Mizzou researchers use new methods to unlock secrets of ancient indigenous cultures in NM

A University of Missouri anthropologist who has been conducting research in New Mexico for 15 years is part of a team that is experimenting with new technology that may offer a more efficient means of identifying undocumented ancient Native American pueblos.

Jeff Ferguson, an associate professor in Mizzou’s Department of Anthropology, has spent much of the 21st century in western New Mexico tracking down the geological sources of the obsidian used by those indigenous people. His work involves studying the migration and social interaction patterns of those Native Americans and their connection to the pueblos that have been discovered.

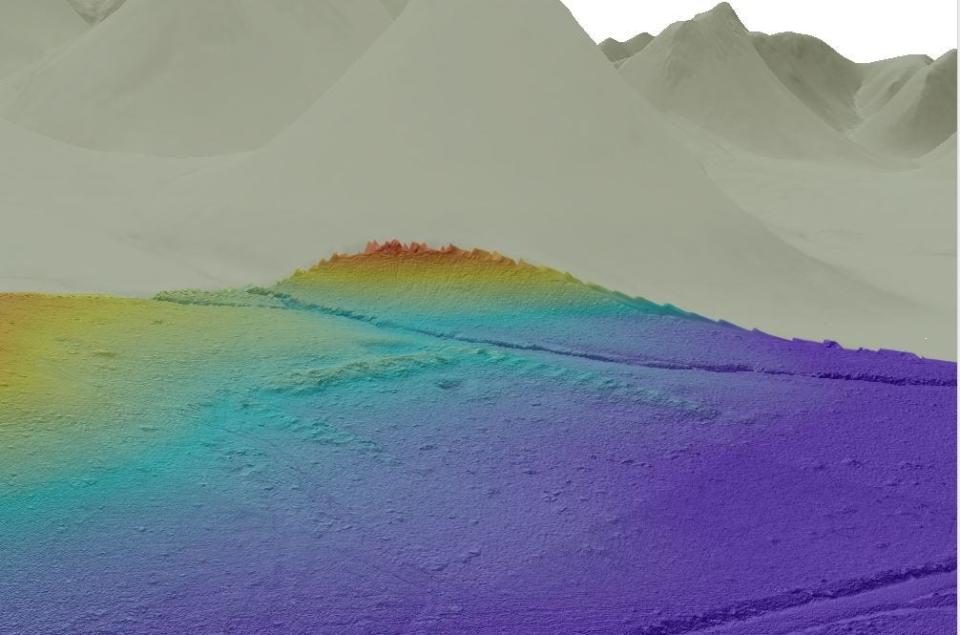

For the past two years, Ferguson and other researchers have been aided in their work by the use of Lidar — short for light detection and ranging equipment — and drones. Used together, the two pieces of equipment can be used to construct detailed images of the ground’s surface and help researchers identify ancient pueblos much more quickly than through aircraft or pedestrian surveys alone.

A University of Missouri news release describes lidar as a technique in which laser pulses are used to “map” the ground’s surface. The lidar equipment is mounted on drones, which can provide much closer and more precise access to the target area than airplane-based lidar.

The team has been working in the Lion Mountain area of western New Mexico, which is west-northwest of Magdalena.

“Among the archaeological sites discovered in the area is a massive pueblo likely built and occupied by immigrants from the large-scale abandonment of the Four Corners region, including Mesa Verde, in the late 13th century,” Ferguson said in the release. “Our research is focused on documenting the regional settlement pattern and understanding how the migrants coming from the north interacted with existing local populations. Using this technology, we aim to efficiently identify any sites not previously documented.”

Lidar has been used for many years during airplane surveys of large areas, and it remains very useful for researchers searching for ancient, undocumented, large-scale objects such as pyramids or even cities in the jungles of South America and Mesoamerica, Ferguson said during an Aug. 23 telephone interview from Columbia, Missouri.

But drone-based lidar can offer much higher-resolution imaging that can help researchers identify smaller structures, he said.

“That is relatively new,” he said. “In the last 10 years, it’s really changed the face of archaeology. The question we had is, can you use this on smaller sites such as one- or two-room pueblos?”

