MO House committee OKs bill giving Kanakuk sexual abuse victims more time to file lawsuits

When children are the victims of sexual abuse, it can take years to process the trauma and seek legal action against the perpetrators.

Under current Missouri statute, those who were sexually abused as children must seek legal recourse by the time they are 31 years old or “within three years of the date the plaintiff discovers, or reasonably should have discovered, that the injury or illness was caused by childhood sexual abuse, whichever later occurs.”

Rep. Brian Seitz, R-Branson, has once again presented a bill to increase that statute of limitations by 10 years, meaning that a victim must file by the time they are 41 years old.

“Through no fault of their own, children who may have been abused in the past are being victimized again by not being allowed to hold their perpetrators to account in civil actions,” Seitz said.

According to a 2020 report from Child USA, a think tank for child protection, 25% of girls and 17% of boys in the U.S. will be sexually abused before they are adults.

“There was a study done of over 1,000 sexual abuse survivors, and the average time of a reporting of child sexual abuse, especially among males, is age 52,” Seitz said.

Although Seitz said he would like to see the legislation go further, he realizes that “there are some things that we can do and some things that we can't do.”

Seitz’s legislation received unanimous approval from the Missouri House Judiciary Committee, for the second year in a row. It also unanimously passed the Missouri House during the 2023 legislative session, but it failed to make it through the gridlocked Missouri Senate before session ended.

Survivors of childhood sexual abuse at the Branson-based Kanakuk Kamps testified in support of the bill. Family members of children abused at the camp also testified on behalf of loved ones who committed suicide due to the trauma they experienced.

Elizabeth Phillips, the sister of Trey Carlock, a child sexual abuse victim of Kanakuk who died by suicide in 2019, shared his story of abuse at the hands of former Kanakuk employee Pete Newman, who was found guilty of molesting nearly 60 children. Newman is currently serving two life sentences plus 30 years in a Missouri state prison for child sexual abuse.

“Pete wasn't the only one who abused my brother,” Phillips said. “Trey was abused again by Kanakuk and its agents, who harassed and gaslit him in a re-traumatizing legal process that ended in a settlement achieved by fraud, which included a restrictive NDA.”

This was the case with many victims at Kanakuk, according to Phillips, who said 16 victims of childhood sexual abuse at Kanakuk have now committed suicide. An extended statute of limitations would give these victims more time to process their trauma before reliving it in a lengthy court battle.

“The short statute of limitations here in Missouri also robs victims and furthers the abuse,” Phillips said. “Since Missouri's draconian statute of limitations requires victims of child sexual abuse to file civil action against a liable institution by the age of 26, victims are forced to relive their nightmare when they're just trying to survive and heal.”

More: Survivors, ex-employees say unreported abuse at Kanakuk camps in Branson spans decades

Keith Dygert also suffered sexual abuse at the hands of Pete Newman when he went to Kanakuk as a child. Although others had accused Newman of abuse in the past, no action had been taken to remove him from his position working with children.

“Here I am after years of abuse, years of counseling, years of emotional turmoil and years of nightmares I have no control over,” Dygert said. “Perhaps the most disgusting part of my story is that it could have been prevented.”

Dygert took legal action against Kanakuk, and by going through that process, he saw firsthand the emotional turmoil enacted by being forced to relive the sexual abuse, especially against a well-connected institution in his home town.

“It was grueling, long and difficult,” Dygert said. “I can easily understand why so many victims never choose to go through with it.”

