had her lie on the exam table.

She said that Ridge moved her legs apart "and literally stuck his head between her legs for a better view,” the detective reported.

Ridge pulled her dress up and her underwear down. He pressed around her pelvic area, asking if it hurt.

"No,” she said. “I told you, I hurt my knee only.”

Ridge then had her stand on the floor while he went behind her. He pulled up her dress and ran his hand all the way down from the bottom of her buttocks to below her knee.

"Did that hurt?”

"No, and that is the wrong leg.”

Detective Glaser largely declined to comment when reached by a reporter.

“I believed the women then,” Glaser said, “and I have no reason not to believe them now.”

The detective’s report shows he also talked to B.R., also in February 1998.

She told him she felt uncomfortable seeing Ridge for the past year. She went to Ridge for abdominal pain. Four to six times, he pulled her pants down or asked her to.

“She thought that this was strange but he was the doctor and believed that he must know what he was doing,” the detective wrote.

The last time she saw Ridge was about moles on her back, a month prior.

He asked her to get on the exam table. She showed him the moles. He asked if she had looked for others. She said she had checked herself, and she didn’t have any.

He told her to unbutton her pants, and pulled them down, saying he wanted to check for more.

He checked her legs.

She felt his whole hand underneath her vagina. He pushed on it twice and asked if she ever had pain there. She said no. He spread her vulva and looked at it.

She was sure it was just a short moment. It seemed like a long time.

The detective gave her a box of Kleenex as she cried.

In an interview with The Republic, Ridge denied what the women said about him.

The detective got a search warrant for Ridge’s office and showed up after hours, when Ridge wasn’t there.

The detective told Ridge’s partner, Parkin, that several women had made claims against Ridge. Parkin said he didn’t know of any complaints from women. An obituary shows Parkin died last December.

Parkin said there wasn’t a written policy on treating women, but he always had a nurse present just to “cover himself,” the detective’s report shows.

Parkin asked: “He didn't penetrate any of these women, did he?”

The detective later spoke to Ridge in a police station interview room.

R.M.’s account didn’t ring any bells, Ridge told the detective. He may have pulled her pants down to feel her “groin pulses.”

Groin pulses?

The detective asked: Was that a normal thing?

“Yeah,” Ridge said.

The detective asked Ridge about B.R.

"I gave her whole body kind of a look because she worries about moles,” Ridge said. "I didn't take her clothes off or anything like that, I may have pulled her pants down to look at the mole I had removed previously.”

The detective asked: Is there any reason Ridge would check her vaginal area?

There was not, Ridge told him.

"I believe that I must have done something that offended them, but it wasn't a conscious thing,” Ridge said.

The detective arrested Ridge on two charges of sexual abuse, searched him and booked him into Pinal County Jail.

“It happened so fast,” Younce said. She was shocked, but glad. She thought: he won’t be practicing medicine now.

But just as quickly, the town responded.

Ridge’s name and charges hit the local paper. Just the basics in 341 words. The women weren’t named, their stories weren’t told.

