Money ball

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

He’d decided weeks ago, but now it was official. Arch Manning was in the wood-floor gym of Isidore Newman School, a private nondenominational prep academy in New Orleans where tuition runs roughly $27,000 a year, and he was ready to end years of speculation from college football fanatics across the country.

The gym was decorated with Kelly-green banners celebrating state titles the school won in a variety of sports dating back decades. This was late December 2022 and Manning, still just 17 at the time, was wearing a casual white and navy striped golf shirt and a gray zip-up fleece, and his hair was tussled and puffy. He was accompanied by his father, Cooper, and his grandfather, Archie, the former New Orleans Saints quarterback who’s become the patriarch of American football’s royal family.

“I’ve really enjoyed my high school athletic career, just really being a high school student,” Arch Manning said to a local television reporter. The kid has a straightforward delivery and subtle intonations that evoke his famous uncles, Peyton and Eli — which is part of why his recruiting process was such a big deal.

“Newman’s had a great community,” he said. “I’m gonna miss it for sure.”

Because the decision had been made and publicized already — almost everyone was wearing burnt orange University of Texas ballcaps — the official signing day event in the gym didn’t make big national news at the time. But looking back at this moment decades from now, the Arch Manning saga will be something historians point to when they talk about the incredible transformation of college football.

The 6-foot-4 quarterback was so successful in high school — and comes with such a remarkable pedigree — that the university reportedly spent nearly $300,000 on a single weekend recruiting trip to lure him and a few other recruits to Austin. That’s enough to cover the annual salaries of several professors. And sure, that could contribute to enlightening the next generation of American leaders, but a few new professors probably wouldn’t make the university tens of millions of dollars. Successfully recruiting Arch Manning just as the Longhorns football program moves to the most important conference in college sports, though, will bring exponential returns on the school’s investment.

He hasn’t taken a single snap in a college football game, but the younger Manning is already worth a projected $3.7 million in annual name, image and likeness money. Even just a few years ago, that entire concept — let alone those numbers — was unimaginable. And that amount is just for him. The amount of money his presence will bring to the school, in the form of ticket sales, merchandise and brand awareness, is incalculable.

Manning is joining a Texas program that’s going through some changes. The Longhorns will play in the Big 12 for another season, overlapping with incoming BYU, before joining the Southeastern Conference, the most powerful and successful football conference in the country. (The last four national champions have come from the SEC.)

Related

If it’s been a minute since you’ve watched college football, there have been some tectonic shifts in the game’s landscape over the last few years. Bear with me.

Days before this issue went to press, one of the most storied athletic conferences in college sports — the Pac-12 — imploded, with Arizona, Arizona State, Colorado and Utah leaving for the Big 12. They will join BYU, Cincinnati, Central Florida and Houston, who begin league play this year, and bring the total number of teams in the conference to 16, once Texas and Oklahoma depart for the SEC. Oregon and Washington announced they’re headed to the Big Ten, joining USC and UCLA, and bringing that conference to 16 teams.

If that sounds like gibberish to you, suffice it to say that college football as you know it ends after this season. Regional rivalries, tradition, Pac-12 decals, maybe even the Apple Cup. Gone. As of this writing, Cal and Stanford have no idea what conference they’ll even belong to in 2024.

What’s driving all of this isn’t the fans, alumni or, better, more competitive football. It’s money, plain and simple. And the main driver is TV. Television contracts for the biggest schools and conferences are gigantic. The more marquee football programs a conference can put together, the more money it can bring in. The SEC’s latest deal with ESPN is reportedly worth $300 million a year.

Starting in 2024, the national champion will be crowned via a 12-team playoff resembling the NFL’s system. Those games will also generate hundreds of millions annually in TV contracts and ad revenue.

And yes, players can get paid now, too. Not directly from the schools — not yet, anyway. But players can profit from the use of their name, image and likeness (NIL). The change was initiated by a 2021 unanimous Supreme Court ruling that restrictions on “education-related benefits” for college athletes violated antitrust law. That’s why experts estimate that Arch Manning could make nearly $4 million his freshman year.

Football has become an important part of the modern college experience. It’s a way to develop friendships that last a lifetime.

Oh, and like free agency at the pro level, if a college player isn’t happy at a school, there’s a “transfer portal” now, allowing student-athletes to relocate to a new team for every year they’re in college. And it happens every year at virtually every school.

So, what does all of this change mean for these massive, realigning college football juggernauts, where every year the game attracts more money and seems more professional?

And, what’s going to happen to the smaller schools, like Utah State and Boise State, where football games are no less part of the college experience — even if they don’t have TV contracts worth hundreds of millions of dollars per year?

The answer is: It’s complicated.