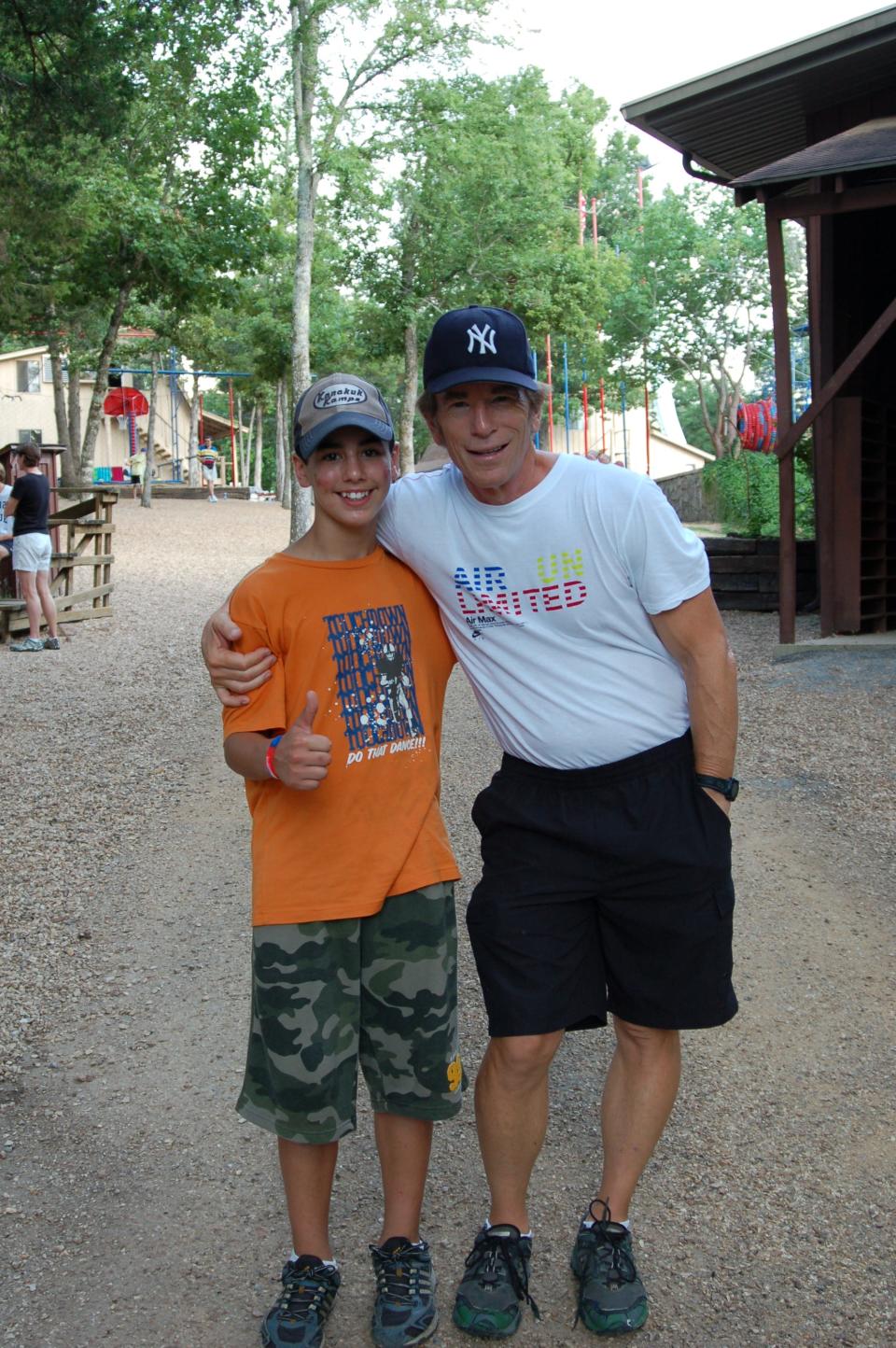

Joe Alarcon shared an equally heartbreaking tale of the abuse of his son, Ashton, at Kanakuk. Alarcon sent his son to the camp for several years, and, at the encouragement of Kanakuk CEO Joe White, he consented to allow Ashton to stay a few extra days at Newman’s request. White said Newman did this frequently and all was well, but Ashton was sexually abused during that stay.

“I felt like I had handed my son over to the devil and guilt that I still live with today,” Alarcon said. “I'm his father, and I allowed Joe White and Pete Newman to fool me, and my son paid the price.”

The emotional turmoil wrought on his family by the ordeal led to the death of his son Preston, who internalized the suffering of his brother, Alarcon said. Preston became anxious and depressed, and in 2022, he took what he thought was a pain pill to help him sleep. It turned out to be fentanyl, and Preston died that night.

“I keep asking myself, ‘How much more do we have to keep paying?’ My heart is broken and I do not know how to heal,” Alarcon said. “My family is devastated and the pain does not stop.”

Alarcon also hopes to see some action taken by the Missouri General Assembly to provide victims time to process their trauma before being forced to relive it in court by enacting a longer statute of limitations.

“I can stand here before you and testify how hard it is to say, ‘Hey, you touched me. Hey, you hurt me, and that was wrong.’ Those simple words are so vital to one's healing,” Alarcon said. “This bill would allow victims the time that they need to do just that. I asked you to please pass this bill and be the voice for the victims until they can speak for themselves.”

Mark Habbas, a lobbyist representing the City of Branson, spoke in support of the legislation on behalf of Branson Mayor Larry Milton.

More: Branson men, both 34, describe Kanakuk sex abuse, call for camp to be held accountable

Although most public testimony was in support for the legislation, some witnesses representing the interests of various insurance agencies spoke in opposition to the bill.

While speaking in opposition, Rich Aubuchon, representing the Missouri Civil Justice Reform Coalition, acknowledged the atrocity of the crimes committed against victims and their families who spoke up at the public hearing.

“If you were not moved by the testimony of those before me, you don't have a human heart,” Aubuchon said. “Let me let that sink in. These are crimes that we're talking about, and they're terrible.”

However, Aubuchon pointed out the impact that this could have on insurance rates for businesses like daycares and camps that aren’t bad actors, which could potentially force some to shut their doors because of skyrocketing prices.

“Not every employer is a bad employer. Please just remember that not every employer is a Kanakuk,” Aubuchon said.

“I'm a dad. I rely upon daycares to be able to go to work. I rely upon camps to be able to fill summers so that I can go to work, and I'm not alone,” Aubuchon said. “I'm telling you that there will be vastly disparaging impacts upon those companies that rely upon insurance to be able to have their business open and protected.”

This article originally appeared on Springfield News-Leader: Missouri bill would extend statute of limitations for child sex abuse