How money, drugs and a foreign embassy played parts in the murder of Haiti’s president

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Hours before a group of former Colombian soldiers raided the guarded hillside residence of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse under the cover of night in July of 2021, they were given new orders.

Their mission, a squad leader allegedly told them, had changed and was now twofold: Find and kill Moïse, and find and grab bags of cash at his house, according to newly disclosed details of the Colombian investigation into the July 7, 2021, killing that hurled an already politically unstable Haiti deeper into crisis.

The amount supposedly inside was between $45 million and $53 million, according to statements some of the jailed suspects shared with Colombian and U.S. investigators looking into the brazen killing. The substantial cash allegedly stashed inside the president’s home suggests that it may have provided additional incentive for the lowly paid former Colombian soldiers and Haitian presidential guards to allegedly carry out the deadly plot after being ordered to do so.

“The decision to kill the president surfaced the day before the actual killing. The Colombians were told that they had to do it. There is no indication that they resisted this order,” a Colombian source with knowledge of his South American nation’s probe told the Miami Herald in an extensive interview. “We believe they were going for the money.”

Other law enforcement sources in Haiti and South Florida who are familiar with the deadly assault said there were substantial amounts of cash and other valuables stolen from inside Moïse’s home in the upscale Pèlerin 5 neighborhood in the hills above Port-au-Prince on the night of his murder. But they could not confirm whether the amount was in the tens of millions of dollars.

Claims about the money were made by not only some of the 18 alleged Colombian gunmen imprisoned in Port-au-Prince, but by at least one other suspect in a statement to U.S. authorities. The suspect told U.S. investigators, who have an ongoing parallel investigation, that he was informed the money inside Moïse’s home was a payoff to Haiti’s leader from drug traffickers who were using his country as a shipment point for Colombian cocaine destined for the United States.

Like Colombian investigators, U.S. authorities, however, have shown no interest in pursuing allegations that the money — or the president’s murder — could be interconnected in some way, possibly through drug traffickers who weeks before the assault were landing planes on one of the three airstrips located in an expansive, unpoliced savanna, known as Savane Diane, northeast of the capital, according to several sources. But the notion that Moïse, who knew about the airstrips and the drug drops, might have been killed because he planned to turn over a list of major narco-traffickers to U.S. authorities has also been rejected by investigators as untrue, according to several sources.

Suspicions about drug trafficking playing a role in the president’s murder were raised in a 124-page Haiti National Police assassination report first obtained by the Miami Herald. But, like U.S. investigators, Haitian police did not pursue any leads linked to narcotics.

Jailed Colombian suspect Alejandro Giraldo Zapata told Haitian police, according to the report, the assassination of Moïse was premeditated. He cited statements made by Duberney Capador Giraldo, who described the president as someone who “deserved this fate for having been a dictator, a drug trafficker who federated armed gangs.”

The report also noted that some of the other accused Colombians admitted to having spirited off with two bags filled with cash, documents, passports, checkbooks and assault rifles confiscated from presidential guards who were on duty the night of the deadly attack.

The report cites two currently jailed Colombians, Alex Miyer Peña and Carlos Yepes Clavijo, noting that they at one point had possession of the bags, which the Colombian source said were later in the possession of Capador.

“At the end of the attack, which cost the life of the President of the Republic, these armed individuals completely ransacked the room of the Head of the State, stole documents, large amounts of money and various objects, including the server of surveillance cameras,” the Haiti police report said.

The report doesn’t say how much cash was taken. The Colombian source said he cannot confirm whether the amount of $45 million that Colombian investigators were told about was “true or untrue.”

“That is what they claimed and we do not know where that money came from,” the source said.

The Haitian, Colombian and U.S. investigations into Moïse’s death were launched shortly after the assault that left the 53-year-old president with 12 bullet wounds and his wife, Martine, seriously wounded.

More than 40 people are currently jailed, including 18 Colombians in Haiti and three Haitian Americans with ties to South Florida as well as members of the Haitian presidential guard accused of taking bribes to stand down or not show up to work. Of the 30 guards who were supposed to be working that day, only seven were known to be on duty.

The only formal charges in the killing so far have been filed in the United States. Federal prosecutors in Miami have charged a former Colombian soldier, Mario Antonio Palacios Palacios, known as “Floro”; an ex-senator from Haiti, John Joël Joseph; and a convicted Haitian drug trafficker, Rodolphe “Dòdòf” Jaar, with conspiracy to kidnap or kill the president of Haiti. They have pleaded not guilty and are being detained without bond at a federal detention center as they await trial next March in Miami federal court.

