Modern Vascular prioritized profits, faces claims patients were maimed or died

Editor's note: After this investigation was published by The Arizona Republic in October, the Department of Justice filed a civil complaint against Modern Vascular, quoting in part from The Republic’s story. References to the DOJ have been updated to reflect that complaint. Modern Vascular has disputed the claims in the complaint. The government’s filing focused on claims Modern Vascular defrauded millions of dollars from Medicare, and an attorney for the company noted the government didn’t make its own claims of patient harm or unnecessary procedures. However, such claims were made by other involved parties as detailed in this story and two legal experts confirmed they remain active.

The patient didn’t want to go through with the surgery.

He called the office of Dr. Scott Brannan.

“I’m in a lot of pain,” Brannan recalled him saying. “I don’t think I can make it in.”

The patient was in his late 60s, Brannan said. He slept in a recliner because when he laid down, his legs cramped.

Brannan got on the phone.

He stressed the situation was bad.

The patient needed to come in right now.

Then, Brannan jumped in his minivan, a Dodge Caravan with the license plate WIREDOC.

He drove to the man’s Gold Canyon home on the outskirts of metro Phoenix. Brannan brought the patient to his clinic and performed his handiwork, later taking the man home.

Brannan is an interventional radiologist. He threads angel hair wire into the arteries of a leg to probe the body’s plumbing and clear clogs, down to some of the tiniest vessels near the toes.

Brannan has picked up patients a few times at their homes. It’s an unorthodox practice he says is motivated by compassion. He wants his staff to see a doctor doing humble tasks.

A former employee, however, saw it as Brannan trying to pack in as many surgeries as he could.

The former employee’s skepticism is echoed in seven of 12 lawsuits filed against the company Brannan works for and in interviews with current and former staff members. They portray a pursuit of profits that challenges the purported altruistic mission of the chain of clinics where Brannan rose to stardom: Modern Vascular.

Brannan’s zeal propelled him from a trailer home to medical school, from repeated arrests to national prominence. His billing boomed in the five years Modern Vascular expanded from metro Phoenix to 17 locations in 10 states. It appears that after The Republic published its investigation into Modern Vascular in October, the company closed its Tucson, Arizona, and Albuquerque locations, two of the sites where lawsuits alleged misconduct occurred.

The company claims to prevent amputations. But Modern Vascular is plagued by allegations, some in lawsuits, that its profiteering approach caused injury and death after unnecessary surgeries.

Modern Vascular cashes in on vulnerabilities in American health care, where the profit motive challenges a doctor’s pure commitment to patients under the Hippocratic oath. The company solicited investments from referring podiatrists and paid them dividends. It collected six-figure rebates from a device manufacturer, strategized on choosing a billing code to pump up revenue, and — at least at one clinic — pressed for half of the patients who came for a consult to get a procedure, according to company documents and court records reviewed by The Arizona Republic.

Modern Vascular claims its clinics have done thousands of procedures, and its complication rate is low. When asked, the company offered no data to support its claim.

It may not be possible to quantify the consequences of Modern Vascular’s profit-driven approach or compare its complication rate with peers', because injuries during procedures at vascular clinics like theirs aren’t required to be independently tracked.

Brannan detailed how he and his company are exceptional, including an occasion they did pro bono work. But he also said health care is dominated by amoral market mechanisms.

“Most of the public is not aware of how much of a business all of medicine is,” Brannan said.

He’ll often tell loved ones to resist their doctor’s referrals to specialists for exotic procedures, he said.

“In most cases, I tell my family, or I tell friends that trust me, please don't,” Brannan said. “Please don't go down this road. This is how the system works: It's given legitimacy because there's rigorous certifications and a rigorous process of education that's around it. But you're being Amwayed. You’re being multilevel marketed, right now, whether you know it or not.”

Victoria Garcia, 66, of Coolidge, Arizona, lost a leg after a Brannan procedure. But he pumped his biceps for her and later convinced her to have another, she said. Garcia’s attorney provided a copy of a lawsuit she filed in October. It claims Brannan and his company billed more than $300,000 and performed “medically inappropriate and unnecessary vascular procedures that caused Ms. Garcia to suffer the loss of her remaining leg to amputation.”

The vascular surgeon who amputated Garcia’s second leg, Dr. Brett Siegrist, told The Republic she did not need Brannan’s second procedure.

“I fully expect to see complications in my practice related to vascular procedures from other doctors,” Siegrist said. “I can say there’s too many coming from Modern Vascular.”

Garcia is now stuck at home.

“I'll sit on my bed, cross my legs — well, my stumps,” she said, “and I'll sit there and cry.”

“Every time that there's an amputation, it's a huge loss, for the patient and for me,” Brannan said of Garcia. “I feel like it's a failure. But there are certain, unfortunately, still, there are certain cases that recur, and I'm not sure exactly why they happen.”

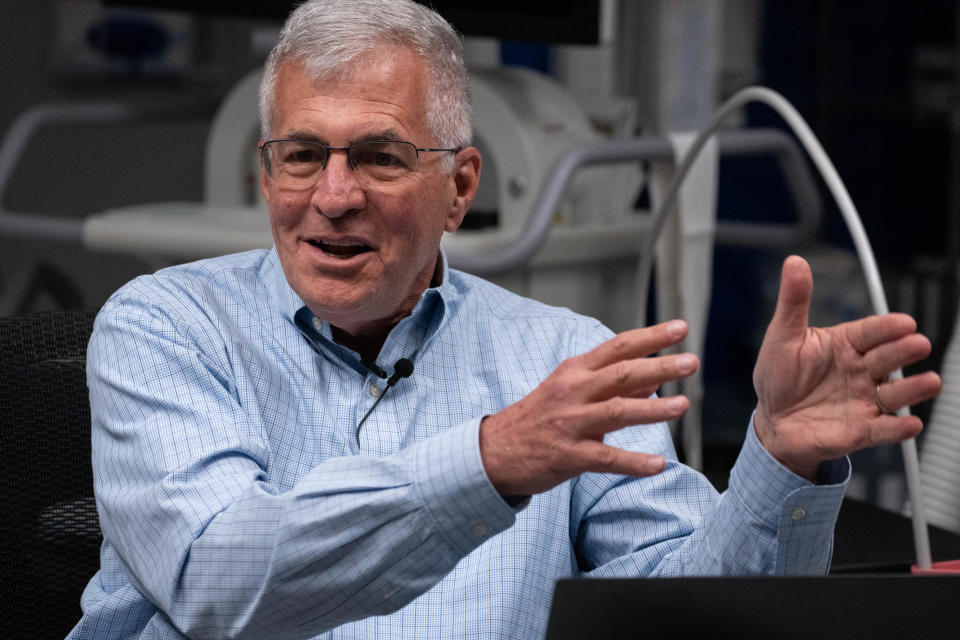

A lot of Brannan’s life is documented in court records and police reports. His career and dealings with Modern Vascular are illuminated by lawsuits and described by patients, Brannan’s peers, and former and current Modern Vascular employees including upper management. The Republic interviewed Brannan for more than 16 hours.

He’s intelligent, charismatic and erratic.

Publicly, he boasted:

“I've done more of this than anybody on the earth,” Brannan said in an interview with The Republic.

But when he gazed into his reflection in the bathroom mirror, his ex-wife said in court, he tore himself apart:

“I hate you! I f---ing hate you!”

Moving fast even when misguided, Brannan has seen prison, a Paradise Valley mansion and a vision of his own damnation:

“When I die," he once wrote, "it was revealed to me, I will go to hell for the choices I have made.”

Pushing the bounds

Brannan and others at Modern Vascular mostly treat a narrowing of blood vessels called peripheral artery disease, which especially afflicts people with diabetes and former smokers. They market their work as cutting edge, using smaller versions of wire and other familiar tools to reach tiny blood vessels in the feet.

