Modesto man was found with blood on his hands. Why he can no longer be prosecuted for murder

In February 2019, Wayne Ferriera was found dead in his east Modesto home. The 72-year-old had been beaten and suffocated and numbers had been scrawled on his body in blue ink. His son Bryan was there, too. He had blood on his hands and a history of violence, including a recent assault against his father.

It’s some of the evidence that could have been presented against Bryan Ferriera if his case had gone to trial.

But for the second time, prosecutors had to drop the murder charges against Ferriera earlier this year and can never again charge him with his father’s murder. Doctors determined that attempts to restore Ferriera to competence were unsuccessful.

Ferriera, 51, is currently in a locked mental health facility but, given the history of his case, it’s unlikely he will be there for very long. Certainly not 15 years to life, the sentence for second-degree murder Ferriera was charged with.

“It (shouldn’t) matter if you’re competent or incompetent, if you kill someone you gotta do your time, especially if you are not mentally there,” said Bryan’s sister and Wayne’s daughter, Darlene Reyes. “That is the biggest reason you should be in a locked facility so you don’t hurt yourself and anyone else.”

For a defendant to be competent to stand trial, he must understand the nature of the charges against him and be able to assist in his own defense. Ferriera’s competence was called into question soon after he was charged.

Both at a state hospital and in a jail-based program, efforts were made to restore Ferriera to competence. But mental health officials concluded there was no substantial likelihood that he would regain mental competence in the foreseeable future.

It doesn’t matter that he could become competent at some point years from now. State law only allows a maximum of two years of efforts to restore a defendant to competence.

Sometimes if a defendant can’t be restored, the DA’s office will request that the County Counsel’s Office and the Office of the Public Guardian initiate a conservatorship proceeding.

Last year, 15 defendants, including Ferriera, were referred to the county offices, according to data from the Public Guardian.

The DA dropped the murder charge against Ferriera so he could be transferred to a secure mental health facility while he was evaluated for two types of conservatorships. One required a finding that he was a danger to himself or others and the other a finding that he is gravely disabled and unable to provide his own basic needs.

But a doctor decided he didn’t meet the requirements for either and Ferriera was released to a non-secured group home. He wasn’t even there a day before he was re-arrested last October.

“We kept tabs on him and based on our investigation it appeared that he had returned to competency and was able to understand the charges and assist his attorney and that is why we refiled,” said Chief Deputy District Attorney Wendell Emerson. But “during those proceedings (about nine months) doctors found he fell back into incompetence.”

Charges against Ferriera were dropped for good in June and the DA’s office again asked that he be considered for a conservatorship.

This time, a conservatorship was granted on the grounds that Ferriera is gravely disabled as a result of a mental disease; unable to provide for his basic personal needs for food, clothing or shelter; and unwilling to accept assistance voluntarily.

He is being housed in a secure mental health facility in the Bay Area, Reyes said, but she doesn’t think it will last long. The conservatorship must be renewed every year. Reyes said officials from the Public Guardian’s Office, which oversees Ferriera’s care, told her he is doing well in the facility and taking his medication. He could very well be released to a group home like he was briefly last year, regardless of whether the conservatorship is renewed.

The type of conservatorship Ferriera is on “requires the least restrictive placement based on the totality of the circumstances,” said his attorney, Chief Deputy Public Defender Reed A. Wagner. “In some cases that’s a group home, in others it is a locked facility, or anywhere in between.”

“A tragic limbo”

Doubts about a defendant’s competence to stand trial arise in hundreds of cases in Stanislaus County each year but the majority are found competent or are eventually restored to competence.

From January 2017 to September 2018 — the most recent years for which the DA’s office had data — 75% of the 881 defendants whose attorneys requested evaluations were found competent to stand trial. Of the defendants whose cases had to be dismissed, 117 were charged with felonies and 99 with misdemeanors.

But for this to happen in a murder case is extremely rare. None of the attorneys interviewed for this story could recall it happening in Stanislaus County in recent memory.

“I can’t recall a murder case where we were forced to dismiss the case as a result of the defendant being unable to be restored,” said Emerson, who has worked at the District Attorney’s Office for 22 years.

Wagner also couldn’t recall another case like this.