Prosecutors and federal agents in Miami also have their sights set on charging three Haitian Americans — Christian Emmanuel Sanon, James Solages and Joseph Vincent — for their alleged roles in the plotting of the deadly coup. Also in the U.S. cross hairs: a few of the Colombian raid leaders, according to multiple sources familiar with the U.S. investigation. They are all in custody in Haiti.

But transferring any of these suspects to Miami has been challenging because of the political sensitivity of the assassination case in Haiti, Washington and Colombia. Complicating matters further has been the high turnover of investigative judges presiding over the criminal case in Haiti, with a fifth judge, Walther Wesser Voltaire, recently conducting a new round of questioning with suspects in custody.

Among them, two jailed top Haitian security officials, Jean Laguel Civil and Dimitri Hérard, who were responsible for Moïse’s security the night of his murder and were called by the president to send reinforcements. They are accused of internal complicity or inaction by police investigators. The judge also heard, for the third time in less than a week, from former police chief Léon Charles, currently Haiti’s permanent representative to the Organization of American States. He had Charles and Hérard, the former head of the National Palace’s General Security Unit, confront one another during questioning and then Charles and Laguel, Moïse’s security chief, in an effort to decipher what happened.

Under Haiti’s legal system, the investigative judge acts as a prosecutor and directs the police investigation while his secret inquiry is akin to a grand jury. Also recently questioned by Voltaire, who was appointed in May and has surpassed his three-month deadline to bring formal charges, were jailed Haitian Americans Sanon, Solages and Vincent.

Vincent’s defense lawyer, Regina de Moraes, shared her client’s text messages after he met with Voltaire the Wednesday before Thanksgiving Day. In those texts, Vincent said the judge asked him where he was in the hours before the president’s assassination.

Vincent, 57, said that on July 6, he was on his way to drop Solages off at the airport in Port-au-Prince when he received a call from ex-senator Joseph, who also goes by Joseph Joël John, to talk about an economic development project in Haiti. Vincent turned around and he and Solages, 37, drove to the ex-senator’s home. There, Vincent said he met with the politician and another associate, Joseph Félix Badio, a former consultant in the Ministry of Justice and a fired functionary in the Haitian government’s anti-corruption unit.

Badio, who also worked as a consultant for a security company in Port-au-Prince, remains in hiding. He is alleged to be one of the plotters behind the killing of the president, but he has not been arrested or questioned by authorities in Haiti.

Vincent said he told the judge during questioning that he didn’t know anything “whatsoever” about the plot to kill Haiti’s president, saying he was only aware of a plan to remove him from office. Vincent and Solages were on the grounds of the president’s home on the night of the assassination, and Solages falsely yelled as shots were fired that the raid was part of a Drug Enforcement Administration operation. Vincent, who once was an informant for the DEA, turned himself in to the Haitian police following the assassination on the advice of the in-country DEA supervisor after reaching out to his previous handler. Solages also turned himself in to police.

In the days after the slaying, Colombia’s national intelligence directorate and the intelligence director for the national police traveled to Haiti with Interpol to help with the investigations. Former Colombian President Iván Duque, in a recent interview with the Herald, said his country’s intelligence agencies, which arrived ahead of FBI agents, “were able to clarify things in a fairly short amount of time and that also allowed us to clarify many issues about the execution of the murder.”

However, there is one question that Colombian investigators were not able to resolve: Who the intellectual author of the crime was.

“That’s a topic where we have met ... with great obstacles in Haiti,” Duque said. “It is because there were many interests. But further investigation has not been allowed, and I do believe that this investigation has to get to the bottom [of that] because we’re talking about a political crime where there is participation and the presence of very powerful actors in Haiti.”

No one, the former president said, would risk entering a foreign country to assassinate a president “unless someone has given them guarantees that, after doing such a barbaric act, they were going to have some level of protection, and surely something went wrong with the plan.”

Duque did not go into details on how Colombian investigators, who were deployed within days of the assassination and given full access to the jailed suspects, were blocked. There were reports at the onset of the investigation of tensions between Haitian police and outside investigators. Despite that, the FBI, which has an agent stationed in Haiti, has continued its examination. Haitian police, meanwhile, have been forced to await orders from the instructing judge to proceed with their investigation after turning the case over to the judiciary.

“I hope that with the support that has come from the FBI and other federal authorities from the United States we will quickly know who were those involved and what was their motivation,” Duque said.

Duque said the 22 Colombians who traveled to Haiti did not have criminal records, and had served in the country’s military. Ahead of arriving in Haiti, he said, they left a trail of evidence, from online payments to the purchase of airline tickets.

