‘Mommy, I’m in so much pain:’ Florida prisoners write home about COVID-19 ordeals

“Mommy, I’m in so much pain … I just had to crawl to the door and knock on it over and over to beg for another tylono [sic],” wrote one inmate to her mother. “I’m still on the floor just crying cuz it hurts.”

“No staff has been coming to see me at all,” an older inmate wrote to her daughter. “I don’t know how they expect the oxygen to get better when you don’t have no plugs in here to use the machine.”

Accounts of inmates shared with the Miami Herald, sometimes on condition of anonymity, reveal the impact of the coronavirus as it surged through Florida’s prison system. As of Monday, 17 prison deaths had been attributed to the virus, and more than 1,500 inmates and 290 staffers had been infected.

Nearly 5,000 other inmates were in some kind of quarantine or isolation and 90 tests were pending. More than 13,000 tests had come up negative.

The rate per 10,000 of COVID-19 cases among Florida’s inmates is roughly six times that of the rate among the state’s general population. And yet it arguably could have been much worse: The rate of prison deaths attributed to COVID-19 is 34 percent higher than in the overall state population — a surprisingly low percentage considering the high rate of infection behind bars.

Among state prison systems, Florida ranks middle of the pack in rate of infections, according to the Marshall Project, a Pulitzer Prize-winning nonprofit news operation that tracks prison issues. Among its peer systems — the three largest in the country — Florida has more deaths than California but fewer than Texas.

Florida Department of CDC spokesperson Michelle Glady said that both Centurion, the private healthcare provider serving the state’s prison, and the correctional system in general have done an exceptional job of caring for inmates with COVID-19 and that Centurion is always “held accountable for care in line with evolving national standards.”

“To suggest that these healthcare workers are providing inadequate care to their patients is patently false,” she said. “The level of care and attention they have provided to the inmate population has been outstanding.”

The speed at which the virus can spread in prisons — where inmates are quartered in packed dorms — is perhaps best illustrated by the outbreak at Homestead Correctional Institution, a women’s prison south of Homestead.

In early May, when three inmates showed COVID-19 symptoms at the facility, the staff tested them but assigned them to three different dorms while waiting for the results, a Homestead inmate’s mother said.

On May 10, the facility reported two inmates and one staff officer with positive tests. Two days later, that number had grown to 73 inmates and two staffers. On May 17, 231 inmates and 19 staffers were reported infected.

Ear aches and swelling

The inmate’s mother said that her daughter first started getting ear aches, which nurses dismissed. When she complained that her mouth had become swollen and she couldn’t swallow, they gave her ear drops and performed a COVID-19 test, which came up positive.

Nurses then gave her a floor-mat and isolated her in a confinement cell used for disciplining unruly inmates and locked the door, the mother said. She was told by her daughter that was standard FDC practice during the outbreak. The mother said she frantically called prison officials to ask why her daughter’s door needed to be locked, but they wouldn’t give any answers.

She had to bang on the door, cry and starve herself just to receive basic medication like ibuprofen and Tylenol, her mother said.

“I can’t believe how I’m being handled,” the daughter wrote in an email her mother shared with the Herald. “They haven’t even let me shower.”

Only after repeated calls to the facility was she able to get her daughter transferred to the infirmary.

As of Monday, June 7, Homestead lists 301 inmates and 31 staff members as positive for the coronavirus.

Among them is 64-year-old Gloria Taylor, serving her 30th year of a life sentence for trafficking less than four tablespoons of cocaine. She was sentenced as a “habitual offender.”

“My results are back and I am positive,” she wrote to her daughter, Jemena Taylor, on Mother’s Day. “I love you Jemena and thank you for everything.”

After Gloria Taylor was put in an isolation cell, no staffer or nurses checked up on her regularly, Jemena said. Gloria Taylor said she was given cold ham sandwiches with just one hot meal per day.

“I haven’t had a drink of water since morning nor have they given me a shower,” Taylor wrote her daughter. “Jemena, no staff has been coming to see me at all.”

Jemena Taylor said that no one from the FDC contacted her about her mother’s health though she is listed in all her medical information release forms. Nor, she said, did any ranking officer or doctor receive her calls. It was only after she started posting her mother’s emails on social media that Taylor was taken to a hospital.

Last month, the civil rights non-profit Southern Poverty Law Center sued FDC for records explaining how the department is handling the pandemic.

