After mom dies in KC police chase, kids get $3,571 each. How MO makes it hard to sue

In March 2022, a taxi driver being treated in an emergency room told a Kansas City police detective what he remembered from the crash that sent him there.

He had been driving a passenger just east of the 18th and Vine historic district when he saw a car coming at them “very fast,” he said.

That was just before it hit his taxi. Moments later, he looked in the back seat. His passenger wasn’t there anymore.

Then he saw her lying on the street, far away — she had been thrown more than 50 feet. An officer at the scene told him she was in a coma.

Now, at the hospital, the driver asked the detective: “Did she wake up?”

Erika Miller, a 38-year-old mother of seven, would not wake up.

She was one of two people killed that year in crashes resulting from Kansas City police chases.

The reason for the chase: The other vehicle was suspected to have been stolen in a carjacking six days earlier.

In other cases, cities have paid millions of dollars to settle lawsuits filed by the families of innocent people killed in police chase crashes. But that’s not likely to happen for Miller’s children, according to Brett Burmeister, an attorney representing the family.

Her kids will likely end up splitting $25,000 from the taxi company’s insurance and receive nothing more, he said. That’s $3,571 apiece.

Burmeister, who has won multi-million dollar settlements against law enforcement agencies in other chase cases, said he won’t be filing a lawsuit on behalf of the family. He and two other attorneys reviewed the facts and came to the conclusion that they would not have a strong case against the Kansas City Police Department.

They cannot point to a policy police violated in the chase. And the officers were far enough from the fleeing driver that they were not “in direct hot pursuit,” an important factor in how the courts would treat the family’s claims.

It’s one example of how Missouri courts shield police involved in dangerous pursuits from accountability, even when uninvolved motorists are severely injured or killed, according to several attorneys practicing in the Kansas City area.

“The decisions issued by Missouri’s appellate courts make it nearly impossible for an innocent bystander who is struck by a fleeing driver to seek compensation from the law enforcement agency that initiated the pursuit,” Burmeister said.

It’s a danger motorists are exposed to in the Kansas City area every day.

Dozens of police chase crashes in Kansas City

A monthslong investigation by The Star found that in two recent years, nine people have died after police chases in the metro including in Independence, Kansas City, Missouri, and Kansas City, Kansas. Eight of them were innocent bystanders.

Police across the metro engaged in more than 1,200 car chases in 2022. Those resulted in more than 150 crashes, 51 injuries and two deaths. Both deaths were related to Kansas City police chases.

Kansas City police alone, over the past five years, recorded 597 chases. Forty-one percent of them ended in collisions.

A total of eight people were killed in those wrecks. Five of them were innocent bystanders, including a 38-year-old woman whose 2-year-old daughter was injured in the crash, a man who had gone out to get ice cream for his girlfriend and her four children, and Ronald Campbell, the second victim from 2022.

The 44-year-old man, who was homeless, was sitting in a median when he was struck and killed by a vehicle that Kansas City police initially spotted because it had been reported stolen.

His father, Ronald Campbell Sr., said he thought police could have gotten a license plate number and then followed the driver at a safer distance.

“Too often, whether it’s someone dying or not, there’s civilians that get hurt in these chases,” Ronald Campbell Sr. said.

In that five-year time span, another 35 people were injured, according to a review of news stories from those years. Of those, six were suspects while the rest were passengers in suspect vehicles or uninvolved bystanders.

Two more people, an innocent bystander and a suspect, were killed last month.

Mayor hopes for new look at chases

Mayor Quinton Lucas, who has a seat on the Kansas City Board of Police Commissioners, said he hopes that the department looks at “a few of those sobering statistics,” including the number of crashes and deaths.

“I have concern with it,” he said. “I plan to bring it up at the Board of Police Commissioners at the next opportunity.”

“I think it’s important for us to actually maybe have a moment of reevaluation as to do we really think we’re safer if there’s a high-speed chase down the streets? And maybe the dude who held my mom up at gunpoint and stole her car gets caught. But maybe my mom driving home, she gets hit and killed. It’s tough.”