But finding out more about their time in Haiti proved difficult for investigators, who have since turned over their findings to the FBI.

“In the moment the events occurred, it’s clear that what they were doing was not legal and not legitimate,” Duque said. “Also, everything indicates that there were people who had information a bit more detailed and they knew what the goal was.

“And curiously, in their own testimonies, the people who had the highest level of information died; so clearly there is a desire to cover up the intellectual truth.” He was referring to the squad’s co-leader, Capador, who was killed in a police shootout.

Motive remains a mystery, but was money a motivating factor?

The motive for the assassination of Moïse, a controversial head of state who had been ruling by decree for more than a year, remains one of several mysteries nearly a year and a half after the attack sent shock waves around the world.

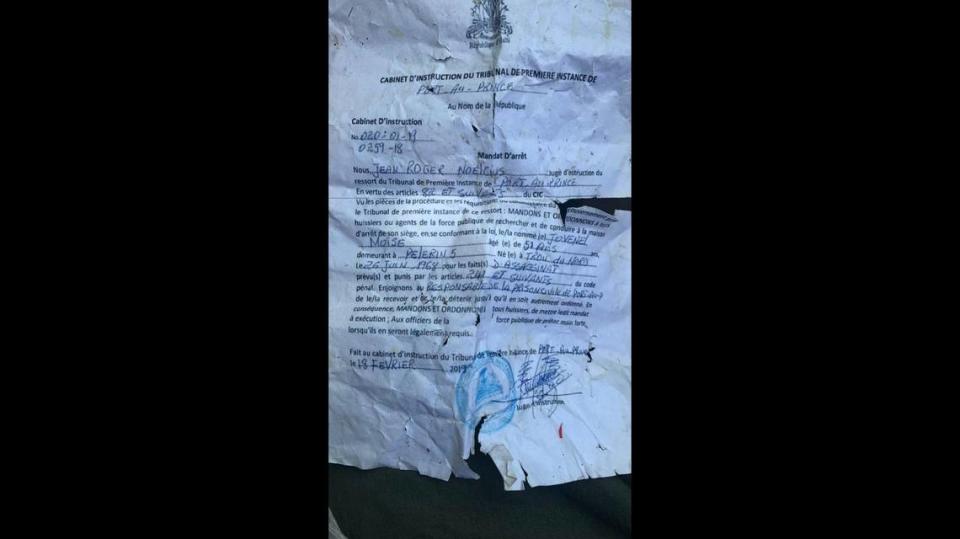

However, new details from the source familiar with the Colombian investigation paint a picture of a deadly coup and money heist, the latter of which may have been the motivating factor for the squad of former soldiers to kill Moïse. Those details also explain with greater clarity how nearly a dozen of the Colombians ended up inside the Taiwanese Embassy after the president’s murder before being captured by Haitian police.

After arriving in Haiti in early June, following a three-day stay in the Dominican Republic, the Colombians would go without receiving a monthly payment up to $3,000 that they had been promised when most responded to a WhatsApp posting about a security job in Haiti.

The amount was a king’s ransom in Colombia, where Palacios, during his first appearance in Miami federal court after being arrested, said his monthly income was the equivalent of $367.87 from his military pension.

Multiple sources have told the Herald that despite the promised salary for the Haiti gig, the Colombians had not been paid ahead of the assassination.

The Colombian source familiar with his country’s investigation said that heavy duffle bags of money stored on the second floor of the president’s home provided a major incentive for the Colombians to participate in the middle-of-the-night attack. He said the group’s leader, Capador, told them about the cash inside the house.

“They were told that the Colombians would get to keep $18 million of the $45 million, and the rest would be handed over to the Haitians,” the Colombian source said. “They never found out which of the Haitians would receive that money because Capador died.”

Capador allegedly took off with the bags of cash after the killing, but he died in an exchange of gunfire with Haitian police officers. His co-leader, Germán Rivera Garcia, a retired soldier known as “Col. Mike,” is currently imprisoned in Haiti.

The source confirmed that the coup plot started out as a plan to kidnap and arrest Moïse upon his return from a visit to Turkey in mid-June 2021, but that didn’t pan out.

Some of the Colombians were under the impression that they would be joining the new government charged with running Haiti after Moïse’s arrest. That government would have been headed either by Sanon, the South Florida preacher and doctor, whose supporters had launched a letter-writing campaign months earlier for him to head a transition government, or Haitian Supreme Court Justice Windelle Coq Thélot.