The college football experience

I understand the problems with college football. My abiding affinity for the sport comes with some reservations. Of course the game is gladiatorial. Every time these young men line up on the field, they’re risking career-ending, life-altering injuries — including less visible but even more dangerous head injuries — at least partially for the entertainment of obnoxious fans like me. There’s also all the uncomfortable professionalization, the social pressure the game puts on young athletes whose frontal lobes are still forming. The entire endeavor is exploitative.

Plus fans like me — I went to the University of Texas and root for the Longhorns — could almost certainly be doing something more enriching with our time than spending several hours every Saturday in the fall gaping at a television, right?

And yet, despite all that, college football is absolutely exquisite.

There are few things in life as dramatic as a tightly spiraling football cutting through the crisp, late-season air of a crowded college stadium in the waning seconds of an undecided game. The joy of a great win, the agony of a painful loss — those feelings are real, even if the game doesn’t really matter, which is why it’s so great. College football is the ultimate escapism.

In a frayed and fragmented society, college football forms some of the only connective tissue that still transcends geopolitical ideologies. It doesn’t matter who you voted for or where you worship. If come Saturday afternoon you root for the same colors, the same goofy mascot, you and I are on the same team.

Related

For these reasons, football has become an important part of the modern college experience. It’s a safe way for young adults to find identity beyond their own families and religions. Football fandom, especially in college, is a way to develop friendships that last a lifetime. Some of my closest friends are people I’ve stood next to during games, yelling and swaying and singing, for more than 20 years.

College football is a wonderful paradox. It’s brutal but beautiful. The premise of the sport is simple — move this ball to that end of the field while stopping your opponent from moving it to your end of the field — but every play involves more moving parts than any human can track in real time.

And yes, college football is ridiculously commercialized. But isn’t that fitting for what’s truly the most American of all sports?