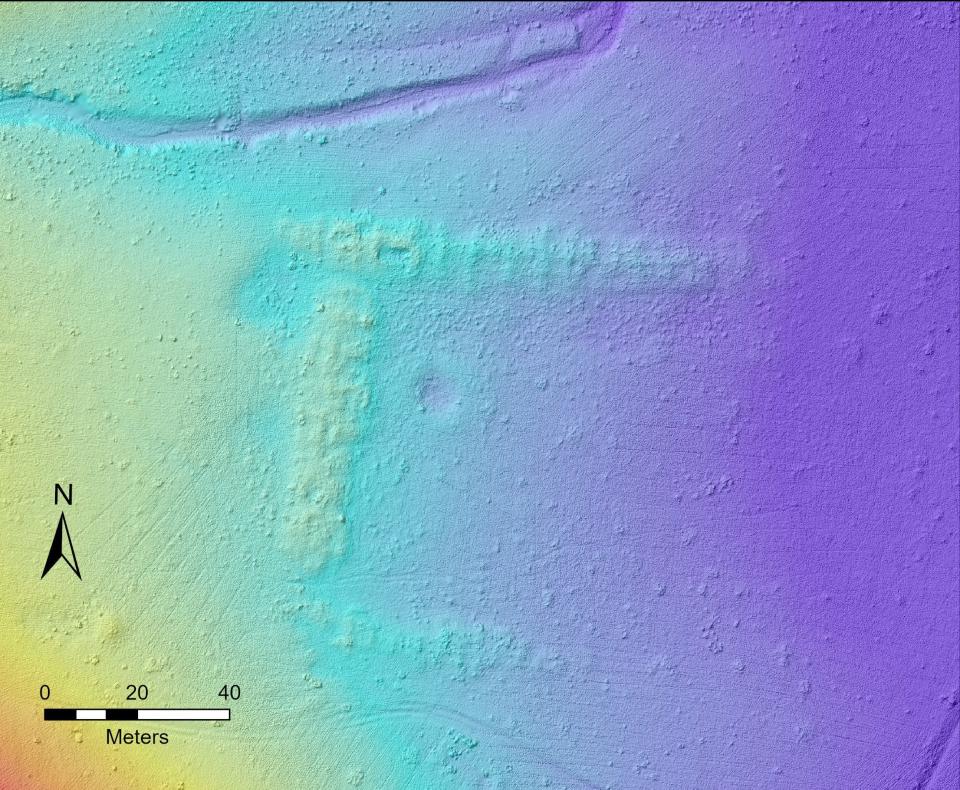

Ferguson said that after potential undocumented pueblo sites are identified during the lidar imaging, they are verified by researchers conducting ground surveys of the area – a process known as “ground-truthing.”

There was little data available about the Lion Mountain area before Ferguson and his team and some colleagues from the University of Arizona began working there with lidar and drones two years ago. He said the equipment is relatively expensive, and mastering it is very challenging.

“I think it’s incredibly difficult, at least for me,” he said, describing the process of earning a drone pilot certification as nearly as difficult as getting a pilot’s license.

Additionally, he said, learning the data processing and trouble-shooting skills needed to effectively operate the lidar is no easy task, either. It takes a great deal of expertise to massage and filter the data so that what you’re seeing is a clear image of the ground’s surface, Ferguson said.

Earlier this summer, Ferguson and his team were surveying a large valley approximately a mile north of the area in which they usually worked, he said. The lidar imaging they conducted of the area revealed several large humps. Even through the images weren’t terribly promising, Ferguson began surveying the area on foot.

Most of those humps turned out to be nothing more than sand hills, he said. But Ferguson soon identified a large ceremonial pit that turned out to be part of a 20- or 30-room pueblo that had never been documented. That’s a perfect example of why the ground surveys remain integral to the process, he said.

“If I had just looked at the drone-based data, I never would have seen that,” he said, noting the limits of Lidar despite the relatively high-resolution imaging it offers.

But in other cases, drone-based Lidar, with its bird’s eye view, can offer imaging superior to that of the human eye at ground level. Ferguson said one of his graduate students was surveying an area and noticed a notch in a hillside that he was certain was a Chacoan road — a network of ancient, finely engineered roads noted for their remarkable straightness in and around the Chaco Canyon area.

Believing the notch was a natural depression, Ferguson was dismissive of the idea that it was part of a road. But when his team conducted imaging of the potential road, “It was just as plain as day on the lidar,” he said. “ … That’s the kind of thing you can see that we couldn’t see before. You can see that this could be a beautiful addition to our survey projects.”

The Missouri researchers have been assisted in their work in the Lion Mountain area by a cultural resource advisory team from Zuni Pueblo, which claims the ancestral sites as part of its cultural heritage.

“They’ve been invaluable to work with in the field,” Ferguson said, explaining that the Zunis help the Mizzou researchers identify and understand what it is they are seeing.

In the news release, he described how the Zuni team determined that a small set of vertical stones at one site that had been placed in a box shape on the ground was, in fact, a shrine.

The Zunis also have a deep knowledge of local plant life that helps unlock the mysteries of how day-to-day life unfolded around the pueblos, he said.

At one of the sites Ferguson’s researchers will be returning to study in September, he said, the Zuni team will be there with drums to experience how the sound reverberates among the hillsides, he said.

“They’ve been very eager,” he said of the Zunis, adding that representatives of other regional indigenous groups, such as Laguna Pueblo, Acoma Pueblo and the Hopi Nation have expressed interest in joining the effort.

While the early returns from the Lidar-based drone imaging have been positive, Ferguson said it is too early to label the effort a success, as much more data is needed. But he did say the Southwest is the ideal location for testing it.

“In the Midwest, for instance, in most situations, much of the surface area has been plowed under,” he said. “But in the Southwest, a lot of that architecture remains on the surface.”

Mike Easterling can be reached at 505-564-4610 or measterling@daily-times.com. Support local journalism with a digital subscription: http://bit.ly/2I6TU0e.

This article originally appeared on Farmington Daily Times: Mizzou researchers use drone-based imaging to find ancient pueblos