“Prison officials have had months to prepare for an outbreak and they should have prepared appropriate housing for people to quarantine and receive treatment,” said Kelly Knapp, senior attorney with the SPLC.

“Forcing people with COVID to sleep on mats on the floor or in disciplinary isolation is cruel and inhumane.”

FDC suspended visitation, implemented screening for those entering its facilities and stopped non-critical inmate transfers in early March. But the department struggled to conduct adequate testing of inmates in those crucial early days. For weeks, the prison system refused to disclose to journalists how many tests had been conducted.

As cases across the country surged, medical experts and prison reform advocates called for the release of low-level offenders and elderly inmates.

Some states did that. Florida did not. While FDC Secretary Mark Inch publicly promised in March that the department was following CDC guidelines, there was at least one reported incident where an inmate — at Martin Correctional Institution — was punished for wearing a mask.

On April 11, FDC announced that several healthy inmates had been tasked with making cloth masks. But initially the masks were reserved for “correctional officers, probation officers and staff” and only later could inmates get them.

After the number of inmates with COVID-19 at Tomoka Correctional Institution in Daytona Beach soared from seven to 38 on April 17, healthy inmates at Tomoka were transported to Columbia Correctional Institution in Lake City the next day, where at the time no inmates had tested positive for the illness.

Loved ones of inmates at both Tomoka and Columbia told the Herald that some days later two inmates who were transferred were found to have the virus. By May 1, the first Columbia inmate had tested positive. As of Monday, June 8, that number had grown to 25.

Inmates and their loved ones say the crisis has been compounded by the quality of care inmates have been receiving from private healthcare companies for years.

Rick Scott, a former healthcare executive, pitched saving taxpayer dollars by turning over the prison healthcare system to private firms when he ran for governor in 2010. In 2012, after he won the job, Florida signed deals worth $1.4 billion with Wexford Health Sources and Corizon, Inc. to provide health services in FDC facilities.

Within months, the monthly inmate death rate shot up to a 10-year high and FDC and the two companies were swamped with lawsuits alleging negligent care and substandard medical practices. Both companies pulled out of the state in mid-2018, leaving the path clear for another healthcare giant, Centurion, to win a $2.2 billion contract without any competition.

State campaign finance records show Centurion’s parent company, Centene Corp., has been a generous contributor to the Florida GOP, the state’s dominant party. It contributed around $1.5 million to the state Republican Party from 2007 to 2020. It also gave $380,000 to the Florida Senatorial Campaign Committee from 2015 to 2019.

The company contributed $160,000 to Gov. Scott’s political committee Let’s Get to Work between 2013 and 2018, and in 2014 gave $175,000 to the Republican Governors Association Florida PAC, most of which went to help re-elect Scott.

Meanwhile, healthcare woes have continued.

A recent audit found that the decision to privatize prison healthcare is costing the state $40 million more per year than it would have cost to keep the service in-house. Forbes reported in 2018 that 181 Florida inmates did not get treated for Hepatitis C even though they qualified.

More recently, FDC reported that its health services budget was underfunded by $55 million in fiscal year 2018-19.

Centurion Healthcare declined to comment.