An expert doctor can feel subtle resistance in the wire. It’s like passing a thread through the eyes of 20 needles. Too much pressure or haste and the wire could tear the artery.

A doctor’s mistake could cost a patient their leg or their life. So the surgery is only worth doing when the potential rewards outweigh the risks. For example, surgery could be warranted if someone is in pain even when they’re not walking, an expert explained, or if they have a wound on their foot that won’t heal.

Brannan said he’s good at his craft because he has a lot of experience derived from an “irrational expectation of perfection.”

"I keep going when other people would sometimes stop,” he said.

Brannan ranked seventh of more than 1,600 doctors billing for similar procedures, the most recent publicly available Medicare data showed. Three other Modern Vascular doctors also ranked highly.

"The data suggests that the company is encouraging high billing practices and at least a few of their physicians are participating in that,” said Dr. Caitlin Hicks, an associate professor of surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine who has studied overuse of vascular interventions. She said she has observed similar patterns of overuse in her data.

Brannan and other Modern Vascular doctors might rank highly because their company pushes invasive procedures rather than conservative treatments – a strategy that wastes public money and puts patients at risk, according to a lawsuit alleging fraud filed in 2020. That lawsuit and two similar suits were kept under seal until they were joined in September by the Department of Justice. One claimed government programs paid millions for unnecessary procedures by Modern Vascular.

“We do a lot of amazing work,” Modern Vascular’s founder and chairman Yury Gampel said when the fraud lawsuits became public. “We save limbs every single day in all of our clinics.”

The DOJ has investigated Modern Vascular for at least a year, according to a Q&A the company shared with its investors, obtained by The Republic. In December, the department filed its own claims that Gampel and his company engaged in a $50 million Medicare fraud scheme. The DOJ's claims partly corroborate and quote from The Republic's investigation.

An attorney for Modern Vascular denied the DOJ's accusations and noted the DOJ didn’t make claims about medically unnecessary procedures or patient harm. However, those claims were made by other parties involved and remain active, according to two Arizona law professors. The Modern Vascular attorney didn’t respond to an opportunity to comment on this story being published by USA TODAY.

Most of Modern Vascular’s clinics remain open.

In addition to the lawsuits joined by the Department of Justice, 12 lawsuits filed on behalf of patients detail claims of harm to Modern Vascular patients. Another four people claimed harm in interviews with The Republic.

At least four people lost limbs, and three of those individuals sued. Modern Vascular was blamed for wrongdoing in connection with two patients' deaths, other suits allege. At least six patients said in lawsuits the procedures were unnecessary.

Nine of the 12 lawsuits are still open, and Modern Vascular has denied almost all the claims in court. One case settled under confidential terms, according to an attorney who sued a Modern Vascular doctor. Another attorney said he dismissed his lawsuit, which was related to the death of a Modern Vascular patient, because a toxicology analysis wasn’t done on the patient. An attorney involved in the third dismissed suit said he would neither confirm nor deny the case was settled.

At least four people were hurt under Brannan’s care, according to lawsuits. Brannan denied the claims in court in three of the cases. Two of the cases are ongoing. One case was settled, Brannan said, and one was dismissed.

At a previous clinic Brannan worked at, one of his patients died, according to court documents and testimony before the Arizona Medical Board. To head off a malpractice claim, Brannan said in a deposition, he paid the patient's daughter in installments totaling $10,000.

Modern Vascular clinics in Arizona were cited by the state 23 times, for problems /including lack of quality control, failure to toss expired medication and failure to properly document when a patient died two days after a Modern Vascular procedure, state records show. The clinics filed plans for correcting the issues, according to the records.

Sometimes when Modern Vascular patients are in trouble, the staff calls 911. The company says that’s common practice. Employees have done that at least 30 times at clinics in five cities, according to records of emergency calls to their addresses. That includes a patient who emergency responders found "bleeding out" in the Tucson operating room.

Vascular surgeon David Terry said in one of the ongoing lawsuits joined by the Department of Justice that Modern Vascular’s Glendale, Arizona, clinic “engaged in a pattern of performing unnecessary interventions on patients.”

A bedridden patient died of an unnecessary procedure performed byBrannan, the lawsuit said.

“They are a threat to this community,” Terry said of Modern Vascular in an interview.

'The all-American boy next door'

Brannan hid in his bedroom. He locked the door. A bolt of visceral fear crackled through him.

A hearing before the Arizona Medical Board in August had gone badly, and then he received an email from a reporter asking to talk about his life, divorce, lawsuits and criminal record.

His corporate attorney told him not to talk.

But he didn’t let that stop him.

Among the first things he said to The Republic after he emerged from his shelter to answer for his past: “I'm coloring way outside the lines.”

To help explain who he is, Brannan proposed a tour of his hometown. He whipped his white Chevrolet Suburban north from Scottsdale, reporter riding shotgun.

He told his life story, conceded some mistakes and hoped his better qualities would redeem him. He texted and took calls while driving. He apologized aloud to the honking cars he cut off. He has a big blind spot.

As for trouble with the Arizona Medical Board, he said, we’ll talk about that later.

He’s 5 feet 10¾ inches, 209 pounds with a 34-inch waist. He has no military background, but he does have military arms. He wore a tight gray T-shirt with an American flag stretched over the right shoulder. He said he has taken prescribed Ritalin or Adderall since high school and he got buff with the help of anabolic steroids.

Brannan depicted himself as a poor country boy. He said he has long fought a gnawing feeling of illegitimacy. He has overachieved but also has exaggerated his achievements.

"I went and got a diploma – two diplomas – from Yale, one diploma from Harvard,” he said, stretching the truth about his residency and fellowship.

As a kid, Brannan crammed into a single wide trailer with his mother, three brothers and often a cousin. They lived outside Cottonwood near a bend in the Verde River, — "my river," Brannan says. The patch of green springs from Arizona dust about two hours north of Phoenix.

Brannan's home sat on a dirt road with no name. Visitors found it via cattle guard landmarks. Brannan and his brothers learned every inch of their river, swimming, hunting, fishing and trapping. He still knows the smell of creosote flowers after rain. He still knows his neighbor, who still lives in the trailer across the street.

As a child, Brannan watched his parents argue bitterly. He said one night, his dad tried to shoot out his mom’s tires as she drove away.

Alcohol and abuse drove his parents to a painful divorce, court records show. When he was about 10, his mother married a drug user. He pushed her around and threatened the kids. When Brannan intervened, he took a beating himself, a court record shows.

His mom kept them afloat with restaurant jobs. A few times she got behind and the power was shut off. Her boys wore Goodwill clothing, freshly ironed.

Brannan got his first job at 12, washing dishes at a restaurant called the Paragon. At 14, he drank until he blacked out and woke up injured. He smoked pot and later used cocaine and meth, court records show.

In high school, the blond, blue-eyed athlete lettered in football, tennis and golf. He helped with his family’s silk screen business. He struggled to attend all his classes, but he managed to graduate with honors.

At 17, he enrolled in an exchange program in Denmark. There, he said he played American football, ate well, did two cycles of anabolic steroids, came back jacked and found work as a personal trainer.

Brannan found a place under the wing of Dr. Thomas Peters, a wealthy orthopedic surgeon in Cottonwood who treated Brannan’s bad knees when he played high school sports. Peters eventually married Brannan’s mom.

His new stepdad represented security — Brannan didn’t have to worry about his mom going broke. He didn’t have to scrounge for a school application fee or worry that a surprise car repair would break him. He went into the operating room with Peters and considered programs to be a nurse or surgical tech.

“Why wouldn’t you want to be a surgeon?” he recalled Peters saying, nudging him to set his sights higher.

By age 19, Brannan had reconciled with his biological father, who had quit drinking. He stayed at his dad’s home in a Phoenix suburb and enrolled in a Mesa Community College pre-medical program, hoping to attend Arizona State University. His father saw him as bright and personable, he’d later write in a document filed in court.