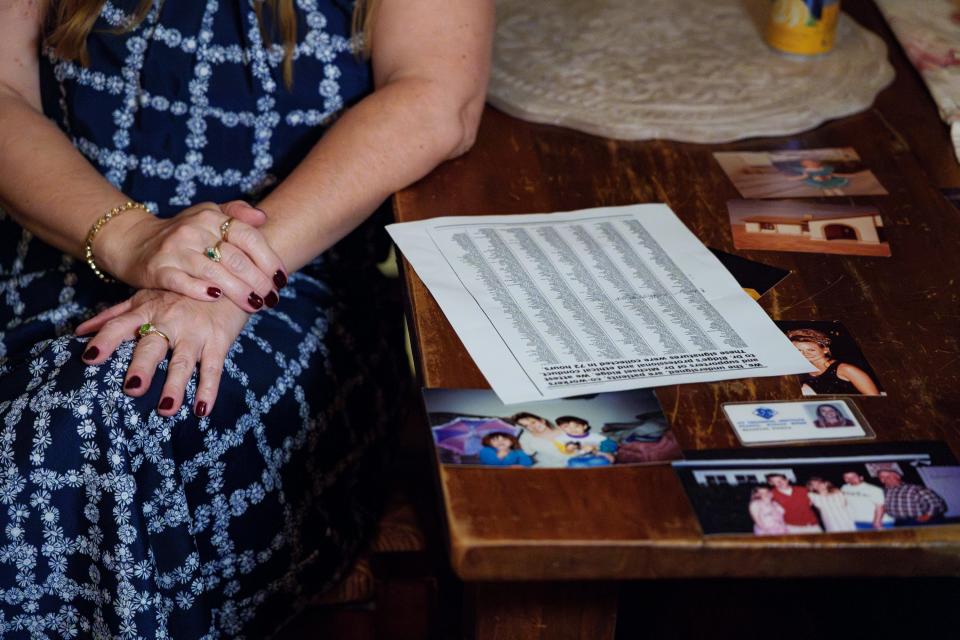

Even so, more than 500 people promptly signed a full-page newspaper ad categorically endorsing Ridge, attesting to his “professional and ethical conduct” and boasting they came together in 72 hours.

Younce was shocked.

“My school principal signed it,” she said. “My French teacher signed it. My government teacher signed it, other girls on the cheerleading squad. My dad’s mechanic.”

Ridge said the ad made him feel good. In an interview, he said he figured the folks in town liked his humor and cracked a joke about God coming to Earth as a doctor.

As news of Ridge’s arrest spread, the detective got an anonymous phone call. The caller told him that one of Ridge’s former office managers saw it coming.

The detective later tracked down the office manager, Jean Pasell. She couldn’t remember the complaint exactly, the detective’s report shows. She recalled in about 1986, a woman raised concern about getting a breast or pelvic exam when the patient hadn’t come in for one.

When Pasell talked to Ridge, he just “laughed it off,” the detective’s report shows.

Pasell told The Republic that before the criminal charges against Ridge, she met with two women on different occasions who were distraught and angry. She said they felt Ridge touched them inappropriately.

The detective also learned about a ruling the state medical board issued to Ridge.

In the months after Ridge’s arrest, on May 21, 1998, as a result of complaints from two people identified publicly by the board only by the initials B.R. and M.Y.B., the board ordered Ridge to “have a female chaperone present during all examinations of female patients, in all work settings.”

Less than six weeks after the board’s order, the detective heard Ridge wasn’t abiding. The detective spoke casually with a Casa Grande police dispatcher. Ridge saw her for a “female examination,” and she told the detective Ridge saw her alone, though she said nothing unusual happened during the exam.

The detective drafted a one-page report, but the concern never made it into Ridge’s file with the state medical board.

Jury hears allegations from 6 women

As the case moved toward trial, Pinal County prosecutors found more women who accused Ridge of sexual misconduct.

Two more women were added to the criminal complaint, for a total of five.

The Republic tried to contact every identifiable woman who formally accused Ridge. Only Younce was willing to speak publicly. Some said they were afraid of retaliation.

One woman saw Ridge for allergies in May 1997 and he “yanked on her belt and unzipped her shorts; he then stuck his hand inside her shorts and pressed on her crotch around the area of her pubic hair,” the state claimed in a court filing 16 months after Ridge’s arrest.

The other woman saw Ridge twice for a sore throat in November 1997, the state claimed. Both times, he pulled up her bra and squeezed her breasts.

As court events unfolded, prosecutors said in a filing they found six more women who they said made similar formal claims that Ridge inappropriately touched them, dating from 1987 to 1998. They included a woman hospitalized with a kidney problem who said she woke in bed to find Ridge opening her labia. Patients said Ridge lifted their shirts when they saw him for colds and a woman said he fondled her vagina during an exam.