National law enforcement leaders and experts have said police vehicle pursuits are dangerous to the public and should only be allowed in cases where a violent crime has been committed and there is an imminent danger. They say fleeing suspects often slow down when they are not chased, lessening the hazard.

Kansas City Police Department officials declined to sit down for an interview or to answer questions about the two deaths resulting from the police chases in 2022.

Capt. Corey Carlisle, who recently served as a spokesman for the department, said in a written statement that the department “takes car pursuits and our responsibility for public safety very seriously.”

“Our desire is to not have to chase anyone,” Carlisle wrote. “But sometimes a person must be apprehended. And when that decision is made, we do (chase) with a focus on mitigating risk to everyone.”

Taxi passenger killed in crash

The events that ultimately led to the police chase and crash that killed Miller began March 17, 2022, when a woman reported a robbery to Kansas City police.

She said she had posted her 2010 Dodge Caliber on Facebook Marketplace and met up at a gas station with a potential buyer she described as a man in his early 20s.

They took the car for a test drive, she recalled, and the man got out to talk on the phone. Then she heard a gunshot.

The woman exited the car and saw the man was holding a black pistol and demanded the vehicle’s title. She did not give it to him, but he got in the car and took off, a police officer wrote in a report.

Six days later, officers saw a car matching the description of the stolen Dodge near East 45th Street and Cleveland Avenue. Two other officers, Kyle Conkling and Marco Olivas, who were closer, began chasing the car north.

The driver, who turned out to be a juvenile, ran several stop signs and red lights and drove into oncoming lanes of traffic. Conkling wrote in a report that the stickers on the vehicle, and lack of a license plate, matched the description of the stolen Dodge in the robbery report.

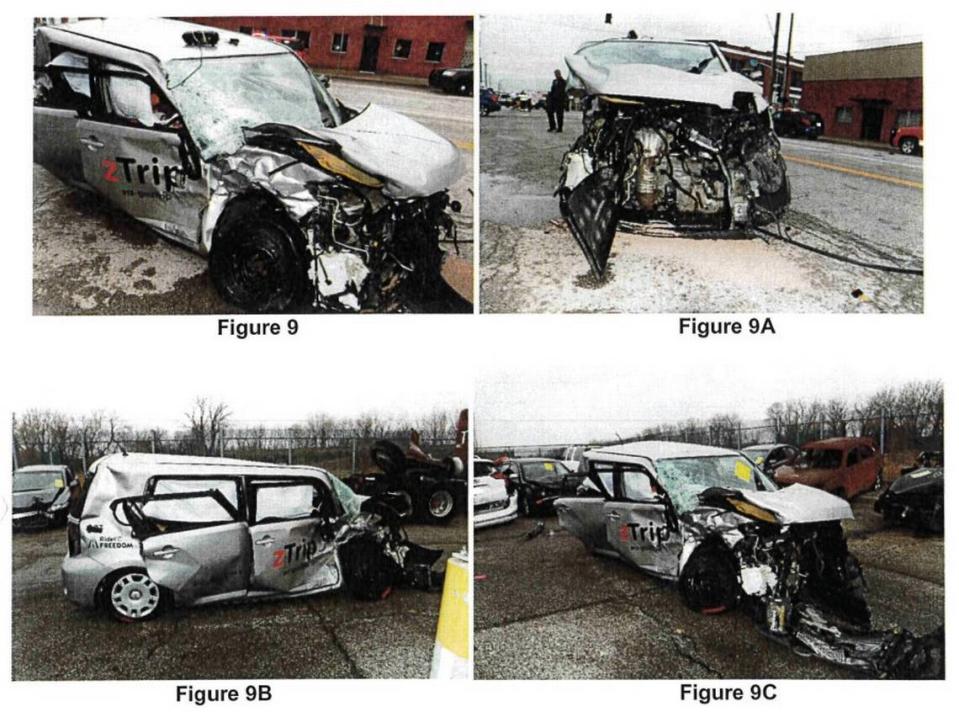

The chase continued north for several blocks until the teen slammed into the taxi at East Truman Road and Prospect Avenue.