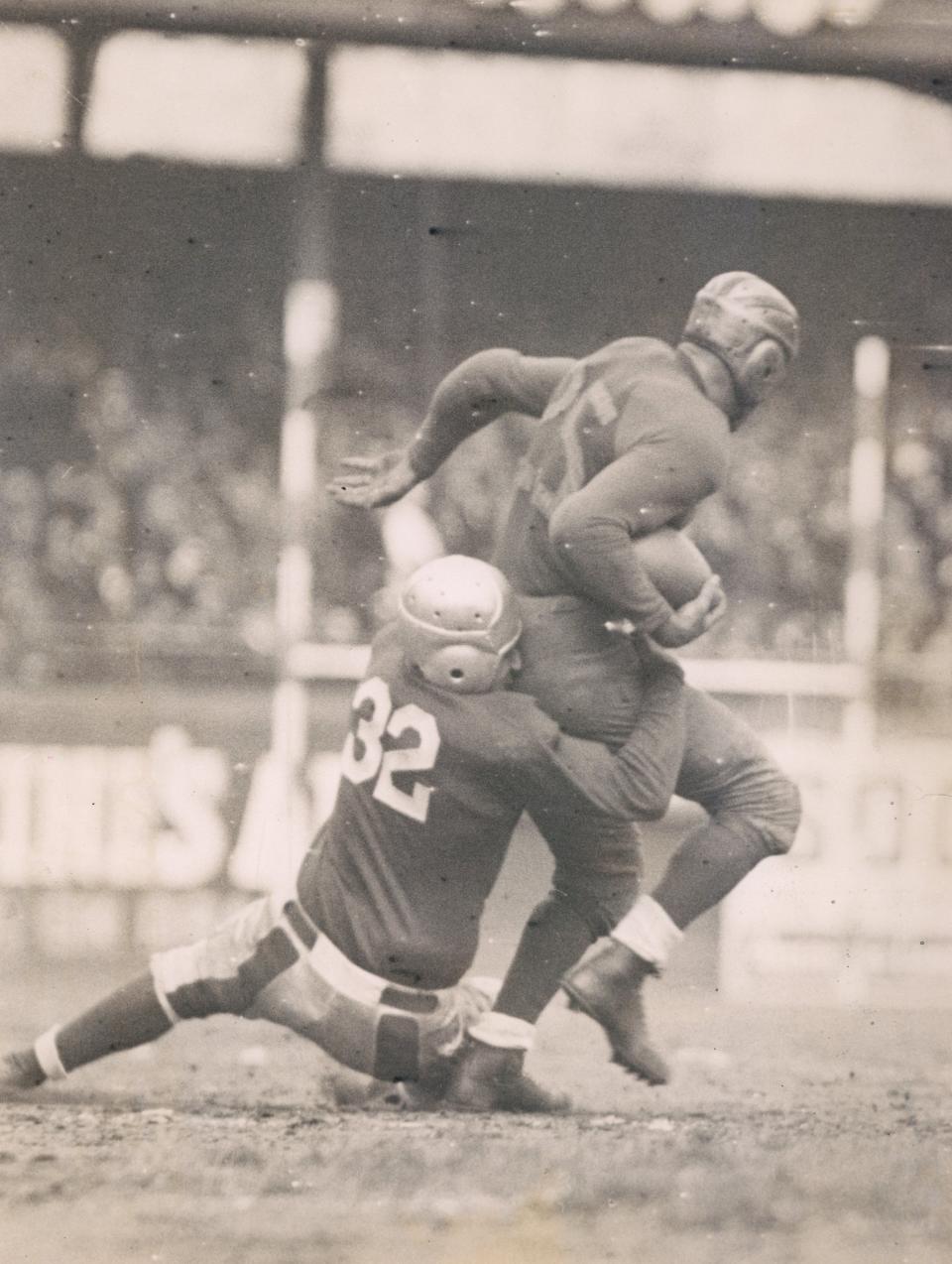

American football was invented not long after the Civil War and quickly became a way for young men who hadn’t fought in battle to prove their toughness. Though the average player was much, much smaller than today, the sport was even more violent. Every play was one team lining up shoulder-to-shoulder directly in front of their opponents in a punishing fight for territory. The earliest tactics mimicked traditional strategies for war and it wasn’t rare for games to end with scores like 6-0.

The game was also fatal. In one year (1905) 19 players died on the field.

And for decades, this muddy, bloody, body-mangling sport was most popular with East Coast elites. The first college football game, in 1869, was between Rutgers and the school now known as Princeton. The Ivy League was the first power conference, and Harvard and Yale were two of the first big programs. The game wasn’t about money. Players weren’t looking for endorsement deals or a chance to play professionally. It was instead considered integral to the development of a sophisticated man, with invaluable lessons about teamwork, humility and community pride.

Several U.S. presidents played college football. Dwight Eisenhower was a halfback at West Point in 1912, before an injury ended his playing career. His successor, John F. Kennedy, played at Harvard, but never made the varsity roster. Gerald Ford was a center and linebacker at the University of Michigan on two national championship teams in the 1930s. He was so good that he apparently had offers to play professionally. Ronald Reagan was a lineman at Eureka College in Illinois, though his more famous connection to the game came a few years later, when he portrayed Notre Dame football great George Gipp in the 1940 film “Knute Rockne, All American.” That’s when Reagan uttered the line “win one for the Gipper.”

Now, the game is obviously different. The sport itself has morphed from a frustrating series of barely-moving scrums into a high-speed, wide-open sequence of colliding acrobatics. But as much as the forward pass changed the game, everything surrounding college football has changed even more. Multinational corporations clamor to get their names on big matchups. Every game is an event, a production.

If you wanted, you could probably watch just about any college football game from the comfort of your living room — and every timeout you’ll see a commercial for a new car or a new movie or a way to insure your life against mayhem.

Going to a game in person is an act of communion. College football stadiums are monoliths, sure to be studied by future archeologists and visited by tourists the way people today flock to the Colosseum in Rome. The sport has become the focal point for the large communities that build up around universities both big and small. A home game at almost any school is now an on-campus festival, replete with elaborate tailgate parties, corporate sponsorship and often a stage featuring live performances.

And somehow, the injection of so much money — and so much cynicism — has made college football even more American.

The future of college football

Last year, ESPN, the official television partner of the College Football Playoff, surveyed more than 200 college football coaches, players and administrators about the future of the sport. Respondents were allowed to offer anonymous feedback, and the results were revealing.

A few notable trends emerged. Roughly 80 percent of respondents said that they believe universities will pay athletes directly within the next decade. Nearly 75 percent said they think the sport will become more like the NFL. And almost everyone surveyed (98 percent) said they thought the conferences would continue to realign.

Right now, there are five “Power” conferences. (Pac-12, Big 12, Big Ten, ACC, SEC.) It seems likely that the biggest, most valuable football programs will keep joining forces. Think of merging conglomerates cornering an industry. It’s possible that the playoff tournament at the end of the season will continue to expand and bowl games become purely ceremonial. Maybe there will be more limits on the transfer portal — or maybe players start signing contracts.

While the NCAA forbids using name, image and likeness money for recruiting purposes, the vast majority of the respondents in ESPN’s survey said they think those payments have become a black market used to recruit both graduating high schoolers and transfers. Like so many of college football’s changes, if the team you support is benefitting, you’re less likely to have a problem with it.