“This case is a tragedy because it is an example of how the criminal justice system is simply not set up to handle the mental health crises that are on the docket on a daily basis,” he said. “The criminal court systems are concerned with guilt and innocence, and frequently the feelings of the families of defendants and victims are waylaid in the interest of making those determinations. Here, with Mr. Ferriera not being competent to stand trial, the process abruptly ends, leaving both Mr. Ferriera and the victim’s family in a tragic limbo.”

Reyes said her father Wayne’s desire for Bryan was that he not become one of the hundreds of mentally ill people who are homeless in Stanislaus County. It was the reason he let Bryan continue to live with him despite illicit drug use and repeated violent outbursts.

While Bryan Ferriera remains in a locked facility, Reyes said she “feels at peace” knowing he is getting the treatment he needs and their father’s wishes are being fulfilled.

But she fears for the safety of her family and for the general public if he is released to a non-secure group home.

Ferriera is diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder, as well as severe cannabis, amphetamine and cocaine use disorders.

When he is on his medication and off illicit drugs, he can be kind and smart, Reyes said. But she has no doubt that if he is released to a group home, he will start using street drugs again, like he was at the time of Wayne Ferriera’s death.

“Death changes everything, time changes nothing”

Reyes acknowledges her brother’s mental health diagnoses but she also saw how he manipulated their father and believes he has been malingering. She said no doctor ever asked for her input or to provide history or context about her brother’s mental health.

Wayne Ferriera’s granddaughters wanted to see their uncle convicted and sent to prison.

“They feel that they got robbed of telling Bryan what they felt to his face,” Reyes said.

Her oldest daughter Monica Lopez wrote a victim impact statement about three months after her grandfather was killed and added passages to it in the following years.

Victim impact statements are typically read in court before a defendant is sentenced. Lopez will never have that opportunity but she read her statement to The Bee.

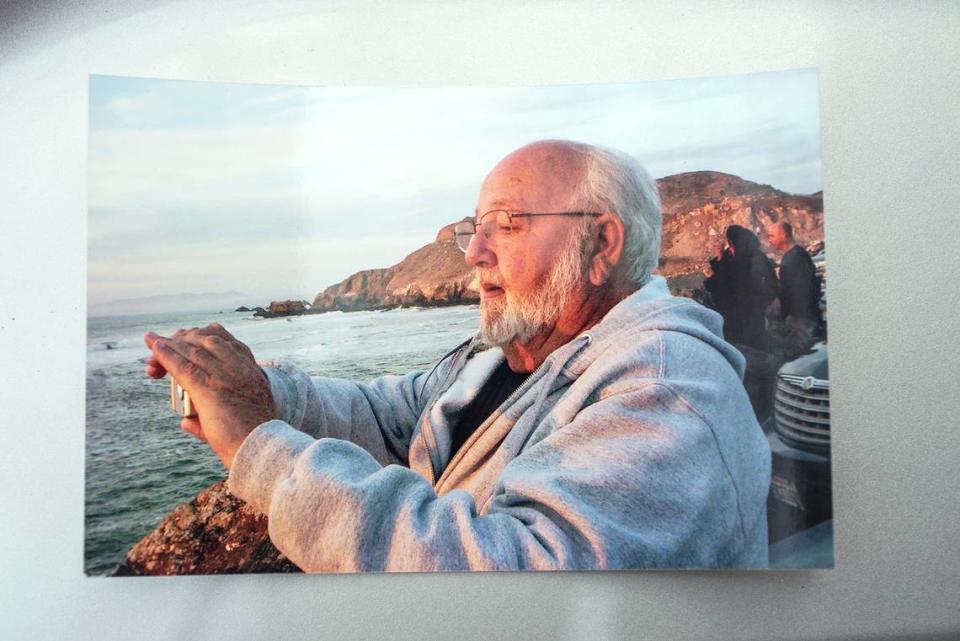

Lopez said Wayne Ferriera, whom she referred to as grampz with a Z, was her hero and a blessing.

Before he moved to Modesto from Ohio, Wayne Ferriera would take his granddaughters on trips to Toys R Us during his visits. “He told us, ‘fill up the cart,’” Lopez said, “I felt like I was the luckiest kid in the world.”

When she wants to feel close to her grandfather, Lopez looks up at the sky and talks to him.

“Death changes everything, time changes nothing,” she said. “I still miss your voice ... and just being in your presence I miss that daily. I miss you so much, the same as I did the day you died.”