The Monday After: Remembering Magnolia Mills in 'The Good Old Days'

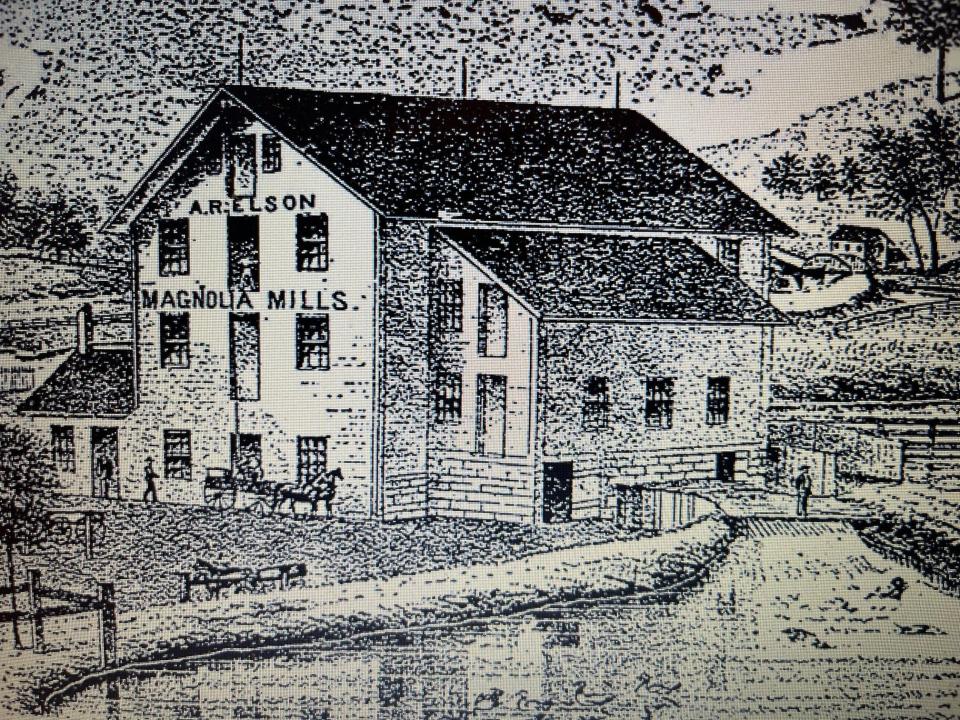

Almost a century ago, the Magnolia Flouring Mills − then still called the A.R. Elson Flouring & Grist Mills − already qualified as a site that could be profiled in the Sunday Repository's column called "The Good Old Days."

"For 95 years the Elson Mill has ground into flour grain grown on farms around Magnolia," wrote Jean Stophlet in a "Good Old Days" piece published in the Repository on April 28, 1929. "The machinery still turns by power furnished by a water wheel concealed beneath a part of the building; and all these years it has been operated by one family − the Elson family.

"There is little doubt that this mill, only a few miles from Canton, is the oldest in the state of Ohio still operated, and certainly it is one of the only mills in the country which has remained in the ownership of one family for almost a century."

The Elson family since has passed on control over the mill, which now is maintained by Stark County Park District. The park district has sought to be a good steward of the structure and preserve the history of the agricultural era it represents.

A recent article by Paige Bennett in The Canton Repository reported that Stark Parks had obtained a $571,000 state capital grant for continued redevelopment of Magnolia's grain mill.

"We've done lots of rehabilitation to the building itself, but we really wanted to make that building accessible and usable for the general public," Sarah Buell, projects and administration manager at Stark Parks told Bennett for an article published in the Repository on Dec. 2, 2022. "We have huge dreams about getting access to all levels of the building, but I think with the funding level, we're going to focus on that first floor experience."

In light of the financial assistance, it seems appropriate to look back at the historical significance of the familiar red landmark in Magnolia, and to learn what the "experience" of being in the mills might have been like long ago.

Founded by village resident

Magnolia Flouring Mills identifies itself with large black-and-white letters on its front. Above that name is the moniker of the patriarch of the family who founded it, A.R. Elson Co. And, at the peak of the building, the date in which the mills went into operation − 1834 − is boasted in bright white numbers.

"(A.) Richard Elson built the mill and named the town that grew up around it Magnolia," recalled the 1929 article, noting that Elson came from Virginia to Ohio and sought his fortune "by building flat boats at Steubenville on which he transported cargos of flour and pork down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers to New Orleans."

"His money carefully concealed in his buckskin clothing, he walked the thousand miles back to Steubenville, there to start the while thing over again," wrote Stophlet, repeating a difficult to prove or disprove story that has been passed down through the years. "As he walked he breathed in the fragrance of the magnolia blossoms of the forest land, and he dreamed a dream that some day he would grow wheat and grind it into flour − Magnolia Flour."

Stophlet wrote about how Elson "purchased and homesteaded land in the valley of the Big Sandy." He built a saw mill and the flouring mills there, dammed the river, and used the current for powering the mills.

After the death of Richard Elson, the writer noted, the mills were operated by his son Augustus, and then Augustus' sons, Frank, Richard and John.

Represented 'bygone era'

By the time the Repository's writer-photographer Paul Geary wrote about Elson Mills in 1970, operation had passed to Mack Elson, a great-grandson of the founder.

Though much had changed, technologically, Geary noted, the atmosphere surrounding the mills had remained the same.

