MLK’s criticism of Malcolm X was likely fabricated. Duke played key role in discovery.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Jonathan Eig wasn’t expecting to make a significant historical discovery when he requested some of writer Alex Haley’s papers from Duke University’s Rubenstein Library last year.

The author was simply doing his due diligence as part of his research for his upcoming biography on Martin Luther King Jr. Since he knew Haley had conducted what is believed to be the longest interview with King ever published, Eig went searching for an original tape or transcript of the interview — the latter of which he learned was housed at Duke. He requested the university archives digitize and send him the transcript.

“I was really just covering all my bases,” he told The News & Observer..

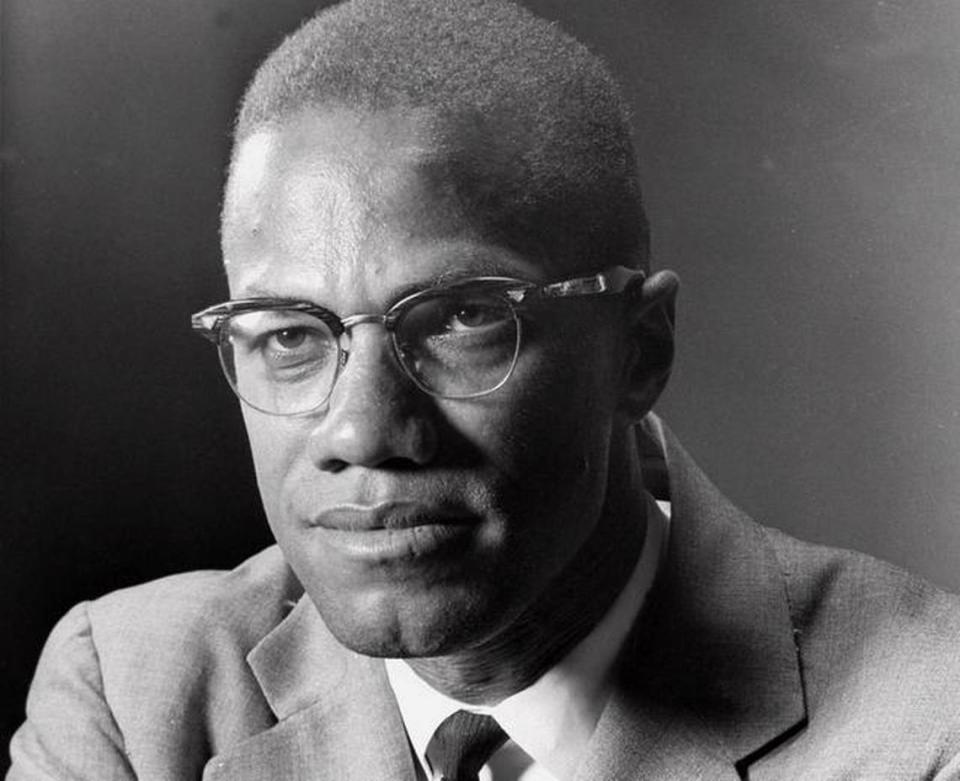

But as Eig studied the archives’ apparently unedited transcript of Haley’s interview with King, he “recognized immediately” the importance of what he had found: an apparent fabrication by Haley of King’s most famous criticism of Malcolm X, the Nation of Islam member who has generally been portrayed as an opposite figure to King in the context of the Civil Rights Movement.

In the apparently fabricated quote, King was quoted by Haley, in part, as saying that Malcolm X “has done himself and our people a great disservice,” including by performing “fiery, demagogic oratory in the black ghettos.” But in the version of the interview housed at Duke, King’s remarks on Malcolm X were significantly less harsh.

The quote has been “repeated over and over,” being taught in history classes or used in books to illuminate the two leaders’ differences and their relationship, Eig said.

“This is such an important quote, and to find that it was completely fraudulent was just shocking to me,” Eig said.

Haley is perhaps best known for writing “Roots: The Saga of an American Family,” the 1976 best-selling novel tracing his ancestry that later became an acclaimed television miniseries. He also collaborated with Malcolm X on the latter’s autobiography, which was published after Malcolm X’s death in 1965.