“It was just weird,” that last woman said.

The Republic asked Ridge to respond to each of the allegations of misconduct described in public documents. He denied almost every claim.

He conceded a single point: One woman claimed she saw Ridge in September 1997 for a pelvic exam and he did a breast exam, too. Ridge said that was normal.

The stack of allegations against Ridge exists in an official court document filed by state prosecutors. But Ridge’s court file shows prosecutors weren’t allowed to tell the jury about many of those claims.

Maricopa County Superior Court Judge James Keppel allowed into evidence one woman’s story of Ridge “touching of her vaginal area in a sexual way,” and ruled that act provided a basis to infer Ridge had “an aberrant sexual propensity” to commit the crimes he was charged with.

Keppel could not be reached for comment.

The judge found there was sufficient evidence to conclude Ridge committed the acts described by four other women. And he ruled they could demonstrate Ridge behaved unprofessionally. But the judge’s job at that moment was to determine whether the acts were relevant to the criminal trial, and he decided they weren’t.

So state prosecutors were allowed to tell the jury about their five main victims and the additional woman the judge allowed.

The defense took shots at the women in court filings. At least two of their witnesses saw a connection between promiscuity and a lack of credibility.

The judge denied most of the defense’s efforts to bring in victims' sexual history.

The defense wanted to tell the jury more about one accuser. She had sex with Ridge’s stepson the same day she said she was abused by Ridge.

The judge wrote: “The court finds that the fact of her sexual encounter shortly after the alleged conduct of the defendant would be relevant to (her) credibility.”

He allowed it.

Ridge’s attorney was nervous, the Casa Grande Dispatch reported at the time. He thought the evidence was weak, but there were just so many women.

“The normal, natural disposition when there are so many victims" is to assume their allegations are rooted in truth, the newspaper quoted him saying.

The jury of four men and four women pondered the case through dinner, returning in 5½ hours.

The verdict came down: not guilty.

“Especially in a small town, people hold their professionals, doctors and lawyers, they somewhat put them on a pedestal,” said Jeff Sandler, one of the prosecutors who tried Ridge.

“You don’t want to think that somebody you trusted your life to … would do something like sexually assault another patient.”

Another prosecutor gave Younce a hug.

“They said there wasn’t enough evidence,” Younce recalled the prosecutor saying of the jury.

There aren’t pictures, there’s no hidden video. It’s just their word.

“What evidence would there be,” Younce mused, “other than us telling you what happened?”

Younce went on with her life, but Ridge lingered on her mind.

“Either he would get in trouble again or something, something will happen,” she said.

She was right.

But for now, for Ridge, it was time to celebrate.

A few weeks after he was acquitted, his wife threw a party at a restaurant in town. Ridge figured 300 to 400 people came, including a few local police officers. Like much of the crowd, they were his patients.

Ridge said he danced with his nurse.

“I think it's easier when you don't feel guilty,” Ridge said. “I had faith in the system. And my wife had faith in me.”

He dismissed the women’s accusations as a setup to a “shakedown” ― after the criminal trial, he settled a lawsuit brought by two of them. Court records don’t give a settlement amount, but he recalled it was about $30,000 each. Younce wasn’t involved; she said she didn’t want Ridge’s money.

He said the town saw them as “trashy” and said one spent her settlement on “breast implants.”

Ridge filed a lawsuit of his own, targeting Casa Grande and the detective who investigated him. He made claims including negligence and malicious prosecution. Available court documents don’t show the outcome, Ridge couldn’t remember filing it, the detective declined to comment and the town had no record of a settlement.

During his criminal trial, Ridge had described the pace of his thriving practice as “full-tilt boogie.”

With the legal drama behind him, he went back to work.

Complaints about Ridge add up at Arizona Medical Board

It was unclear whether all the allegations brought up in the criminal case made it to the Arizona Medical Board. Though the judge in Ridge’s criminal case ruled the accounts of four women could demonstrate Ridge behaved unprofessionally, they are not in his publicly accessible file from the state. The board’s investigative file, which could show more complaints by patients, is confidential pursuant to statute.