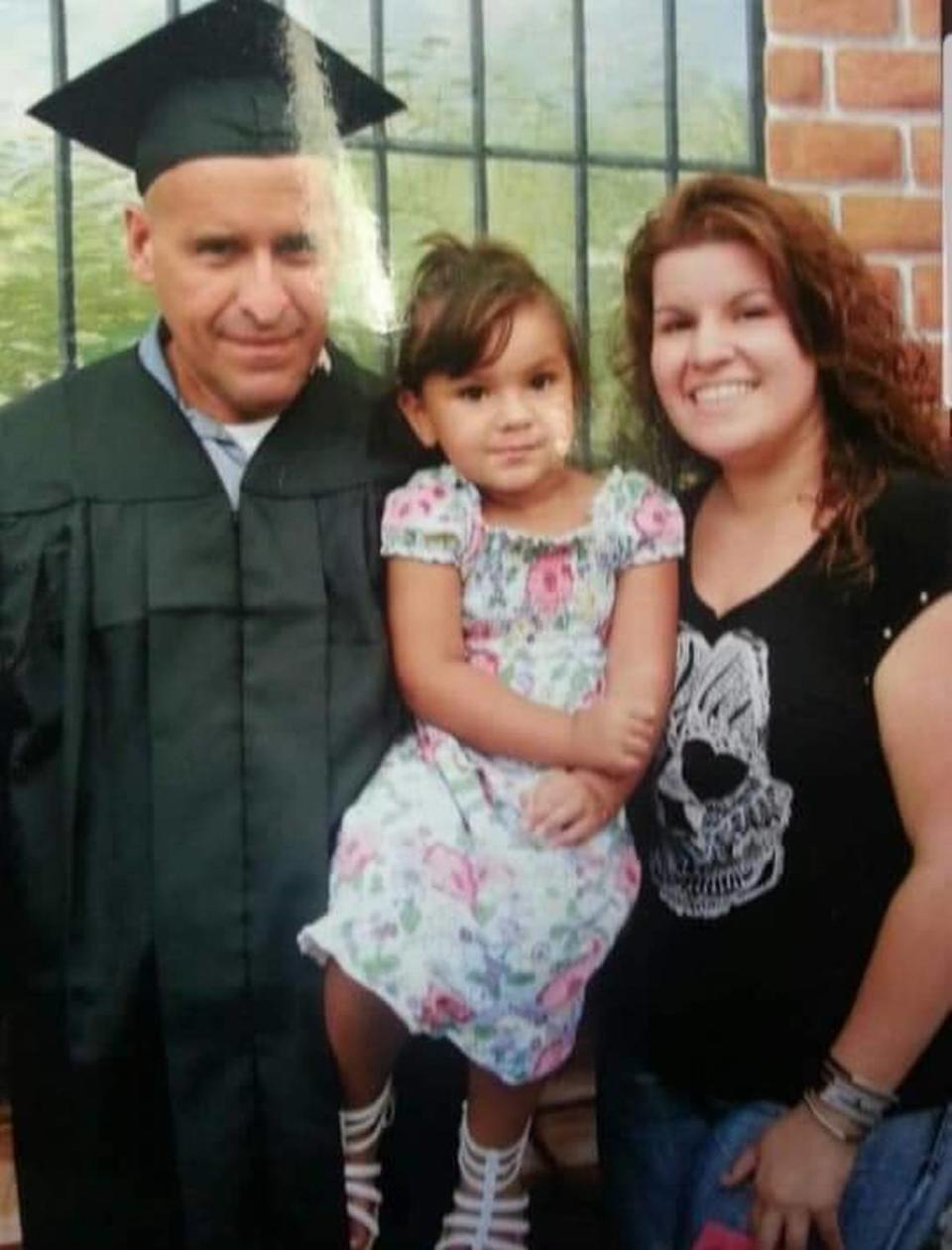

Henry Camacho, an inmate at Sumter Correctional Institution, complained of chills, shortness of breath and loss of taste in late-April. He tested positive for COVID-19 a week later — one of among 102 inmates who were found to have the virus at the time.

Carmen Sanchez, a family friend, said that for three days Camacho was in an isolation cell and not given much care beyond regular monitoring of vitals. The inmate’s daughter, Chrystal Camacho, said FDC did not notify her that he had contracted the virus. She learned of his condition from his dorm-mates.

“The prison was very difficult to deal with to get any kind of update or information,” Chrystal Camacho said.

With his condition deteriorating, prison staff moved Camacho to a hospital, where he was placed on a ventilator. Fearful he would die, Doctors gave his daughter a “death-bed visit” to see her father one last time at the hospital, Chrystal Camacho said.

Miraculously, after being on the ventilator for two weeks, Camacho’s condition started improving and he was taken off it. Despite protestations from father and daughter and the fact that he could still not swallow food or move, he was transferred back to Sumter less than two days later.

“In what world are you taken out of being on a ventilator for two weeks and discharged on your second day off of it?” said Chrystal Camacho “It’s mind-blowing to me.”

Michelle Glady, the prison system spokeswoman, rejected the idea that FDC was responsible for the decision in any way.

“Once at the hospital, the decision to discharge an inmate from outside hospital lies with hospital staff,” she said.

People should stop treating inmates “as a number” and acknowledge that they too have a right to proper medical care, Chrystal Camacho said.

Her father died on May 16.

“He pulled through the worst part of it but because he didn’t get proper medical care to continue his recovery, it cost him his life,” she said.

At 55, Camacho is thus far the youngest Florida inmate to succumb to COVID-19.