"In a dark corner, deep in the basement of the A.R. Elson Co. flour mill, is a silent reminder of a once-thriving pioneer industry," Geary wrote. "Relied on to drive the grist mill, the huge water wheel no longer is needed for power."

Nor were horse-drawn wagons delivering unmilled grain anymore, he wrote. And, the old mill pond was but a memory.

Still, he observed, "the smells and sounds escaping from the old red mill today are much the same as when it first opened."

Mack Elson provided Geary with a chronology of changes at the mills.

"The original grist mill was transformed to mechanical grinders in 1883," Elson recalled, noting that it was 14 years before he was born. "Electricity was installed about 20 years ago. Before that, the mill was operated by steam and natural gas engines."

The improvements helped for a time to keep the flouring mills in business, he noted, but they left the operation--capable of producing 1,000 pounds of flour an hour, but operating at only 30 percent that rate--standing almost alone in an industry that was evolving toward larger mills.

"Small mills are almost a thing of the past," Elson told Geary.

Mills operation continued

Magnolia Flouring Mills still was operating − but just barely − nine years later when Repository writer James Hillibish spoke to the owner.

"As big guys pushed out little guys in the familiar pattern of American business, most rural areas lost their Main Street flour mills by the 1950s − except for Magnolia," wrote Hillibish. "Elson's mill survives, mainly because his family covets permanence over passing economic cycles."

Elson admitted that his milling operation was "much busier" during prior days when the "Magnolia" label was familiar in Ohio and Pennsylvania. But, a handful of years before Hillibish interviewed the owner of the mills,"the incessant chatter of the grinders fell mostly silent," according to the writer.

"We still mill some whole-wheat flour, some corn meal and feed grains, but it's nothing like the truckloads we once made."

Nevertheless, the atmosphere − that lingering sound and smell of Magnolia Flouring Mills − helped the establishment seem familiar. "The mill wreaks of permanence," Hillibish wrote.

In his article almost 45 years ago, Hillibish foreshadowed the educational use to which the Magnolia Flouring Mills ultimately would be put.

"Checking the hand-hewn cellar timbers and pondering unknown initials cut there years ago, Elson said there's sporadic talk about making the mill a public museum," Hillibish wrote. "Already it's a popular spot for tours of schoolchildren, and many a traveler stops by for photographs."

Additional descriptions offered

Other Repository writers have added to the discourse about Magnolia Flouring Mills in years since Hillibish visited.

In January of 1989, Repository staff writer Jan Kennedy vividly told newspaper readers about the original process in which Elson mills produced flour during an era when, as Mack Elson told him, "bread was a major part of a family's diet and the farm wives baked it several times a week."

"Richard Elson prided himself in buying all the wheat produced in the area at the highest market price," Kennedy wrote. "It was shoveled into a wagon-height chute. As it dropped, it ran over a cleaner and into a cart, which could be rolled onto a scale. From there, it was taken on a conveyer line upstairs to a holding bin.

"When it came time to grand the wheat into flour, the grain was fed into the eye of the millstone. The lower millstone, called the bed stone, was stationary. The upper millstone moved and could be adjusted up or down, depending on the desired fineness of the flour. As the grain was ground, it was forced to the outer edge of the bedstone and collected in spouts that transfered it into barrels or bags."

Success for the mill was "not the result of the Sandy-Beaver Canal," noted Kennedy, "but the origins of each coincided." Planning for the canal began only a handful of years after Elson Mills began operation, and the first boats transporting cargo, including Elson's "Magnolia" flour, started moving on the canal in the middle of the 1840s.

Finds place in history

It was in the spring of 2000 when Repository staff writer Wuyanbu Zutali reported on the attempts of the owners of the Elson Flouring Mills in Magnolia − a fifth generation of Elsons represented by Augustus "Gus" and Jolane Elson − to place the Elson Flouring Mills in Magnolia on the National Registry of Historic Places.

Among other things, the application by the Elsons needed to show, among other things, that the site was "associated with the lives of people significant in the past" − it frequently was visited by President William McKinley − and also "was associated with events that made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history."

About the time Zutali's article was published, the Ohio Historic Site Preservation Society was meeting to decide if it would nominate the mills for the registry.

The Society approved the nomination. The Magnolia Flouring Mills site, which remained in the Elson family for 171 years, was accepted to the National Registry of Historic Places later in 2000.

Stark Parks obtained the mills in 2005, and now recognizes it on the park district's website as an historic place to "explore how innovation, transportation, and community connections transformed the Magnolia Flouring Mills from a small town mill to a nationally recognized producer, capable of winning gold medals at two World's Fairs."

The state grant will help pay for renovation of the Magnolia Flouring Mills, a project begun in 2021 to make the site "more inviting and accessible to groups," the website said. Work will proceed according to a master plan by Landscape archited Environmental Design Group and exhibition designers Split Rock Studios.

"The process looked at options for exhibits that could withstand the conditions of the mill," said the Stark Parks website page devoted to Magnolia Flouring Mills, "and developed some concepts to interpret the wide array of equipment, history and pure physics that make the mill such an interesting place to visit."

Reach Gary at gary.brown.rep@gmail.com. On Twitter: @gbrownREP.

This article originally appeared on The Repository: The Monday After: Remembering Magnolia Mills in 'The Good Old Days'