The board “was aware of the 1998 criminal case and an investigation was opened,” McSorley, the board’s executive director, wrote in an email. The board ordered Ridge to use a chaperone based on the two complaints to the board.

McSorley wouldn’t say whether the board considered the claims of all 11 women who came forward against Ridge as part of that trial, citing the confidentiality of its investigations.

The file does show in April 2003, about five years after he was ordered to have a chaperone, the board checked 10 of Ridge’s patient charts and found he didn’t get a chaperone’s signoff on four. He told The Republic he did have a chaperone, but she messed up the paperwork.

Ultimately, the board largely saw it his way.

As part of the same action against Ridge, the board considered another accusation about his behavior. M.A. was the 12th woman to come forward, in June 2003.

She went to Ridge to manage her pain medication.

She told the state medical board while she was alone in an exam room with Ridge, he “inappropriately engaged in physical conduct of a sexual nature by running his hand up the inside of her leg, over her panties in her crotch area and back down her same leg and thigh.”

Ridge told The Republic it didn’t happen. He recalled that she dressed in cowboy boots, “but inappropriate looking.” The board’s findings of fact, with no explanation of the significance, also noted her footwear.

Her husband and co-workers told her to cancel another appointment with Ridge. But she decided not to cancel.

“She wanted to see Dr. Ridge, in part, to be able to confirm to at least herself, the assault had occurred,” the board wrote.

But she didn’t confront him. Ridge adjusted her medication, and the visit was uneventful.

She was a nurse at a nearby hospital. About a week later, Ridge heard she told other hospital staff about the first encounter. He confronted her.

“She was in the break room, telling all this bullshit,” he told The Republic. “So I went in there, and went at her: ‘You need to shut up. This isn’t true, you’re being totally inappropriate.’”

The Arizona Medical Board is supposed to forward allegations of crimes to law enforcement. McSorley declined to comment on the case, citing the confidentiality of the board's investigations.

A Casa Grande police spokesperson said the department had no record of receiving M.A.’s complaint from the board.

A doctor, a lawyer and a former police chief each said the board should have forwarded the complaint to police.

"I believe it's negligent for the board not to do that,” said Stanley Kephart, former chief of the Salt River Police Department, who now works as an expert court witness. "You have failed in your duties and that placed people at risk."

The board held an emergency meeting months later, in October 2003, to address the issues with Ridge. They discussed Ridge’s “prior history of this type of allegation,” their minutes show.

His attorney said he “religiously followed the order” to have a chaperone, the board’s minutes show.

Ridge noted his acquittal and told the board “this situation has changed his life and he takes every precaution to protect himself from any accusations.”

The board was worried, its minutes show.

“At one time he was considered a risk to female patients because he is under a current order not to examine female patients except in the presence of a female chaperone,” the minutes show. “Since the time of the stipulation agreement in 1998 there has appeared to be lack of compliance.”

For a second time, the board ordered Ridge to have a female chaperone present “any time he is in the office.”

But the board also included the comments of a nurse who said when the woman went back to Ridge for a second appointment, she wore “tight jeans and a low cut blouse.”

Again, the board’s findings give no explanation for including the details about her outfit.

An administrative law judge later found the 12th woman's account wasn’t credible.

“It makes no sense that M.A. went back to Dr. Ridge for a second visit shortly after he allegedly committed a horrific sexual assault to her,” the board quoted the judge as saying in an April 2004 order.

Even so, the judge recommended Ridge’s license be restricted and that he have a female chaperone “in all work settings where he is with a female patient.”

The board gave Ridge a letter of reprimand for failing to have a chaperone, but in the same order they also did away with the requirement that he have one.

Seven years later, in 2011, the medical board got another complaint. And again, it sided with Ridge.