But also “aggressive.”

Brannan suspected his girlfriend was with another man, a court record shows. He was said to be a “bad ass.” So Brannan put his dad’s loaded .38-caliber revolver in his pocket and drove to the home of Christopher Dempsey.

He saw his girlfriend’s car at Dempsey’s home. He wanted to “catch them in the act,” the court record shows.

Brannan repeatedly kicked the front door, trying to break it down.

Dempsey lunged at Brannan and punched him in the face. Brannan pulled the gun, hit Dempsey with it, and it fired near Dempsey’s head.

Brannan fled and when he was soon arrested, he heard over the police radio Dempsey was hurt, but the bullet had missed.

"Damn,” Brannan said, according to a report filed in court, “I should have shot him.”

The cops charged Brannan with aggravated assault, which could mean jail time.

He cleaned up for court. Well-groomed. Big aspirations. He presented “the image of the all-American boy next door.”

He gave $5,000 to Dempsey, who told the judge Brannan wasn’t the aggressor and “his actions were taken in self-defense in mutual combat.”

“He came to my house with a gun trying to break my door down and I kicked his ass,” Dempsey said in a text message to The Republic. “He knows it.”

Brannan’s father and stepfather wrote letters to the judge about his promising future. He pleaded guilty to a reduced charge of criminal damage. The judge gave him probation, which he completed by age 22.

Brannan enrolled at ASU and connected with other students charting a med school path. Next step: the Medical College Admission Test, or MCAT.

Brannan crunched hundreds of practice problems. But he had long grappled with feeling like an imposter.

“Every time I do something great, I feel like they're going to figure it out,” he said in an interview, “and I'm setting everybody up, and it's getting even worse, and every time I make progress all it does is raise everybody's hopes, so that when they see who I really am, then it's going to be a disaster.”

At the same time, the MCAT was an independent measure.

“You can't fool this,” Brannan thought. “No way that you can parlor-trick and personality your way through the MCAT.”

He killed it.

He got an acceptance letter to study medicine at the University of Arizona and wept in the post office.

“I’m such a fraud, and they let me in any way,” he thought. “I’m going to let them all down when they figure out who I am.”

Within a week, he was in handcuffs.

He’d gotten involved in a nationwide marijuana smuggling ring. It started with favors for his ASU roommate, he said. Like: Go buy boxes. And then: Hey, listen, can you weigh out 5 pounds and put it in a box? And later: Could you just drop that off? I’ll give you 200 bucks.

“I very knowingly contributed to my own downfall,” Brannan says now.

He remembers sitting outside the Scottsdale stash house. A police cruiser pulled up.

Pretty soon he was handcuffed, a black Yukon squealed around the corner and an agent leaped out, badge dangling from a chain: “DEA!”

They found 900 pounds of pot: 121 bricks topped with room deodorizers stacked under a bedroom window, five bales in the kitchen, seven bales in a storage room off the detached garage. A bale, Brannan explained, is 5 to 20 pounds of marijuana, flattened into a rectangle and rolled like hay in a field.

The cops also discovered steroids in Brannan’s car. Brannan, his one-time roommate, his girlfriend and another man were arrested.

He sobbed to his father: “My life is over, Dad.”

'Too good a deal'

As his case wound through court, Brannan went to study medicine at the University of Arizona. At orientation, he told the administration about his recent arrest.

“You guys need to know that this is not a case of wrong place, wrong time,” Brannan said. “I am not a babe in the woods. I knew what was going on. I knew that my roommate was trafficking marijuana or was selling marijuana and I knowingly committed acts in furtherance of his criminal activity.”

They were alarmed but let him stay. He had to see a psychiatrist and attend 12-step meetings.

“I first dismissed him as a misplaced musclehead,” one classmate later wrote.

Then Brannan rose to the top of his class.

In his third year of school, Brannan said he got an exceptional score on the first portion of a standardized test to be a licensed doctor. An idol, Dr. Harlan Stone, pulled him aside. “Scott, we need to formulate a plan for your surgical future.”

Finally, everything had come together. His value was independently verified. He felt unadulterated joy and accomplishment.

Then he went to court.

The assistant prosecutor on Brannan’s case wanted to hammer him.

But Brannan had the counsel of A. Melvin “Mel” McDonald, one of the most prominent attorneys in the state. Brannan said that through construction contacts, his mom put him in touch with McDonald, who was a former U.S. attorney, Maricopa County assistant prosecutor and superior court judge. Brannan said he recently finished paying McDonald’s fee in $1,000 monthly installments, which he figured total at least $50,000. They’re in touch to this day, Brannan said, close to best friends.

“He just totally went to work with hammer and tongs with the county attorney’s office,” Brannan said.

The judge declined to meet "informally" to discuss Brannan's case. But McDonald pulled off a deft maneuver, convincing the county’s highest-ranking prosecutor to overrule the assistant prosecutor working on Brannan’s case.

Brannan and his co-defendants got deals that drew skeptical comments from a judge handling a related case; the defendants were getting "too good a deal," the judge said, according to a court document.

Brannan pleaded guilty to attempted possession of more than 4 pounds of marijuana for sale and cooperated with the cops investigating the drug ring, which reached from Arizona to Massachusetts.

His plea exposed him to 8¾ years in prison.

The judge sentenced Brannon to 2½ years.

After the sentence, McDonald went to an old-school central Phoenix steakhouse called Beef Eaters, he said. He looked across the room and spotted Rose Mofford, a former governor who McDonald said had appointed the judge who sentenced Brannan. He walked over, sat down and told her how he was devastated that Brannan went to prison.

“Well, if I can ever help,” he recalled her saying. And the duo, along with state legislator Polly Rosenbaum, got to work.

At the prison in Florence, they called Brannan “Doc.”

As a white inmate, he caught the attention of the Aryan Brotherhood. They learned he had cooperated with police, and they fired a “torpedo” at him — an inmate seeking higher status within the gang. He clobbered Brannan with a lock tied to a sock. It hurt, but Brannan wasn’t hospitalized.

Brannan hunkered down for his prison term. Each day he woke up, put his feet on the floor, and prayed: “Please, God, please let me be a doctor.”

He tried to keep up with his medical studies and begged the guards to raise his allowance of seven books at once, seeking copies of “The Fountainhead,” “Siddhartha,” “Evolution of Desire” and “The Mating Mind.”

He complained repeatedly about prison conditions, but always in genteel terms:

"The recent changes in the menu have been met with widespread and extreme dissatisfaction, bordering on outright rage. Of this I am sure you are aware...”

While Brannan was lobbying for better cable reception and pest control, his lawyer convinced the state clemency board to change a policy to consider his case early.

“It didn’t hurt that I had been a superior court judge and U.S. attorney,” McDonald said.

Then he submitted a packet in support of Brannan’s clemency as thick as a phone book, which read like a who’s who of powerful Arizonans. In addition to Mofford, McDonald was able to secure the support of former Arizona governors Fife Symington, Evan Mecham and Raul Castro.

And the aspiring medical student leaned on an old family friend, Steve Twist, a former assistant state attorney general. Brannan said his father and Twist went to Camelback High School and served on student council together.

Twist wrote a letter calling for mercy for Brannan, provided to The Republic by Brannan’s attorney.

"As the primary author of the laws he broke, I would fully support such a decision,” Twist wrote.

