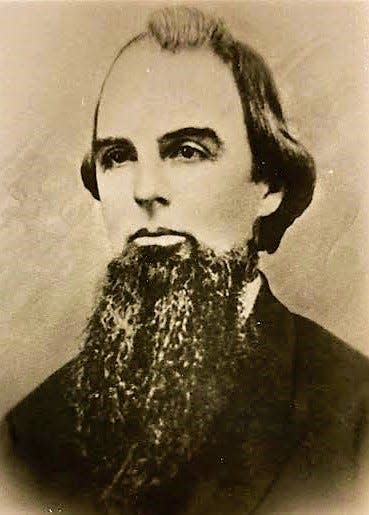

Monday Mystery: A rising political career comes to a rough ending for Foster Blodgett Jr.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

If you go to Atlanta's historic Oakland Cemetery you might look for the grave of Foster Blodgett Jr., who was a two-term mayor of Augusta, a city councilman, a judge and even Augusta's postmaster.

You might wonder what he's doing there in an Atlanta cemetery plot not far away from golfer Bobby Jones.

You might also wonder why his gravestone gives his date of death as 1887 when the newspaper covered his funeral 10 years earlier with two former governors as pallbearers.

You might even wonder why a guy with a name like a Harry Potter character (and a beard to match), is so forgotten back in the town where he was born, raised and very politically active.

Augusta historian Dr. Ed Cashin Jr. once explained it by simply calling Foster Blodgett "perplexing."

More Monday Mystery: An Augusta investigation followed death of 'Gone With the Wind' author

And: Monday Mystery: What was behind the creation of the Georgia Guidestones?

He was born in Augusta in 1826 and his father – Foster Sr. – was a war hero.

Foster Jr. became a member of the city council and would twice be our town's mayor. He also held the job we now refer to as probate judge, a duty he quit to serve as a Confederate artillery officer.

He was postmaster, and chosen – but not seated – for the U.S. Senate.

After the Civil War, Foster Blodgett was one of the most active politicians in Georgia and part of what was then called the "Augusta Ring," that also included two governors Rufus Bullock and Benjamin Conley. Unlike Bullock, from New York, and Conley, from New Jersey, Blodgett was the native Augustan, and said to be charming, well-spoken and affectionate enough that he fathered 11 children.

However, when he died in 1877 of typhoid fever in Atlanta, he was under criminal indictment and trying to make a living as a traveling salesman.

What happened?

Politics.

Despite being an experienced operative, Blodgett couldn't navigate the chaos that was Georgia government during Reconstruction after the Civil War. Cashin called him the "tragic figure" of the period, because almost every job, office or initiative he tried failed.

The first might have been when he joined the Republican Party, which had practical advantages in both Washington and with military administration in Atlanta. That was where Blodgett hurried in 1867 to successfully gain military appointment as Augusta mayor, a job he had held before in the 1850s.

Divisions among Georgia Republicans, however, became a problem and Blodgett attracted a bitter local rival named J.E. Bryant, a transplant (some would say carpetbagger) from Maine.

It was Bryant who traveled to Washington to convince President Grant to rescind Blodgett's appointment as Augusta postmaster because he had not included his Confederate artillery service on his resume.

Grant fired Blodgett and gave Bryant the well-paying postmaster job.

Still, Blodgett had the backing of Gov. Rufus Bullock. (Blodgett would name a son Rufus.) The governor gave him a plumb job, running the state railroad, which quickly began to lose large sums of money. Critics said Blodgett, Bullock and others were diverting the money to themselves.

Most subsequent investigations, however, found the railroad in dismal shape and in need of expensive upgrades.

The biggest disappointment was probably Blodgett's failure to become a U.S. senator.

At the time U.S. senators were not elected by voters, but selected by state legislatures, and in 1870 Georgia's Republican lawmakers chose Blodgett. It was the job most said he really wanted

Georgia Democrat lawmakers, however, refused to take part in the vote and senators in Washington decided they would not seat Blodgett, advising the Georgia General Assembly to choose another candidate.

When Republican power waned in the early 1870s, the Georgia Democrats returned with a vengeance. They went after the "Augusta Ring," Bullock first, pursuing embezzlement charges of state funds. The governor resigned and fled to New York. The charges were political and when Bullock returned years later and faced trial, a jury acquitted him after deliberating only 30 minutes.

Conley, who as president of the state Senate became governor when Bullock bolted, but served only a few months before his term ran out. He stayed in Atlanta, however, became postmaster, and when he died years later, he was brought back to Augusta and buried in Magnolia Cemetery.

Blodgett also left the state, moving his family to Newberry, S.C., where his wife ran a boarding house and Blodgett tried to scratch out a living as a cotton farmer and traveling salesman.

A reporter who saw him around this time described him as bent like an old man of 75 or 80, even though he was only 50.

Perhaps it was because he was awaiting a trial. It was set in Atlanta, where Bullock, Blodgett and a third man were charged in a swindle involving $42,500 appropriated for railroad cars that were never delivered. Blodgett caught typhoid fever, seemed about to recover, then died two months before the trial.

Prosecutors spitefully left his name on the indictment, and Blodgett didn't live to hear himself eventually exonerated.

When he died the obituary in The Chronicle, a frequent critic, was full of praise.

The Atlanta Constitution – although an ardent Democrat paper of that era – also saluted him, writing, "Foster Blodgett was a man of warm, personal attachments and of a genial nature that no political acrimony could disturb."

Foster Blodgett Jr. was buried and then not only forgotten, but misplaced.

It seems the cemetery workers and tombstone engravers got confused when Blodgett's young son died 10 years later and mixed up the death year on new markers. That's why Blodgett's Oakland Cemetery tombstone says that the "MAYOR OF AUGUSTA GA. FOR TWO TERMS" died in "1887."

Cemetery workers are also believed to have accidentally switched Blodgett Jr.'s grave with his son's site.

For an Augustan of many achievements Foster Blodgett Jr. might have deserved better, but didn't get it.

Bill Kirby has reported, photographed and commented on life in Augusta and Georgia for 45 years.

This article originally appeared on Augusta Chronicle: Streak of bad luck doomed career of Augusta politician after Civil War