A woman said Ridge “inappropriately exposed her breasts and stomach during an appointment.” Between court filings and complaints to the board, this brought the total number of women who had made similar complaints about the doctor to 13.

The board found there was “insufficient evidence” to sustain allegations against Ridge.

It was “adjudicated with an administrative closure,” according to the board’s records custodian, Heather Foster. It was never considered at a board meeting and doesn’t appear in board minutes.

Ridge denied the claim of misconduct.

He couldn’t remember the woman’s name but did remember “she was all tattooed up.”

They wrote him yet another letter that recommended he have a chaperone. But it was just a suggestion.

“While the Board cannot order Dr. Ridge to employ a chaperone because no discipline is being recommended,” the letter said, “the Board cautions him to take the recommendation for a chaperone seriously.”

Board let sex offender keep medical license

Every doctor should generally have a chaperone, according to the American Medical Association.

But it’s rare in Arizona to be compelled to have one.

Just seven doctors out of about 29,000 licensed in the state today are under that restriction, according to the state medical board.

Their vivid histories are buried in licensing files that patients would have to request ― the board is required by law to scrub its public website of a lot of doctor misconduct.

There’s Dr. Redentor Espiritu, who was accused in 2014 of inappropriately touching and attempting to kiss a partially disrobed patient while demonstrating areas where he proposed liposuction, according to a board order in his file. He couldn’t be reached for comment. His profile on the state’s website shows no record of the misbehavior, just that his license has unspecified “restrictions.”

There’s Dr. Charles Kelly II, who was accused in 2020 by three patients, one for “inappropriate performance of an examination,” one for “inappropriate contact during the course of an examination,” and one for “inappropriate conduct during the course of a colonoscopy,” his file with the board shows. He couldn’t be reached for comment. Patients savvy enough to use the board’s site can find the order to have a chaperone, among other restrictions, at the bottom of his profile.

And there is a registered sex offender.

In 2003, Dr. Thomas Francis went to a Tucson fast food restaurant with a sex toy to meet who he thought was a 14-year-old girl he had chatted with online, according to a court record and his medical board file.

Instead, he met police officers.

He pleaded guilty to one count of attempted luring of a minor for sexual exploitation, his licensing file shows. He was placed on “lifetime sex offender probation” and had to register as a sex offender, his file shows. Scottsdale police confirmed he is registered. He couldn’t be reached for comment.

The board revoked his license but in the same order stayed that revocation, leaving him free to practice, albeit with restrictions, including the chaperone.

“The determination to allow continued practice in this case was made prior to my employment with the board, and prior to the appointment of all of the current board members,” McSorley said in an email.

Francis offered no excuse for what he did, board minutes show. His attorney told the board he embarrassed himself, his family and his practice. But she argued this is “not who he is” and this is “an isolated event of extremely poor judgment,” the minutes show. He wasn’t sexually inappropriate with a patient.

When Francis spoke to the board, he underscored the narrow path he had to walk, including a lifetime of therapy. He said he would go to jail if he missed two sessions in a row.

The board voted to let him keep his license and put him on “indefinite probation.”

The board wrote him up once for not having his chaperone sign a patient’s chart. At the time, his wife, a nurse practitioner, was his chaperone.

Even so, he still has an active Arizona medical license.

A patient searching for him on the board’s limited public website would see no mention of his sex crime and no board actions.

Doctors make up two-thirds of board

The state medical board’s investigations are secret, and doctor misconduct is similarly hard for patients to learn about.

The board is forbidden by law from posting documents older than five years. It also is barred by a 2011 law from posting “advisory letters” that the board issues to doctors in response to complaints against them. It’s the most common action the board takes and these letters are expressly public records, if patients happen to know how to ask. The letters aren’t formal discipline but detail serious issues, including sexual misconduct.

The board is mostly insiders by mandate ― eight of 12 members must actively practice medicine. Five of the 12 have contributed to Arizona Medical Political Action Committee, associated with a doctor group that backed the law on advisory letters.