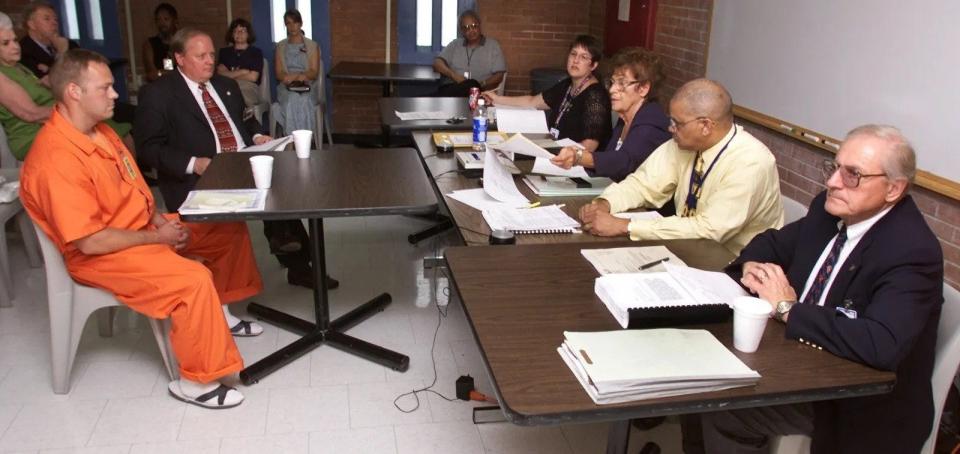

Brannan went before the clemency board wearing an orange jumpsuit, wrists shackled to a chain around his belly, connected to a chain around his ankles. He jangled into his hearing.

In the gallery, he saw his old mentor, Dr. Stone. He spoke on Brannan’s behalf, saying he had a bright future in medicine.

A few months later, guards put him in a pair of too-large, prison-made jeans, a chambray shirt with misaligned pockets and navy blue waffle shoes. They released him to his father.

The clemency board had heeded Brannan’s powerful chorus. Gov. Jane Hull signed off in October 2002, slashing an already sweet plea deal. Of the 572 cases considered by the board that year, Brannan was among 12 people – 2% – whose sentence was reduced by the governor, a Republic story shows.

His co-defendants served their full sentences.

A judge ordered Brannan to pay $102,000 in fines on his drug case.

Brannan estimated he earned $20,000 from the drug operation. Through his attorney, he successfully argued to reduce his fine from the proposed six figures to $14,000 — less than the proceeds of the crime.

Though he admitted to his participation, his attorney convinced a judge to dismiss his charge.

To this day, he’s haunted by his mugshot.

“You feel like you’re kind of walking a tightrope,” he said. “You want to reveal yourself to people, but then there’s some things that you hope they don’t know.”

Brannan was plucked from prison, but he couldn’t entirely get back on course.

Brannan was grilled before a committee at the University of Arizona but said he ultimately accepted a deal to part ways with the school, taking the credit for the school work he’d done up to that point.

He found it hard to transfer to another U.S. school, he said, so he looked abroad.

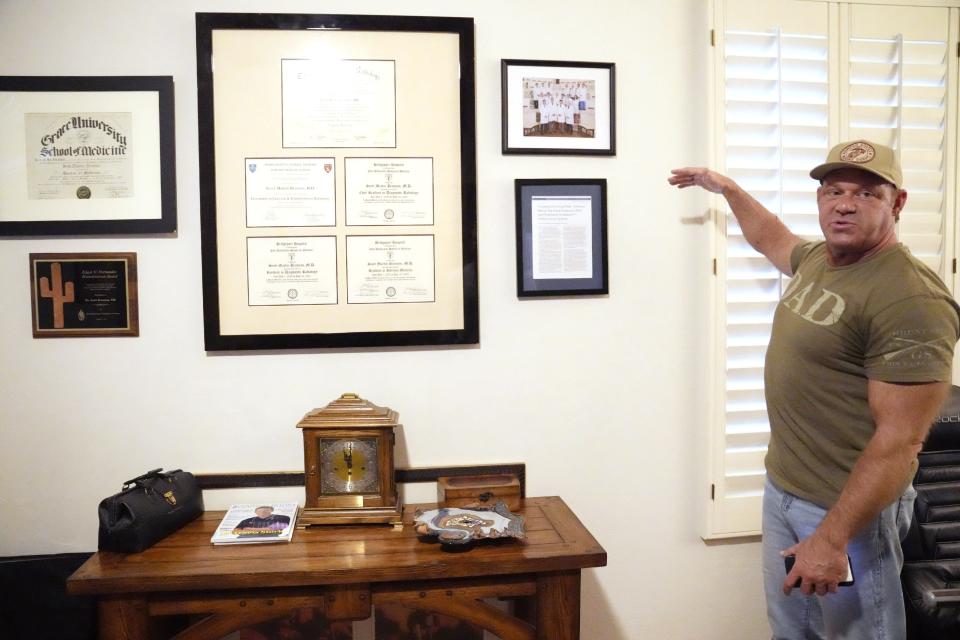

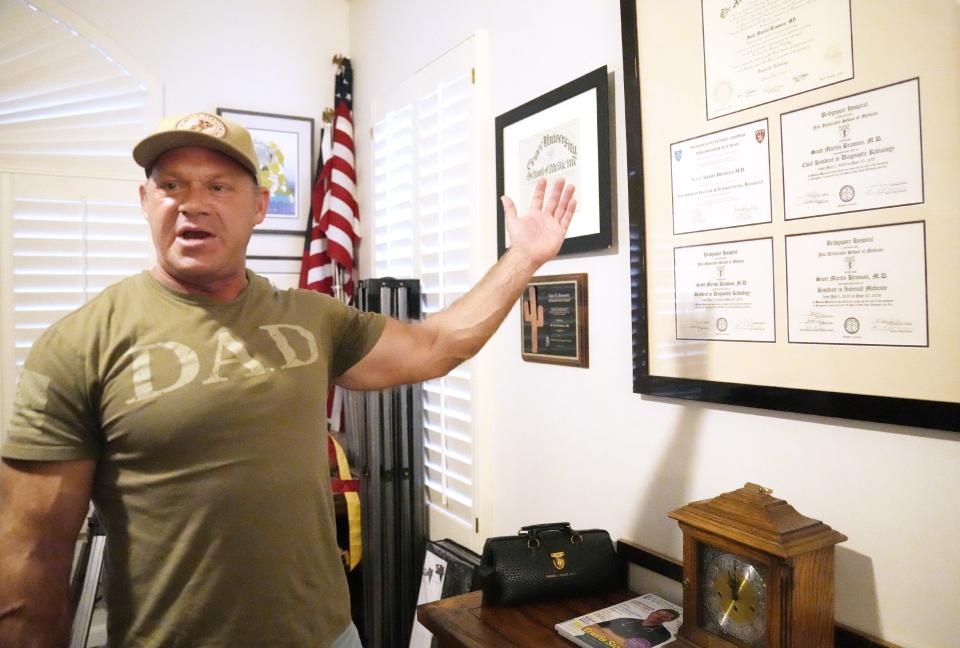

He was accepted by Grace School of Medicine in Belmopan, Belize.

Brannan said he’s never been to Belize. In the third and fourth years of his medical education, he was remotely enrolled at the school in Central America but spent his time rotating through U.S. hospitals.

The school ceased to exist in Belize on the exact day in 2004 Brannan claims as his graduation date. Brannan said the school didn’t want to pay a fee to continue operating in that country, and he had enough credits to graduate when the Belize campus closed. The government of Belize declined to comment.

Meanwhile, in Panama

A few years after Brannan found the school in Belize, the businessman who would launch Modern Vascular was moving money around in Panama.

Hailing from Soviet Ukraine, Yury Gampel is a chiropractor by training. He has ties to a sprawling home in the ritzy Los Angeles suburb of Calabasas, and a taste for the Amalfi Coast and George Michael. His empire included managing surgery centers, as well as stakes in RV parks and a rehab company once cut off from Medicaid following what an Arizona judge determined was a credible allegation of fraud.

Gampel and his wife sought the counsel of Mossack Fonseca, a law firm notorious for hiding money for the world’s rich and infamous, as revealed through the collection of millions of leaked documents known as the Panama Papers.