More than half of the people ESPN surveyed said they think that college football should split off from the NCAA and create its own oversight system. And it does seem odd that the organization overseeing the business of college football is also responsible for regulating collegiate volleyball. It’s easy to imagine some sort of college football tsar, appointed by a collective of administrators, charged with steering the sport like the commissioner of a pro league. Because the business is so big and so geographically diverse — and involves so many public universities — governmental oversight isn’t out of the question either.

Or if one or two conferences dominate the postseason for long enough, those schools could essentially form their own league. Maybe that league decides to pay its players, giving these juggernaut programs an enormous recruiting advantage that would only widen the quality of football being played in college. What’s now Division I college football could become a tiered landscape. The big programs would continue to grow. Schools like BYU would probably be caught on the cusp. And a lot of universities would be on the outside, looking in, forced to play a different game.

Now, I agree with the idea that the players risking their health and future for a game that generates this amount of wealth deserve some part of that money. Amateurism, especially at the biggest programs, has always been a myth. But as the NFL expands its footprint from Sundays and Mondays to Thursdays, Saturdays, too, will become more and more professional.

That means that the experience of playing for — or rooting for — a Texas or Michigan or Georgia would continue to look even less like those early days of college football, when the game was about community and still only one part of the multifaceted transition from childhood to adulthood.

Some people are eager to see the game transform, though. “It is important for all of us in business to recognize that we’re in a time of change,” then-Big Ten commissioner Kevin Warren told ESPN when it published its survey. “I think there’s two types of people in the world, that they look at change as a problem or they look at change as an opportunity. I’m one of those individuals that, when change occurs, I get excited about it. It’s really an opportunity for us to do a lot of things that people have thought about but maybe (were) a little bit reticent to do.”

But the Big Ten stands to benefit enormously from power consolidation. Other conference leaders, like ACC commissioner Jim Phillips, have warned about the dangers of moving too quickly.

The sport has become the focal point for the large communities that build up around universities both big and small. A home game at almost any school is now an on-campus festival.

One conference’s gain is another conference’s loss.

One thing most people in the college football world agree on: the game itself is as good as it’s ever been. Every year, the players get bigger and faster. The passes get more accurate. The offensive and defensive schemes get more complicated. There’s more money and time and intellect directed toward trying to win. And the separation at the very top of college football is palpable. Last year’s national champion, Georgia, battled SEC competition all season. When the Bulldogs faced the Big 12 champion TCU Horned Frogs in the final playoff game, Georgia won 65-7.

Interestingly, the game has gotten better at small schools, too. Tulane, Troy and the University of Texas at San Antonio were all ranked in the top 25 in 2022. Utah State alum Jordan Love was a first-round draft pick of the Green Bay Packers in 2020 and he’s expected to take over the vaunted starting quarterback role there this year. Wyoming product turned Buffalo Bills QB Josh Allen is one of the best — and highest-paid — players in the NFL. So far, some money has continued to trickle down to these programs. Though it’s not clear at all how long that will be the case.

Tectonic shifts can create mountains. But they can also widen chasms.

Just the beginning?

The first time Longhorns fans got to see Arch Manning play was in a 2023 spring scrimmage. Dozens of reporters gathered in Austin hoping to see how the lanky freshman would play against college talent.

He didn’t look great. While there’d been some speculation that Manning would compete for the starting job this season, he was the third stringer at the scrimmage. When he finally got to play, he seemed nervous, unsteady, outmatched — like a boy playing against men. (He completed fewer than half of his pass attempts, for a total of 30 yards.) In the burnt orange corners of the internet, there was immediate debate over whether recruiting Manning was one giant mistake.

Some parts of college football haven’t changed much at all.

How exactly Manning ultimately fares in college, how long he stays at Texas, how much he earns while there — it’s all still up in the air. Like so much of college football these days.

It’s entirely possible that, as the biggest schools and conferences continue making Saturdays look like Sundays, some smaller universities will shutter their football programs. While fans of the power schools watch their favorite teams become more mercenary, fans of some have-nots will lose their teams entirely. Though I don’t think that’s likely.

Maybe someday soon, schools caught on the outside of the colossal realignment won’t produce any first-round draft picks or preseason polling favorites. But absent the massive audiences, absent the giant cash injections, removed from the national relevance, it’s also possible that college football at these smaller schools becomes more like those early elite programs — though hopefully not so fatal. Maybe the game at those schools will be less commercialized, more about community. Maybe players and fans alike will be there solely because they love the sport, the atmosphere, the way it can still help young people develop into productive adults.

The truth is, anyone who tells you they know for sure what the future of college football will look like is lying. There are too many variables. The big shifts may just be beginning. And each move has aftershocks. There will be new rivals, new rules, potentially entirely new oversight.

There’s only one thing we know for sure about the future of college football: It’s going to keep changing.

This story appears in the September issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.