In modern times of protest, James Baldwin’s meditations on America and race still resonate

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 2020's Black Lives Matter moment, protesters by the tens of thousands flooded streets from Minneapolis to Louisville to Atlanta to Kenosha shouting at America to look at itself — to confront its lies about race.

Arguably, no writer has ever made that demand more forcefully, passionately, or eloquently than James Baldwin. More than 33 years since his death at age 63, Baldwin continues to give voice to our times. Many of today’s most prominent intellectuals and writers, including Ta-Nehisi Coates and Jesmyn Ward, published works that channel Baldwin.

Both Ward’s "The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks About Race" (2016) and Coates’ "Between the World and Me" (2015) are direct rifts on Baldwin’s 1963 iconic collection of essays "The Fire Next Time," a searing critique of the racial issues that have distorted and turned ugly the American Dream.

Baldwin even seemed to foreshadow our current fraught political moment — the aftermath of the 2020 election that spawned the deadly U.S. Capitol riot: “A civilization is not destroyed by wicked people; it is not necessary that people be wicked but only that they be spineless,” he wrote in "The Fire Next Time."

“Jimmy lived in the present. He spoke to the ‘now,’ ” said the internationally acclaimed writer and poet Quincy Troupe, explaining why the words of his close friend still resonate. “He was unflinchingly honest, always truthful, always blunt. … He’d tell it like it is and never minced words.”

Eddie Glaude Jr., chairman of the Department of African American Studies at Princeton University, agrees. His recently published book "Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons For Our Own," shot up best-seller lists in 2020. Of Baldwin, he says: “Without question he was the pre-eminent American writer on race and democracy. … Here you have this queer Black man who spoke courageously and truthfully to the circumstances of Black folks, of all Americans…His life was so on point, so in the moment.”

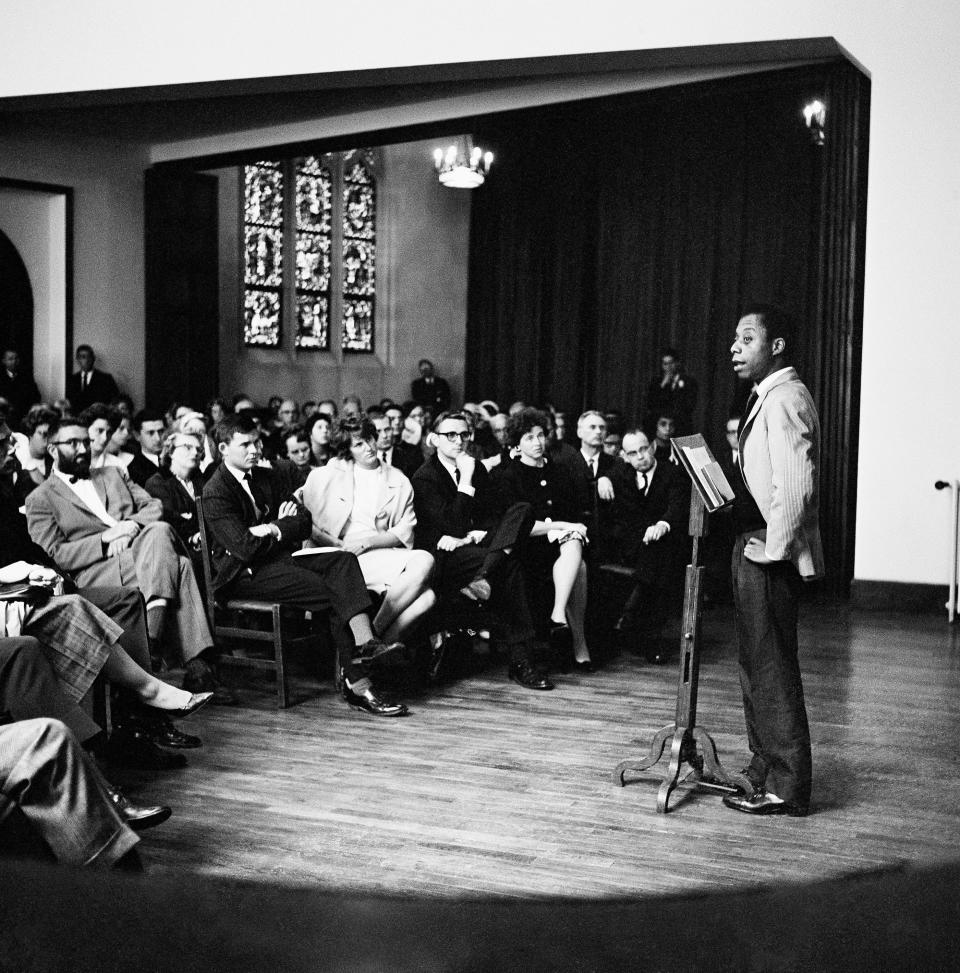

It was Baldwin’s willingness to accept the risks that come with unapologetic honesty — in his own words, “to bear witness” — that made him one of the foremost advocates for racial and personal freedom. This wisp of man — big-eyed, gap-toothed and all of 5-foot-6 — called out America’s hypocrisy and depravity again and again, shaming its need to cling to its creation myth of freedom and democracy while ignoring the racism and genocide at its root.