The documents were first shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and Süddeutsche Zeitung, and later with The Republic.

Gampel and his wife used Mossack Fonseca to create a company, the Panama Papers show. The company bought a condo in Trump Ocean Club International Hotel and Tower, a sail-shaped waterfront luxury tower in Panama City reportedly tied to money laundering. The law firm was reportedly closed and its namesake founders were among those charged with crimes; two members of Congress pressed the Trump Organization, which was controlled by Donald Trump, about the allegations of money laundering, a Reuters news report said.

Others who bought into that building included organized crime figures, NBC News reports show. There was David Murcia Guzman, who was convicted in the U.S. of laundering money for drug cartels. Then there was Louis Pargioias, who pleaded guilty in Miami to conspiracy to import cocaine. And then there was Stanislav Kavalenka, who was charged in Canada with procuring women for prostitution.

The Gampels’ contract, in which Yury Gampel’s name is crossed out and his wife’s is handwritten, guaranteed that for $571,500 their “de luxe'' 938-square-foot studio would come furnished and finished in marble and granite. They’d get valet service and, for an extra $15,000, access to the building’s beach club.

Ultimately, Gampel bought 10 condos in Trump Ocean Club, an email shows.

“To purchase real estate in Panama, a buyer needs a Panamanian-based entity established to purchase the real estate,” a spokesperson for Gampel wrote in an email. “In 2007, Mr. Gampel was an investor in a Panamanian corporation named Orio Management. The company purchased condo units at the Trump Ocean Club, which was being built in Panama City at the time. Mossack Fonseca served as the local registered agent for Orio Management and provided no other services. All appropriate and relevant disclosures were made in both the United States and Panama.”

It’s unclear what became of the investment, but Panama Papers records show Gampel’s company was “struck off,” with an “inactivation date” listed a couple years before he launched Modern Vascular.

Do you know about trouble at Modern Vascular? Here’s how to get in touch

Blessed by a Medicare billing code

On at least the several occasions that Brannan publicly described his education, he didn’t mention the defunct Belize med school.

“I was lucky enough to get educated at some great places back on the East Coast, at Yale University Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School,” he said in one radio interview.

His bio on the Modern Vascular website says that “he completed his education at Yale University, Bridgeport Hospital.”

His bio at a 2018 medical conference listed his credentials as “Residency: Yale University” and “Fellowship: Harvard Medical School, Vascular and Interventional Radiology.”

His file with the Arizona Medical Board says after graduating from the school in Belize, he went to “Yale University-Bridgeport Hospital Internal Medicine Residency” in Connecticut. Bridgeport Hospital is part of Yale New Haven Health System, but that’s separate from Yale University, according to university spokesperson Karen Peart. “Yale University Hospital” doesn’t exist.

Brannan did a fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital, including training as a clinical fellow at Harvard Medical School, according to the school’s spokesperson Laura DeCoste. But she wrote in an email it is not accurate for him to say he has a Harvard diploma.

“Please note that Dr. Brannan does NOT have a degree from Harvard Medical School, nor does he have any affiliation or association with the school,” the university wrote.

Brannan bristled when asked about the inconsistencies. He wrote in a text message that whoever wrote his bio at the 2018 medical conference “was obviously a layperson and it definitely wasn’t me.”

He wrote that he’d never entered Harvard Medical School.

“I have never misled anyone about my training,” he wrote. “I’m very proud of the education and training I received.”

Brannan married his second wife, Vera Assad Gebran, in 2005 in Lebanon, a few months after divorcing his first wife. Brannan and Gebran have four children.

Brannan would claim in his divorce from Gebran that despite his big income, she pressured him to earn more. Gebran would claim in court Brannan was abusive, used steroids, punched holes in a wall, kicked and shattered a mirrored bathroom drawer, threw her computer in a pool, urinated on her clothing, banged a child’s tennis racquet so hard it disintegrated, tore the playroom door from its hinges and slammed steel gates until they broke.

After Massachusetts, Brannan took a job in Missouri, where he was fired “due to too many consecutive patient complications and hostility in the workplace,” according to court documents filed by Gebran. He worked in Illinois, where he faced a lawsuit claiming he damaged a woman’s artery. Brannan said the case settled for about $100,000.

Illinois is also where he learned of a quirk of regulation that changed his career.

He was working on an idea to open arteries in an outpatient setting. Instead of working at a hospital, with big overhead and more oversight, he could probe blood vessels in a doctor’s office.

Brannan heard a rumor about an uncommon billing code for Medicare, he would later explain in a deposition filed in court.

He went to a library, got on a computer and looked it up.

Sure enough, in 2011, Medicare greatly increased the amount of money a doctor could bill for opening an artery in the leg with a billing code worth an average of about $12,000 per procedure done in an office setting.

“It's a very niche little code, 37229 code,” Brannan said under oath in a deposition, “... not very many people knew about it.”

The code underpinned a business idea he said he pitched to an Illinois clinic.

Brannan’s wife would later say in court he left Illinois after he was fired and came to Arizona to moonlight. But the way Brannan tells it, his practice was sold and he moved to Arizona’s Navajo Reservation in hopes of reducing amputations. A resume he provided shows several jobs during this time.

Thanks to work his mother did to help build health care facilities, she became chair of the Navajo Hopi Health Foundation, Brannan explained. His stepfather was chief of orthopedic surgery for Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation. When he was trying to get out of prison, Brannan pledged to serve vulnerable communities free of charge. For a while, he worked in Tuba City.

Brannan later joined Dr. Joel Rainwater, an interventional radiologist like Brannan with a practice based around Phoenix now called Comprehensive Integrated Care. Rainwater also ranked high in the country among similar doctors billing Medicare, but Brannan blew past him.

Brannan brought over his affinity for helping Native Americans, a group more vulnerable to diabetes than any other race, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He’d later describe forming relationships with patients including members of the Navajo Nation, the Colorado River Indian Tribes, San Carlos Apache, Gila River Indian Community, and Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community.

Diabetes is a precursor to the conditions Rainwater and Brannan treat, so it was a rich target, and Brannan grew that part of the business “exponentially.”

But soon there were problems.

His tax records show he was earning at least $300,000 annually during these years, but he and his wife owed more than $80,000 in unpaid taxes.

Within months of joining Rainwater’s shop, Brannan was suspended from a nearby hospital they were contracted with “due to excessive charting and documentation delinquencies,” Rainwater said in court.

Brannan disputed that, saying in an interview he’s never lost hospital privileges.

Hospital administration complained to Rainwater. Because Brannan didn’t dictate what he did for 28 cases, hundreds of thousands of dollars in charges had been held up, Rainwater wrote in an email later filed in court.

Some at the hospital were afraid to work with Brannan, Rainwater wrote in the same email. They said Brannan canceled their orders without communicating, was unreachable to discuss patient care and was abrupt with the staff.

“You are a fantastic physician with otherworldly skills,” Rainwater wrote. “l need you to fix these issues.”

Rainwater would claim in a lawsuit related to Brannan’s employment that Brannan used amphetamines and steroids and got too close to a competitor in town — Modern Vascular. A letter filed in the lawsuit, which has since been settled, says Brannan once left the premises after directing staff to sedate a patient.

Brannan accused Rainwater of "stealing all of the Native American patients for himself,” according to a court document filed in the case. Rainwater said the settlement involved neither party admitting fault. Brannan’s attorney said the terms of the settlement were confidential.

Brannan countersued, claiming Rainwater’s lawsuit made defamatory remarks about him. Brannan later dropped the lawsuit, court records show.

The final straw came in March 2017, when one of Brannan’s patients died.

“I had a complication with a patient,” Brannan later said in a deposition, “where she wound up losing a lot of blood during the case. We got her bleeding to stop. Sent her to the hospital for a transfusion. She was fine for two days. And then on the night of the second day, she wound up having a stroke and she died.”