One board member, Dr. Gary Figge, appointed by former Gov. Doug Ducey, simultaneously served as a state medical board member and as the chairman of the PAC.

Figge declined to comment.

The board’s executive director offered a state handbook that instructs public officers on how to avoid conflicts of interest.

She also pointed to the board’s minutes, noting that “all deliberations regarding cases before the Board are discussed in public and a record of the discussions exists for public review.”

Despite that pledge of transparency, the board is hard to know about. Its investigations are secret. Audio recordings of board meetings started only in 2012, after much of its action on Ridge.

The board doesn’t track the nature of the complaints it gets, so it’s impossible to know how many doctors have faced sexual abuse accusations. The board provided a spreadsheet of doctors accused of sexual misconduct whom it took action against ― 24 since 2018. Six of the doctors kept their licenses, including one convicted in Mohave County court of “surreptitious photography.”

After The Republic asked about the gap in tracking complaints, the board’s director said in an email officials were “currently implementing a new database system which should be able to track and provide this information in the future.”

The Republic reached out to all 12 medical board members. The only one who replied was Dr. David Beyer. He declined to comment on Ridge.

“Certainly, the Board could do a better job with more resources,” he said in an email response to a question about their caseloads. “That is probably true of every state agency. But I remain proud of the work we have done.”

Forty-nine minutes after that message was sent, McSorley, the board’s executive director, instructed members to defer all questions about board business to her, according to an email obtained by The Republic.

McSorley largely declined to comment on specific cases, but offered a summary of the outcomes for Ridge, noting a jury acquitted him, and saying the board wasn’t allowed to revisit allegations that “underwent the scrutiny of the judicial process.”

“In addition, my observation of the Board is that they are a group of professional members committed to the protection of the public and take their roles very seriously,” McSorley said.

Find out more: How to check your doctor's history and other options for better health care in Arizona

’It might be my personality’

Younce left Casa Grande behind.

She got married, had three kids, and got divorced. She has a tidy suburban home with a lagoon-style pool in metro Phoenix, preferring the anonymity of a bigger city.

Younce studied for a career in health care compliance, securing a master’s degree and a new job in recent years.

She also learned she could look up doctors through the state medical board’s website. Ridge had lingered on her mind, and it occurred to her to look him up.

She found an order the board issued to Ridge.

He was accused by a 14th woman, J.W., who said he “inappropriately performed an abdominal examination by unnecessarily exposing her breasts,” the board’s order shows.

His attorney told the board in a recording of the March 2021 meeting: “While Dr. Ridge strongly denies doing anything that would have exposed the patient's breast, he does apologize for the obvious offense the patient took when he reasonably suggested she considered getting vaccinated against COVID and speak with her obstetrician for the welfare of her unborn child and her six other children.”

His attorney volunteered that Ridge would agree to have a chaperone for the rest of his career.

“Dr. Ridge has undergone thorough evaluations and assessments in which no evidence was found to support a sexual disorder diagnosis,” his attorney told the board. “In an effort to bring this matter to conclusion and to finish what remains of a 40-plus-year career, the proposed other action is appropriate.”

The board members had no questions. They entered a closed session, not available to the public, where they mulled legal advice.

When they returned, Dr. R. Screven Farmer opened the floor to the panel of experts tasked with keeping Arizona patients safe.

“Anyone wish to discuss this?” he asked.

They were silent.

“Very good,” he said.

He called for a vote, and they gave Ridge what his attorney asked for.

That included ordering him for a third time to have a chaperone, a requirement he was written up for violating before. Their order shows they did take note of several of the past complaints against him.

Ridge told The Republic it was his choice to have a chaperone.

After the latest accusation, the board put Ridge on permanent probation, meaning he has to have a chaperone for the rest of his career.

California passed a law that would require a doctor on probation to notify patients. In Arizona, patients have to dig around obscure recesses of a state website.