Eig’s discovery, reported by The Washington Post last week, only accounts for a paragraph in his new book, which will be released Tuesday, he said. But it will likely have implications for how historians view King and Malcolm X’s relationship moving forward, as well as how scholars view Haley’s work, which has previously been questioned for plagiarism and other fabrications.

Locally, though, the discovery is just one example of how the papers and documents housed in Duke’s archives assist scholars and researchers in their work.

“People make discoveries like this all the time,” John Gartrell, director of Duke’s John Hope Franklin Center for African and African American History and Culture and a curator at Rubenstein Library, told The N&O. “They’re not always as groundbreaking as this relationship between King and Malcolm X, but, you know, learning something about your family or reading something that’s just 100 and 200 years old can really be a life changing experience.”

How Duke got the Haley interview

Gartrell said Duke obtained the Haley interview by purchasing some of the author’s papers through a book dealer in 2008. Though the university primarily obtains documents and materials through donations, Gartrell said, funds are available to purchase materials when necessary.

The John Hope Franklin Center, which is named for the late, influential historian, and Rubenstein Library have “a general interest in collecting, preserving and making available primary sources” related to the African American experience and history, Gartrell said. The collection represents “a constellation of materials that are kind of interrelated to each other,” he said.

The Haley papers were attractive to Duke, Gartrell said, because they “certainly would fall under that umbrella of the kinds of materials that we collect.”

The specific transcript from which Eig made the revelatory discovery about King and Malcolm X is considered the long-form, original copy of Haley’s interview with King that later became a question-and-answer-style article published in Playboy in 1965. The interview is considered to be the longest with King ever published and extensively covers King’s thoughts on the Civil Rights Movement, including a direct question about King’s opinion of Malcolm X.

The published interview, as analyzed by Eig and separately by The Washington Post, contains what appear to be both fabrications and rearranged, out-of-context quotes, compared to the original transcript housed at Duke.

For example, The Post reported, King’s quote in the published interview stating that Malcolm X had brought “fiery, demagogic oratory in the black ghettos” was part of a response to a different question earlier in the interview that was not directly related to a question about Malcolm X. Another part of the published quote, in which King was quoted as saying that Malcolm X had “done himself and our people a great disservice,” does not appear in the original transcript at all, The Post reported.

Importance of primary sources

Because few quotes by King speaking about Malcolm X exist, Eig said, the quote published in Playboy has been used to illustrate the men’s relationship throughout history, often appearing in books or other texts about the pair to further the idea that they were opposites within the Civil Rights Movement.

But in researching for his biography of King, Eig wanted to get to the source of the quote and verify it for himself — something he does regularly when researching — and the transcript housed at Duke allowed him to do so.

“A big part of what I try to do as a biographer is get to the primary sources and question everything,” Eig said. “You know, just because something is in a book doesn’t mean that you should repeat it in your book, and every chance I get to knock down one of those myths or correct one of those errors is important.”

Primary sources, Gartrell told The N&O, are original documents and materials that offer “a first-person account or a window into what the original thoughts and ideologies, perspectives, stories of the people that live in a particular time in history.”

“Most people engage with history through what we call secondary sources, which are essentially books that are written by people that are talking about a specific timeframe,” Gartrell said. “The best kind of histories rely on primary sources to tell that story, and by using primary sources, you actually become the person who’s doing the observation.”

By storing primary sources in publicly accessible places, such as the archives at Duke, they are made more widely available to revisit and reexamine history, and sometimes discover new interpretations entirely, Gartrell said. In theory, if Haley’s papers had remained in an attic or basement, where so many family belongings are generally stored, Gartrell said, it would have been more difficult — or perhaps impossible — for Eig to make his discovery.

“The time and investment that archivists make in describing and collecting material, and then making those materials available to the general public, allows for people like Jonathan to revisit a perspective of history that we were once taught and give it new eyes and new perspectives based on the sources,” Gartrell said.

Gartrell said the archives at Duke serve a “very diverse” base of users, from undergraduate students at the university, to scholars and historians, to people researching their family’s history and genealogy, and all are welcome to research and make discoveries — big and small. Materials are available to be viewed in-person or through a “virtual reading room,” an option made popular during the pandemic.

“Even if it doesn’t shift the narrative of our understanding of the Civil Rights Movement,” Gartrell said, “it can be a very personal experience for anybody who wants to come in.”