Rainwater fired him.

“I – I had literally begged, begged,” Brannan said, “I’ll do anything. Please, just let me – just let me work. I have to work.”

Enticing doctors to invest

At a restaurant in Woodland Hills, a fancy Los Angeles suburb, the profitable idea that became Modern Vascular was born, according to the account of one man who says in a lawsuit he was involved.

Vladimir Zeetser says he and Yury Gampel later fleshed out details at a dinner in Encino. Then Gampel ran off with the idea, Zeetser claims. Gampel denies doing so; the suit is ongoing.

“I’ve had no involvement in that company since basically early 2018, in terms of any decision making,” Zeetser said. “I’m very disappointed in what he’s turned that company into.”

Zeetser had run vascular centers in California. He says in his lawsuit that he and Gampel agreed to pool their experience and connections to build centers in Arizona and then across the country. They’d share ownership and give 25% to doctors who invested with them.

That last part is important.

Modern Vascular needs patients to stay in business, as clinics generally do.

They marketed themselves. Brannan spoke on the radio, representatives appeared on local news channels and the company took out full-page ads in The Republic.

It’s illegal to pay doctors for referrals — that’s known as a kickback.

But Modern Vascular exploited a loophole: It engaged some referring doctors as investors. On paper, those doctors weren't getting paid for sending patients, they were getting dividends based on the success of the business they own a piece of.

"It just was a perfect marriage for a lot of podiatrists, like shoot, why wouldn't we want to invest in something that's good for our patients, but also on the back end kind of get a little somethin’ somethin’,” said podiatrist Randall Brower, who was among the earliest investors. He said what he did was ethical.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (which oversees Medicare) and the DOJ declined to tell a reporter whether Modern Vascular’s arrangement with investors is legal. The DOJ's December complaint claims the company made illegal payments to prompt doctors to send them patients.

Some health care business arrangements that would induce referrals can be protected from kickback prosecution under “safe harbor” regulations, according to a spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General. It’s unclear whether Modern Vascular has that protection because the office wouldn’t confirm or deny whether it qualifies for safe harbor.

The company’s founder referred a reporter’s questions to a PR firm whose specialties include “crisis communications.” Its representative, Tanner Kaufman, wouldn’t say whether Modern Vascular is operating within a safe harbor agreement.

“To be clear, the simple fact of physician investment in another medical practice is not problematic or against the law,” Kaufman wrote in an email.

Brower practiced podiatry for 18 years. Prior to Modern Vascular, he said, he didn’t have a good place to send his patients to get vascular care for the narrowest reaches of the legs.

He attended a pitch at the Modern Vascular office in Glendale, where Gampel and Brannan expounded on the benefits of the technology they were using — and the riches the investors could expect. Their hope was that in a few years, they’d sell the company and make a fortune, Brower said.

He paid $7,500 for 400 shares, according to a contract he shared with The Republic. Modern Vascular sold shares in two flavors: the kind Brower bought could be purchased only by doctors. The doctor investors could be kicked out of the company, the contract shows, but other investors couldn’t.

When a podiatrist in Mesa stopped sending patients to Modern Vascular because he felt they were getting poor care, Gampel “terminated” his stake in Modern Vascular and “forcibly” bought back his shares, according to claims in one of the lawsuits joined by the Department of Justice.

Brower said he referred 20 patients a month to Modern Vascular and made his money back in three months. He estimated he ultimately made $100,000 on his $7,500 investment.

Brower said he felt his patients were getting good care. But he also felt pressure from Gampel to refer more.

He recalled investor calls in which Gampel would review referral numbers and point out that if the investing doctors wanted Modern Vascular to do well, they needed to send more patients.

“That was why they wanted podiatrists invested, because just by being invested naturally will push you to utilize the service,” Brower said.

The pressure for referrals also came down on the rank and file of Modern Vascular. The company’s marketing representatives were tasked with encouraging referrals, and they were aware of which doctors were investors, according to Kenneth “Chip” Macdonald, a former Modern Vascular marketing executive now being sued by the company on the claim he tried to poach employees after he left.

“The experience was the worst that I’ve ever experienced in my career,” he said.

Macdonald said he was visited at home and asked about Modern Vascular by special agents from the FBI and the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General.

One of the lawsuits joined by the DOJ said Modern Vascular pursued unnecessary procedures for four patients referred by investor doctors. It said Gampel bragged to investors that Modern Vascular was so successful he was able to buy a Ferrari.

Two of the lawsuits joined by the DOJ allege violations of the Stark Law, which bans doctors from sending people to a publicly funded clinic in which they have a stake, unless an exception applies.

Responding to a reporter's questions about Modern Vascular, the PR representative wrote: “These laws and regulations do not apply to our business.”

When addressing investing doctors at least a year ago, Modern Vascular said it would change its corporate structure to “lower certain health care legal risks” and “be Stark compliant, which will allow us to capture income streams associated with designated health services currently unavailable due to Stark law requirements,” according to a Q&A document that was shared with The Republic.

Modern Vascular reorganized so that investing doctors were in business with a single nationwide management company, rather than getting dividends from the local clinic to which they were sending patients.

"It is a workaround of the Stark Law,” said Dr. Marty Makary, public health researcher and professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “If it doesn't violate the letter of the Stark Law, it certainly violates the spirit of the Stark Law."

The Arizona Department of Health Services received a complaint more than two years ago that said Modern Vascular was paying referring doctors, a document from the agency shows. The document shows regulators determined they had “no jurisdiction over billing fraud procedures” and they should refer the issue to the state attorney general and medical board. Those offices didn’t respond to a request for further information.

Brower lost faith after Modern Vascular missed payments to investors, he said. He shared emails in which he questioned Modern Vascular management about the missed payments, and a fellow podiatrist said the company hadn’t paid dividends in months. In the emails, the company said it was reverting to quarterly payments rather than monthly because it was making changes to its accounting methods.

After going unpaid for about nine months, Brower pulled his money.

He now refers patients elsewhere.

Looking back, Brower realized Modern Vascular operated on his patients at a much higher rate than the new group he uses.

“That was very obvious to me after I left,” he said.

Hungry for patients

Dr. Patrick Duffy’s office was sparse. In his ninth week on the job at Modern Vascular’s location in Surprise, Arizona, his gray bookcase was mostly empty, and his gray walls were bare.

Gray carpet. Gray desk. Gray scrubs.

Neon green sticky notes.

Duffy jotted down the names and numbers of doctors he wanted to court as potential sources of patient referrals. He said he planned to write them letters.

“When you go to doctors and you're trying to gain their trust, whatever, you just want to say: I can be a resource for you,” Duffy said in an interview in June. “Because that's what referring physicians need.”

Duffy came to Modern Vascular from a hospital in Houston, and he has a clean file with the Arizona Medical Board. He declined to say what he’s paid now but said he took a 20% cut to his base salary to join Modern Vascular. He described having greater autonomy and better work-life balance.

He allowed a reporter to watch him practice his craft.

The operating room was chilly. Smash Mouth’s cover of “I’m a Believer'' complemented the hum of machines.

Just for fun the staff gave celebrity names to the tools of their trade. Tim McGraw, the Rotablator, could grind up blockages.

A patient lay under blue sheets, hooked to an IV. A little blood dripped on the floor. That’s normal, Duffy said.

Everyone wore lead aprons and throat coverings, because the procedure involved using an X-ray so the doctor could watch a pulsing gray image of the patient’s right femoral artery — the big one that runs down the leg — as a wire was fed through.

Duffy said the previous week he worked 60-65 hours and did 11 surgeries. He denied pressure from management to pump up the numbers.

But he said he gets a bonus based on the number of procedures he does. It’s a common practice, he said, but it could encourage a doctor to do a lot of procedures.

“I think if you're the wrong type of person,” Duffy said, “it could.”