Even if patients go looking, they won’t find the whole story. Patients can see brief references to five board investigations in the probationary order posted on the board’s site, describing issues with two women and unspecified “allegations of inappropriate examinations of female patients.”

McSorley said the board is required by law to give law enforcement allegations of crimes, but also that the staff and board members get no formal training in determining what might be a crime.

The Casa Grande Police Department and Pinal County Attorney’s Office said they had no record of the board sharing the three complaints against Ridge that it received in 2003, 2011 and 2021.

“They probably should have been reported,” Jeff Sandler, the attorney who tried Ridge, said of the complaints to the medical board.

A reporter shared with Casa Grande police the board’s documents, in which three women identified by their initials accused Ridge of committing acts of sexual misconduct.

Police Chief Mark McCrory said the department did contact the board, but his department didn’t plan to act because the board didn’t see a crime and no victims came forward to the Police Department.

“We’re done with it,” he said. “We have real crimes we’re investigating here.”

McCrory later added, “We were not going to attempt to track down the parties who complained to the Board in an effort to talk them into filing police reports, when obviously they didn’t see the need to report anything to us initially."

Two police experts said they would do it differently.

“If I was the police chief, I wouldn’t blow it off like that,” said Roy Taylor, a former police chief in North Carolina who consults as an expert court witness on police procedure, including in Arizona.

A panel of doctors and political appointees aren’t law enforcement officers so they may not always recognize a crime, Taylor noted. He said he would try to review the board’s files and talk to the patients who complained of inappropriate touching similar to the complaints made against Ridge in criminal court in 1998.

A third expert, former Milwaukee Police Chief Edward Flynn, described how proceeding with a criminal investigation without a victim coming forward to the police is difficult. But he also said the complaints to the medical board appear to be allegations of crimes, and the board should have used its power to forward the complaints to the police, especially given the similarities between them.

In response to a summary of The Republic’s reporting about Ridge and the state medical board, Gov. Katie Hobbs sharply rebuked the board she is responsible for.

Her spokesperson blamed her predecessor, former Gov. Doug Ducey, and said they would try to fix problems The Republic exposed.

“This is a heart breaking story that represents a clear dereliction of duty from the Ducey-appointed majority on the Arizona Medical Board who fought against oversight of their own Board and refuse to take real action on these critical issues,” Hobbs spokesman Christian Slater wrote in an email.

“Gov. Hobbs knows we need to bring transparency and accountability to state government. She will work to reform the system to keep people safe, ensure Arizonans have access to the information they deserve about their medical professionals, and crack down on loopholes in medical licensing accountability.”

Ducey’s former chief of staff shot back, saying it’s time for Hobbs to take responsibility for state government.

Business was booming for Ridge.

In September, he was focusing on treating older patients and making a mint. In 2020, Ridge billed in the top 1% of his field in Medicare, the federally funded health care program mostly used by people over 65.

In the most recent year data is available, he billed $419,025.80. Most of the charges were for office visits.

In the September interview, he figured he would stick it out for another year and retire from his practice. He also said he practiced hospice care on the side and he wanted to keep providing that care until he needed it himself.

He said he sometimes wondered why so many women accused him of sexual misconduct. Not that he did anything wrong.

“It might be my personality,” he said. But, he said, he’s not going to change.

Ridge sold his practice to Optima Medical, which runs 15 clinics across Arizona. After talking to Ridge, The Republic asked Optima about him, and the company provided no response.

In December, Ridge said he retired.

“Had trouble negotiating my contract favorable to me so decided to retire. I am proud of my service to MY community and my patients but time to move on,” he said in a text message.

Pressed further, he simply texted back:

“Bye.”

Investigative reporter Andrew Ford exposes wrongdoing and prompts reform – do you know something he should write about? Email aford@arizonarepublic.com.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Arizona Dr. Michael Ridge was accused of sexual misconduct by 14 women