Dashboard camera video shows officers speed down Prospect and come to a halt near the two smoking vehicles.

The fleeing driver was going 78 mph one second before the collision, according to a crash report.

Miller was thrown 57 feet.

One officer rushed towards her while others apprehended the driver. Body camera footage shows the officer approach Miller and radio in that someone is unresponsive.

“Ma’am, hey, can you hear me?” he says. “Hey, stay with me OK, don’t move.”

He keeps talking to her.

“Hey, can you hear me sweetheart? Can you hear me? Just hang on, the ambulance is almost here.”

As ambulance sirens blare, another officer leans down and feels for a pulse. He shakes his head “no.”

The 17-year-old driver and a passenger in the fleeing car were taken into custody and transported to Children’s Mercy Hospital. In October, the driver was charged as an adult with involuntary manslaughter.

Court documents said he told a detective he had paid a man $1,500 for the Dodge a day before the chase. He has not been charged with stealing the vehicle.

His attorney declined to comment, citing the pending case.

Conkling and Olivas, the officers involved in the chase, did not respond to requests for comment. Olivas previously came under scrutiny for his part in pulling over a Black Kansas City police detective in March 2021. The detective said it was a case of racial profiling and sued the department.

Kansas City police chase policy

The Kansas City Police Department’s policy on chases allows officers to initiate a pursuit when “there is a reasonable belief that the suspect vehicle or occupant(s) presents a clear and immediate danger to the safety of others.”

One of the factors in that decision is if a dangerous felony has been committed.

While the armed robbery would fall within policy, Burmeister said, a chase six days later means officers don’t know who is behind the wheel.

“The immediate threat has dissipated,” he said, adding that he believes the policy should be more narrowly defined.

Kansas City Police Department's policy on pursuits by The Kansas City Star on Scribd

Lucas also said he supports reviewing the police policy.

Kansas City police officers engaged in 98 chases in 2022, according to department data.

Thirty-eight percent ended in a crash, the second highest rate in the metro after the Wyandotte County Sheriff’s Office, which recorded three crashes in a total of four chases, according to an analysis by The Star.

Fifty-six percent of the KCPD’s chases occurred in residential areas, 31% were on the highway and 12% took place in business areas. Like the pursuit in Miller’s death, most chases began east of Troost Avenue.

Carlisle said police chases were not conducted selectively on the East Side of the city.

“The decision not to pull over for a lawful police stop is the decision of the driver,” Carlisle said. “To suggest lawful enforcement action is targeted in one area of the city is not an accurate characterization.”

Missouri court rulings

A decades-old Missouri Supreme Court ruling has dominated how litigation has played out in the state, making it challenging to hold police departments accountable for their role when fleeing drivers hit innocent bystanders.

In July 1994, Michael and Daniel Stanley were struck by a van fleeing from Independence police and died.

Their family sued the city, claiming the officer acted negligently. In 1999, the Missouri Supreme Court concluded that “there is no way to tell whether the collision would have been avoided if the officer had abandoned the pursuit after initiating it.”

The Missouri Court of Appeals has upheld that plaintiffs generally can’t prove causation between officers’ chasing and a crash.

“The court’s saying basically, this bad guy could have been going this speed anyway,” said Jamie Walker, a Kansas City-based attorney.

Local attorney Michael Foster once wrote a memo to a client explaining why they didn’t have a strong case against the Kansas City Police Department after the man was hit by a fleeing driver.

“You have a really high burden to show that the police screwed up,” he told The Star, citing the Stanley case.

Foster said several factors have to be weighed against potential monetary damages they could be awarded, including the seriousness of the victim’s injuries and often costly expenses for pursuing a lawsuit like expert testimony.

Another factor includes whether police violated a department policy and the underlying reason for the chase.

Foster said he has turned down a few cases involving police chases.

That often means a difficult conversation with clients.

“I wish there was more we could do,” he said. “We’re limited.”

As in Miller’s death, that can mean only collecting $25,000 from uninsured motorist coverage, something Foster urged drivers to sign up for.