Lawsuits filed on behalf of 12 Modern Vascular patients say they were wronged.

Nina Robertson, 88, sought care from a Modern Vascular clinic in Albuquerque.

The medical team ruptured one of Robertson’s arteries, she says in an ongoing lawsuit, and she was taken to a hospital with a basketball-size blood clot in her belly. Modern Vascular disputes the claim.

“I was lucky, I got out of there alive, barely,” she said. “Maybe some didn’t.”

She’s right.

At least two people died following procedures by Modern Vascular, according to lawsuit claims. The family of Sally Hendrix says she died on the operating table from a heart attack caused by a Modern Vascular surgery she did not need.

“Modern Vascular, LLC has a standing policy or practice to routinely schedule patients for unnecessary angiograms and/or interventional procedures on patients’ lower extremities as a matter of course, regardless of medical necessity, for maximum financial benefit and without due regard for the safety and welfare of patients like Ms. Hendrix,” the family's lawsuit says. Modern Vascular denied fault in court and the lawsuit is ongoing.

Kae Barnes sued Brannan and another Modern Vascular doctor, claiming they failed to attempt conservative treatments prior to operating on her, saying they destroyed blood vessels, leading to the amputation of her left leg.

“At the end of the procedure when Defendant Brannan was closing (Barnes) up, she felt a sharp and overbearing pain in her ankle,” her lawsuit said. “(Barnes) yelled out to alert Defendant Brannan to check her ankle, where he found a wire remaining. The wire ran from (Barnes’) upper leg to her ankle. Defendant Brannan removed the wire, closed her up, and immediately left the room without saying a word.”

Modern Vascular has challenged Barnes’ claims in court.

Beyond the cases described in lawsuits, police and EMS records show more Modern Vascular patients in trouble. Medics responding to the Modern Vascular clinic in Tucson found a patient lying on an exam table after a procedure.

The doctor at the scene told the medics that the patient was “bleeding out internally.” The patient lost 3 liters of blood, roughly half the blood in an average adult.

Dr. Jack Hannalah, named in the emergency response report, didn’t respond to a reporter’s calls and emails seeking comment.

A staff member clutched the incision on the patient's right upper thigh. The woman was unresponsive and cold. Medics loaded her up and drove her to a hospital, with Hannalah riding along.

The record doesn’t include her name or say whether she survived.

More problems, more money

A man carrying papers approached Brannan’s Scottsdale home. There was no answer at the door, blinds closed, quiet. But the garage door was up, the light was on, a minivan was parked inside with the door open.

Brannan texted his wife, court records show: “I know that this is a weird question, but are you having me served with something?”

It was a divorce, adding to Brannan’s rough year in 2017. He ultimately earned at least $196,000. But he moved eight times that year and he was evicted from one home for failing to pay rent, Gebran said. He later denied that claim in an arbitration proceeding in the divorce.

As the turmoil in Brannan’s personal life increased, he found ways to grow his income.

He worked part time with Modern Vascular starting about July 2017 at the company’s original location in Mesa. Soon after, the Arizona Medical Board hit him with an advisory letter for puncturing a patient’s artery and “inadequate documentation.”

His divorce grew contentious, with allegations of abuse and drug use. Brannan was investigated by Mesa police after his wife found nude photos of their children on a phone. The police determined those didn’t qualify as child pornography, but they did find “numerous images and videos” of adult pornography, according to a police report.

Despite the personal trouble, his earnings increased, topping $450,000 in 2018. His wife claimed in their divorce his income was even higher.

Modern Vascular spread across the country, seeking out concentrations of elderly people who might be more prone to the disease they treat. Four locations ringing Phoenix and one in Tucson. Four in Texas. And one location each in Albuquerque, Denver, Indianapolis, near Kansas City, Kansas; Mississippi; and St. Louis.

Along the way, the company focused on numbers. An email shared with The Republic shows their founder and former CEO pressing doctors about how many procedures they had scheduled in a week.

“Are there 7 procedures this week?” Gampel wrote. “We showed 17 at beginning of week.”

Another Modern Vascular executive circulated an email to doctors across the company describing how to work billing codes to pump up revenue.

“This increases reimbursement almost 2K at least per case,” the email read.

Management pressed its staff on performance metrics, questioning when a clinic didn’t hit a target number of procedures in a week, according to a clinical director education guide provided by a former employee. The document shows a clinic was pressured to do procedures on half the people who came in for a consultation.

It’s hard to say how well this paid off. Modern Vascular is a private company and records of its revenue are hard to come by. When a Modern Vascular executive hosted a Republic reporter at an office in Glendale this summer, it was empty. The executive said their team was working elsewhere.

When opening the clinic in Mississippi in 2019, the company filed projected financials for that location, which ended up attached to Brannan’s divorce. Modern Vascular estimated the clinic would do 254 outpatient visits and 364 procedures in the first year, charging $14,725 per procedure, earning roughly a 17% profit margin.

In 2020, Brannan was reimbursed more than $5.5 million for 6,236 services related to vascular interventions for his 286 patients, Medicare data showed. Ranked by billing, Brannan was joined by another Modern Vascular doctor in the top 10, with two others joining in the top 50.

Analyzed another way, Medicare data showed Brannan and three other Modern Vascular doctors ranked in the top 12 by how much they bill per patient.

“This is definitely an outlier,” Dr. David Armstrong, a podiatrist and professor of surgery at the University of Southern California, said of the high ranking cluster of Modern Vascular doctors.

Asked about his high rank, Brannan said he tends to do multiple procedures on a patient at once while other doctors might have patients come back another time. One of the lawsuits joined by the Department of Justice claims Modern Vascular tried to “maximize the amount of revenue per patient.”

A spokesperson for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services declined to comment on The Republic’s analysis, but confirmed it’s not possible to judge from available Medicare data the quality of their work or whether it was medically necessary.

Brannan also became a top doctor using products of one representative from Boston Scientific, a medical device company that generated nearly $12 billion in revenues in 2021.

Some symbiosis between device companies and surgeons is part of American health care. Boston Scientific makes wires, balloons and stents that doctors like Brannan use to open arteries. The development of smaller devices by companies like Boston Scientific in consultation with doctors like Brannan enables the procedures Modern Vascular touts as groundbreaking.

An Arizona representative of Boston Scientific said in a 2020 deposition filed in Brannan’s divorce that Modern Vascular got a rebate at a rate of 13% for the product they used. He said his company expected Modern Vascular to use Boston Scientific products 80% of the time. He estimated that rebate worked out to $250,000 each quarter in 2019.

The representative, Josh Thomas, said he didn’t know how much of that, if any, went to Brannan.

Brannan grew especially close with Thomas. Their kids played on the same football team. They went to birthday parties for each other’s children.

Brannan was once arrested at work on a low-level warrant for failing to appear in court to answer for a citation of driving with a suspended license and no proof of insurance.

Thomas bailed him out, according to a police report.

Thomas was also named as a Boston Scientific manager who “turned a blind eye” to internal memos saying Modern Vascular doctors were doing unnecessary invasive procedures with Boston Scientific equipment, according to a claim in one of the lawsuits joined by the DOJ in September.

The lawsuit states that sales representatives of the medical device juggernaut watched Modern Vascular doctors run dye tests that showed the arteries of patients were clear, but Modern Vascular doctors scheduled surgeries anyway. When sales reps complained to Thomas and higher-level executives, they were ignored, the lawsuit says, because Boston Scientific executives didn’t want to interrupt the company’s lucrative sales.

“We strongly disagree with the unsubstantiated allegations outlined in this filing, as we conducted an investigation when concerns were raised and believe that no inappropriate conduct by Boston Scientific or its employees had taken place,” company spokesperson Blake Rouhani said in an email. The company refused to elaborate on what the investigation found. A company representative said Thomas was still employed by Boston Scientific. His attorney declined to answer questions but said in an email that “Mr. Thomas’s conduct with respect to Dr. Brannan and Modern Vascular was professional and appropriate.”