More: Black History Month 2021: The only way forward is through, together

Sitting for an interview with Esquire magazine editors in July 1968, with the nation rocked by riots in the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination, Baldwin was asked: “How can we get Black people to cool it?” Baldwin replied: “All that can save you now is your confrontation with your own history….Your history has led you to this moment, and you can only begin to change yourself and save yourself by looking at what you are doing in the name of your history.”

Baldwin’s bearing witness to the anger and angst of the civil rights struggle that metamorphosed into the Black Power movement made best-sellers of his books of the late 1950s and '60s — and again in the 21st century. Raoul Peck’s 2016 Oscar-nominated documentary "I Am Not Your Negro," which explored America’s racist history based on Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript "Remember This House," speaks to his timelessness. So does the award-winning 2018 film "If Beale Street Could Talk," adapted from Baldwin’s 1974 novel of the same name.

Baldwin’s famous, iconic 1965 Cambridge University debate with William F. Buckley, the father of the conservative movement was reimagined for the 2020 March on Washington Film Festival. Harvard University professor Khalil Muhammad and conservative political commentator and writer David Frum tackled roughly the same motion put to Baldwin and Buckley 55 years earlier: "Is the American Dream at the expense of the American Negro?"

The original debate, along with Baldwin’s speeches and film interviews, receive millions of online views each year. And historians and scholars by the score continuously mine the life and works of the man Malcolm X knighted as “the poet of the revolution.”

Glaude noted that at one point in his life Baldwin was a child preacher. In a sense, he said, Baldwin never left the pulpit. “He got the contradictions at the heart of America. …Baldwin has always been the key figure in helping us understand this American project.”

Baldwin keenly observed that every time America is on the precipice of fundamental change — as it is now after its continued racial divisions have been laid so bare — it recoils and reasserts “the lie at the center of America’s self-image: that white people matter more than others.” Those times according to Glaude, include Reconstruction, the civil rights movement, and most recently, the election of Barack Obama. “Baldwin said that the ‘horror is that America changes all the time without ever changing at all.’ ”

Born into the hardscrabble that was Harlem in 1924, young Baldwin felt the sting of rejection first from an unloving stepfather and soon after from a country that diminished and demonized him solely because of his race. In 1948, at age of 24, he fled penniless and unpublished to Paris. In a 1984 interview he explained his escape to Paris saying, “It was not so much a matter of choosing France. It was a matter of getting out of America.”

![Actor Marlon Brando, right, poses with his arm around James Baldwin, author and civil rights leader, in front of the Lincoln statue at the Lincoln Memorial, August 28, 1963, during the March on Washington demonstration ceremonies which followed the mass parade. Posing with them are actors Charlton Heston, left, and Harry Belafonte. (AP Photo) ORG XMIT: APHS200 [Via MerlinFTP Drop]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/IWTfwW5NkjIo2mZsRG.L2Q--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTY1Mg--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/usa_today_news_641/146e62aac9306aa11d4a4cdbaddfb53d)

But Baldwin never gave up on America, crossing and recrossing the Atlantic Ocean to immerse himself fully into the civil rights struggle and the Black Power movement. He returned not only to confront but to recharge and reconnect, pointed out Troupe, who as young writer would often meet Baldwin at Mikell’s, a Harlem jazz club. “Jimmy would come to town and call everyone to the spot.”

He remembered Baldwin, chain-smoking, a scotch or bourbon in his hand, holding court talking politics, talking about writing, or just talking smack. “Jimmy was physically a small guy, but he didn’t take (crap) off nobody…Everybody loved his courage, his writing, he was just a beautiful brother," Troupe says.

Subscribe: Help support quality journalism like this.

Nearing the end of his life, Baldwin shared with Troupe that he felt like a “broken motor”, issuing the same warnings about racism over and over again. Troupe had gone to Saint-Paul-de-Vence in the south of France in November 1987 to visit the writer just weeks before his death. As Baldwin expressed in "The Last Interview", as told to Troupe: “You know I was trying to tell the truth … It’s been said, and it’s been said, and it’s been said. It’s been heard and not heard. You are a broken motor.”

Troupe said that even weakened by stomach cancer and bedridden Baldwin remained insistent in his demand of honesty from America. “Jimmy loved America, but he hated stupidity and racism.”

Baldwin had that tenacious determination, that unbreakable will and that doggedness to go toe to toe with America because at his core he was fighter, Troupe said. He said that resolve came from Baldwin being bullied in the streets of Harlem as a boy, a story the author shared with Troupe in "The Last Interview."

“Well, if you wanted to beat me up, okay. And, say, you were bigger than I was, you could do it…but you gonna have to do it every day. You’d have to beat me up every single day. So, then the question becomes which one of us would get tired first. And I knew it wouldn’t be me.”

Glaude said that in Baldwin’s nearly 7,000 pages of writing the demand for honesty is the through line. “There was always his insistence on being honest with ourselves. And this honesty will open up space to imagine ourselves otherwise. James Baldwin set the stage for us being together in a way that is different and more just.”

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Carl Chancellor is managing director of editorial at the Center for American Progress. He is writing a historical novel about the 1935 Italo-Ethiopian War.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Author James Baldwin resonates with new generation of activists