Lawsuits have not been filed in Miller or Campbell’s deaths, according to Capt. Jake Becchina, a spokesman for the Kansas City Police Department.

In some cases, attorneys have won large settlements for their clients, but the circumstances have to be particularly egregious. Locally, Independence has paid out six figures multiple times after fleeing drivers have injured or killed uninvolved motorists.

Liability increases when police themselves hit innocent bystanders. Kansas City police paid out a $1 million settlement after an officer pursued a driver going the wrong way in 2020 and hit a car, injuring three people including a juvenile. The scales also tip when police intervene in some way, as was the case last March when a driver fleeing Independence police ran over stop sticks, lost control and struck two people on a motorcycle, killing them both.

Lucas said legal settlements are never a good use of public funds.

“I think what you should take from every legal settlement, whether KCPD or here at City Hall, is say ‘What did we do wrong?’ And make sure it doesn’t happen again,” he said.

Kansas City attorney Doug Horn represented a man who was hurt in a 2010 crash involving Kansas City police, who were chasing a stolen vehicle in patrol cars and tracking it by helicopter. His client, Joe Frazier, was injured when the fleeing driver crashed into the vehicle Frazier was riding in.

Frazier sued, alleging the officer acted with negligence and recklessness.

The claims failed before the Missouri Court of Appeals because of the Stanley case. Horn said the speculative nature of the Supreme Court’s decision — that a suspect could still drive fast or recklessly absent a chase — was “total bunk.”

“The reason there are police chases is because police are chasing,” he said. “The police pursuit puts an urgency in their attempts to get away.”

Dennis Kenney, a professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice who has been studying and reviewing police pursuits for more than 20 years, came to a similar conclusion.

“While it’s true that the responsibility rests with the person who’s fleeing, the officer’s actions and decisions directly impact what that suspect is likely to do and the level of risk that suspect is likely to assume, which obviously puts those innocent people at risk,” Kenney said.

Horn said that police departments themselves recognize the dangers.

“Police departments have responded to this whole police chase thing with more restrictive policies because they know that their pursuits are dangerous,” he said.

Locally, the Grandview Police Department, Lone Jack Police Department and Jackson County Sheriff’s Office have tightened their policies after serious crashes.

Horn called the Stanley decision antiquated. At the time, there was stronger political support for protecting the police, he said. Now, there is more scrutiny about policing itself, in addition to pressure from police organizations and insurance companies to have tighter restrictions on chases. There are also more alternatives to chasing with newer technology, such as GPS tracking.

Over the years, he has turned down other chase cases because of the likelihood that they would fail. One of the factors was the duration of the pursuit — the shorter a chase, the weaker the link to the outcome.

But Horn is optimistic that the tide will eventually turn in Missouri.

If he was presented with Frazier’s case today, Horn said he would take it.

“I would love the opportunity to overturn Stanley,” he said. “But the cost of that comes in a life or a serious injury.”

How we reported this

After two innocent bystanders were killed in a police chase in March in Independence, Star reporters began looking into law enforcement pursuits in the Kansas City area. Over the next nine months, the reporters filed more than 140 public records requests with more than 60 local law enforcement agencies across the metro. They gathered police pursuit policies and documents recording chases, crashes and injuries over a period of five years.

Reporters also obtained investigative case files from serious and fatal wrecks, including dashboard camera recordings. They reviewed court documents from lawsuits and legal settlements. In all, the team examined more than 4,500 pages of documents, allowing them to identify patterns in police pursuits and practices in the metro.

They also spoke with more than 60 people, including innocent bystanders who were injured in police chases, families of victims killed in pursuits, police officials, attorneys and academics who have been studying the topic for decades. They interviewed a person in prison serving a sentence for killing four people in a crash during a police chase in 2018.

The project is published in a series of eight stories, with videos of interviews and crashes, as well as infographics showing the scope of police pursuits in the metro.

Credits

Katie Moore, Glenn E. Rice and Bill Lukitsch | Reporters

Emily Curiel and Nick Wagner | Visuals

Monty Davis | Video Editing

Neil Nakahodo | Illustrations & Design

David Newcomb | Development & Design