The DOJ declined to go after Brannnan directly in that lawsuit. But he was scrutinized by the Arizona Medical Board, which in a 2020 advisory letter scolded his “failure to offer appropriate, established treatment alternatives to patients as their conditions worsened despite the performance of multiple endovascular procedures.”

Brannan fired back: “I feel the Board is unfairly biased against below-the-knee vascular procedures and issued this letter in its bias.”

In August, Brannan sat before the Arizona Medical Board for two hours to answer for eight potential violations. The board grilled him about using Ambien and prescribing drugs for his wife without keeping records.

They asked him about using steroids. He said he was prescribed testosterone and he bought a “prohormone” called “trenabol” off eBay. He had read on online forums this would improve fat loss and increase energy and strength. He said he presumed this supplement metabolized into a substance that prompted him to fail a test for a steroid.

He said in an interview he stopped taking Trenabol but still takes other supplements, as long as they’re not illegal.

“There's stuff that says, you know, it's going to have an effect similar to testosterone. And, you know, some people are stupid enough to believe that,” Brannan said. ”I happen to be one of those people who's stupid enough to believe that and keep my fingers crossed, hope that it's true.”

The board asked him about his patient who died in 2017.

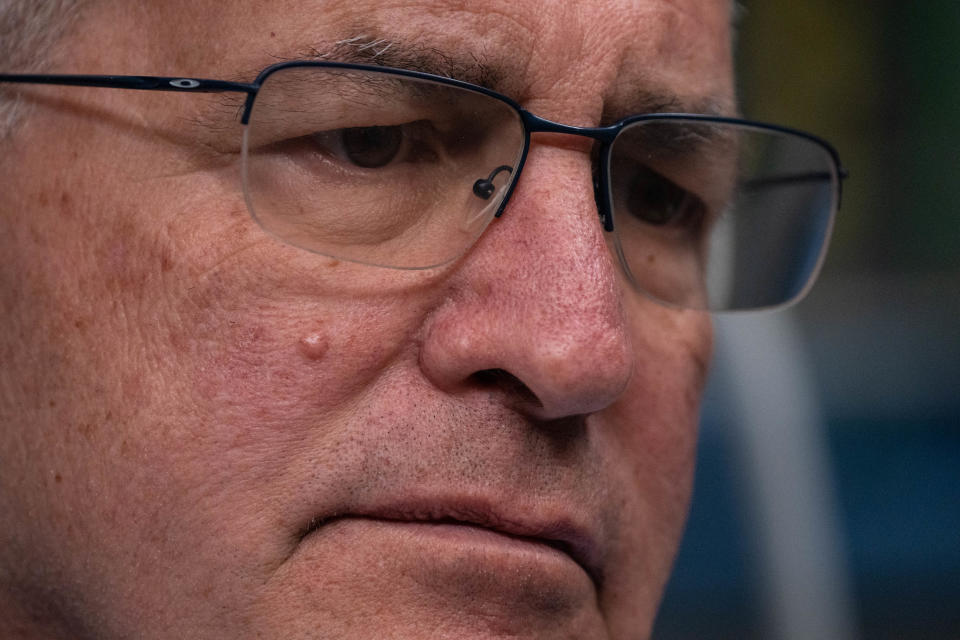

Claude DesChamps, internal medical consultant for the Arizona Medical Board, gave his thoughts before board members took their vote.

“In Dr. Brannan’s zeal to successfully restore arterial flow, he ignored signs of deterioration that should have prompted him to initiate transfer of care to a hospital sooner,” DesChamps said at the hearing. He said the patient died from blood loss.

As Brannan has done before, he calmly stood his ground, joined by an attorney, and tried to explain himself.

“I think I've improved things over time,” he told the board. “And I just have to take accountability for the documentation, and for the concern about my Ambien use and that's resolved.”

The board voted to censure him, compelling him to do a year of probation and get substance abuse treatment. The order would become final if approved at a board meeting in October. That’s one step short of losing his license.

He is free to keep practicing.

'If you run a pizza joint ...'

The spread of Modern Vascular clinics across the country has continued. The company opened a clinic in Memphis, Tennessee, in February. Another recently opened in Louisville, Kentucky.

Former employees of Modern Vascular and other doctors in the community expressed fear of retaliation for speaking out against the company. In addition to the lawsuit against Macdonald, the former Modern Vascular marketing executive filed by the chain’s management company, Modern Vascular sued a clinic with a similar name and Searchlight New Mexico, which wrote about Modern Vascular’s lawsuits.

An internal email shared with The Republic shows Chief Medical Officer Dr. Steve Berkowitz tried to do damage control following the New Mexico story, which said Modern Vascular “pushes unnecessary treatments and puts profits above patients.”

“We have some terrific opportunities here for story redirection, positive PR, and improved street credibility!” Berkowitz wrote, recommending that Modern Vascular “redirect the narrative to … reducing unnecessary amputations.”

When Berkowitz heard a Republic reporter was contacting former employees, he reached out and hosted the reporter and photographer for a tour of the Glendale clinic in April.

In a chilly operating room, he offered a spirited defense of the business.

He confirmed Modern Vascular was the subject of a DOJ “inquiry.” He wouldn’t talk about the company’s investors. He said the company has a target number of procedures for each clinic — the Glendale clinic's was 15 a week. And yes, that number does weigh on a doctor’s decision of whether to perform surgery.

“To say it doesn't is not completely true, because we need to have a business,” he said.

He summed up the approach in practical terms.

“If you run a pizza joint and you're not selling enough pizzas, you're not going to stay in business,” Berkowitz said.

One weekday, Brannan said he was scheduled to do six cases and had just worked a couple of 14-hour days. He says long days are never a problem. In a deposition, he said he might do 1,000 procedures a year.

“I don't know if he sleeps,” said Berkowitz. “I mean, this is what he loves. He doesn't turn down a case.”

As a used car salesman, Mike Bonebrake understands well the hunger for numbers.

But that’s no comfort.

For 30 years, Bonebrake made good money and supported his wife, daughter and granddaughter. He said he was a sponsored semiprofessional bass fisherman, he learned to fly a plane and, at 6-foot-2, he loved playing basketball.

Now Bonebrake, 60, said he can’t reach the top of his refrigerator.

Bonebrake had an ingrown toenail that wouldn’t heal. He went to a primary care doctor’s office, where a physician assistant couldn’t feel a strong pulse in his foot and wanted him to get that checked out.

She referred him to Modern Vascular. Their records on Bonebrake say he had risk factors: He had previously had a stroke and a heart attack, and he used to smoke.

Dr. Marc Eckhauser worked on his left leg. The PR firm representing Modern Vascular declined to comment on his behalf.

Bonebrake said his foot swelled to nearly double its usual size. It hurt. He went back to Modern Vascular, and they told him it looked better.

At a follow-up appointment a week later, his foot was still swollen and painful, leaving him unable to walk. The Modern Vascular doctor conceded it would need to be amputated. Siegrist, the surgeon who did Bonebrake’s amputation, told The Republic that Bonebrake didn’t need the original procedure Modern Vascular performed, a claim echoed in lawsuits filed on behalf of other patients.

Bonebrake spent a whole day figuring out how to lift himself up to a walker and get to the bathroom, he said. What might be nine steps feels like a 9-mile run.

“You know, just knowing what they do really makes me upset,” he said. “And it makes me mad, you know, it makes me mad. It makes me want to fight these people.”

As he sat on the edge of his bed where he spends most of his days, his wife walked in, holding a bill.

Modern Vascular wanted $372.94.

Investigative reporter Andrew Ford needs your help exposing wrongdoing. Reach him at aford@arizonarepublic.com

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Arizona medical chain chased profits, is accused of harming patients