Mississippi casino country places a new bet — on an Amazon-backed wind farm

Even before Amazon publicly revealed its involvement in a utility-scale wind farm being built in north Mississippi, residents of Tunica County were already buzzing.

They had questions about what the project, the first of its kind in the state, might mean for one of the most impoverished regions of the country — and one prone to tornadoes.

“My first initial thought was: a wind farm in Mississippi?” said Marilyn Young, the director of the Tunica County Workforce Development Center, which connects residents with jobs and training programs.

After she received assurances that the towering turbines could weather dangerous storms, Young is excited about the hundreds of construction jobs accompanying the project, the clean energy the wind farm will produce and the property taxes that will come from the venture. Young hopes the money, an estimated at least $60 million in the coming decades, will help the county’s public schools, which have faced challenges including low test scores and aging facilities.

The wind farm project in Tunica County, owned by the Virginia-based energy company AES, will sell power to Amazon and is expected to generate enough electricity to run more than 80,000 homes starting early next year. That in turn could bring a financial windfall to a Mississippi Delta community that everyone agrees could use one, especially after the casino industry, which had buoyed the county’s fortunes, has faltered.

“Accepting this project here could move us to another level,” said James Dunn, who is on the Tunica County Board of Supervisors.

But not everyone is convinced that the project will improve life in a predominantly Black county where 27% of residents live in poverty. Although 300 workers are needed to build the project, AES said it expects it will hire only seven to 10 people to maintain and operate the wind farm once it opens.

AES’ initiative joins a burgeoning renewable energy industry in a state known for its political conservatism. Mississippi is part of a global clean energy market that had more than $1 trillion in investment last year and has sparked competition among local governments seeking the projects. The new sector, though, is running up against an old debate: whether to use generous tax breaks to woo big business.

“We gave away too much,” said Joe Eddie Hawkins, the county’s former road manager, who serves on the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta Levee District Board, which maintains some flood control projects in the region.

He supports renewable energy, because “climate change is crazy.” But he disagrees with the county’s approval of a decadelong tax break, which will allow AES, which bought the project from another developer, to pay a third of the property taxes it would otherwise owe.

“I really didn’t think that was a wise move for us,” Hawkins said.

In response to questions, Terrance Unrein, senior development director for AES, said that tax incentives are common for clean energy projects and that the Tunica wind farm is expected to bring “tens of millions of dollars to the taxing districts over the life of the project.”

Charles Finkley Jr., the president and CEO of the Tunica County Chamber of Commerce and Economic Development, said incentives are worthwhile to help attract businesses.

“We definitely want to be competitive in order to successfully recruit these types of projects into our community,” he said.

Finkley said the land where the wind farm sits would have brought in about $20,000 in property taxes over the next three decades, a fraction of the at least $60 million in taxes the county expects to receive.

Residents here know what it means to bring in big business; they’re also intimately familiar with what happens when those businesses’ promises begin to fade.

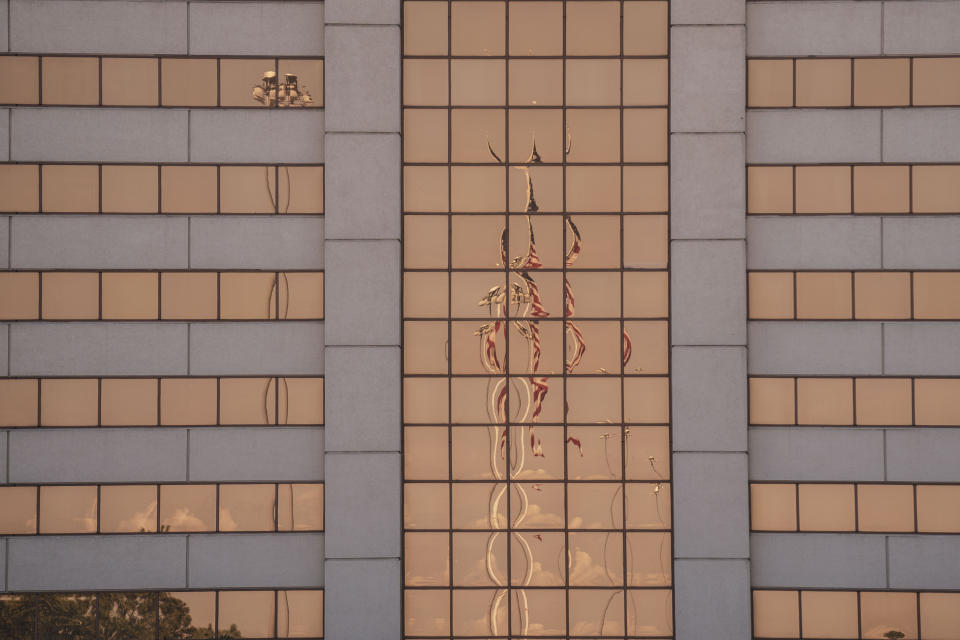

Tunica County was once known as one of the poorest counties in the country, until the arrival of casinos in the early 1990s helped transform it into the busiest gambling hub in the Deep South.

Gaming brought hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue to a county that has been beleaguered by poor housing conditions and underperforming public schools. But the casino industry has taken a hit over the years, because of increased competition from states like Arkansas. At least three casinos have closed since 2014.

During the pandemic, Dwight Mosley, who pastors a church in neighboring DeSoto County, helped run a drive-thru food pantry at an arena in Tunica County where long lines of cars showed how many families were overwhelmed.

Those dramatic sights are gone now, Mosley said, but a need for support remains.

“You’re looking at people making sacrifices,” he said.

Hawkins, the retired county road manager, hears echoes of the county’s historical problems in its issues today with education, health care access and rundown homes that look “the same way now as they did when the casinos first got here.”

As of 2022, Tunica was one of seven counties in Mississippi without a hospital. And although the school district has a B rating from the state, most students don’t achieve “proficient” scores on the state’s math and English exams. The district was one of dozens in the state with a teacher shortage last school year.

The new wind farm in Tunica County reflects a growing green energy sector in Mississippi. Just over the county’s border in DeSoto County, construction is underway on a solar farm with the capacity to provide electricity for roughly 21,000 homes. In 2021, Mississippi’s Republican-dominated Legislature approved allowing local officials in Tunica and Chickasaw counties to grant incentives for renewable energy projects.

That is happening even as the state’s leadership has protested some of the Biden administration’s priorities in dealing with climate change. No Republican members of the state’s congressional delegation voted for the Inflation Reduction Act, which included billions of dollars in tax incentives to fight global warming.

The attractiveness of economic development, though, and the opportunity to lower energy costs can cut through political battle lines.

“This project is an example of folks’ saying: ‘This is a great economic investment. This is going to bring jobs. This is going to bring tax revenue’ — and not doing culture wars,” said Caroline Spears, the executive director of Climate Cabinet Action, a political action committee.

Finkley, of the Tunica County Chamber of Commerce and Economic Development, is eager to see where renewable projects lead in a region that has grappled with economic challenges.

“These types of projects are not going to come in and solve all the problems with our communities,” he said. “But it’s a start. It’s a start and a step in the right direction.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com