Moïse had illegally fired Thélot, and two other Supreme Court judges, in February of last year after announcing a foiled coup attempt. Thélot, in an interview with the Herald while in hiding, denied any involvement in the plot, but both Haitian police and the Colombian investigation allege that she met with some of the Colombians prior to July 7 and went by the code name “Diamante” or Diamond.

The Colombians had been told they would be accompanying local authorities and agents from the DEA on an operation to serve a purported warrant for the arrest of the president. Some were still under that impression on the night of the attack, according to two Colombian sources.

But hours before the attack’s launch, Palacios and four others who made up what Haitian police described as the “Delta team” were given new instructions, according to U.S. court records. In taped statements to U.S. federal agents while in custody in Jamaica, where he ended up after months of hiding in Haiti, Palacios said he learned on July 6 that the mission had changed from arresting Moïse to killing him.

A U.S. criminal complaint for Palacios’ arrest said some of the alleged plotters were actually aware by June 28 of the plan to kill rather than arrest Moïse before the assault was carried out 10 days later.

In addition, according to the complaint, Palacios said that a person identified as “co-conspirator #1” was “one of the leaders of the operation.” The Herald has learned from multiple sources that the person is Solages.

Palacios’ Miami attorneys are currently trying to get his confession about the plot thrown out based on the argument that he was not properly informed of his constitutional rights.

Alfredo Izaguirre, a Miami attorney representing Palacios, said that his client was in the president’s home, but not in his bedroom, where Moïse was fatally shot in a hail of bullets. The Colombian source and at least one other Haitian investigator who spoke to the Herald dispute that account, saying statements from Colombians in custody place Palacios inside the bedroom.

After Moïse’s murder, the Colombians came up with a makeshift plan to seek refuge in the nearby Taiwanese Embassy, protected by high walls and located across a two-lane blacktop from the president’s home. The Colombian leaders discussed the plan with the owner of a Florida-based security firm, Counter Terrorist Unit, or CTU, Security, the source said. CTU Security had chosen the Colombians to provide bodyguard services for Sanon while he was in Haiti.

CTU Security’s owner, Venezuelan émigré Antonio “Tony” Intriago, has not been charged in the assassination plot, nor has his business partner, Arcángel Pretel Ortiz, whose sister company, CTU Federal Academy, allegedly did the recruiting of the Colombians. Intriago’s Doral office — along with that of a Weston financier, Walter Veintemilla, who provided a loan through Intriago to Sanon — has been searched.

Through their lawyers, Intriago and Ventemilla have both distanced themselves from the assassination. Pretel, who once testified for the FBI in a Colombian drug cartel case and is believed to be an FBI informant, has not been heard from since the assassination. There is no evidence that he was acting on orders from the FBI, which declined to comment on whether Pretel was and remains an informant.

Gilberto Lacayo, a Miami lawyer who represents Intriago, said his client “was offered an opportunity to help rebuild the country of Haiti” and provided security services for Sanon, 64, in his quest to become the country’s next president. But Lacayo said Intriago “was never aware of any scenario” to kill Moïse.

Lacayo declined to comment on his client’s alleged role in collaborating with the Colombians to find refuge in the Taiwanese Embassy after the president’s killing.

But according to the source familiar with the Colombian investigation, Intriago was on the phone with the Delta force leader, Capador, soon after the attack instructing him to have the men go hide out at the embassy.

“They saw Capador calling Intriago and talking to him,” the source said. “Capador told them he was coordinating for them to have political asylum at the Taiwanese Embassy, so they would be protected. They also called [ex-Sen. Joseph] asking him to intercede for them at the churches, asking them to help spare their lives. These efforts were made by Capador and also Rivera, who was at another location.”

In the end, the men forced their way in, the source said, breaking doors and windows to gain access.

An official with the Taiwanese Embassy, speaking to the Herald on the condition of anonymity because of the ongoing investigation, said no one in the mission had had any contact with any of the suspects in the murder plot either on or before July 7. The official also said that the embassy staff was just as surprised as anyone else when they learned of the break-in by men in military gear. They received a 6 a.m. call from the Haiti National Police on that Thursday morning July 8, asking for permission — which they gave without hesitation — to enter the building to capture the 11 Colombians hiding there overnight.

According to statements provided to Colombian investigators, who arrived in Haiti ahead of FBI agents, when the group left Moïse’s residence at around 3 a.m. Wednesday, they found the streets near his house blocked by police.

The men then split up, going from house to house, to see if they could hide or find an escape route out of the hillside enclave just east of Pétionville, a Port-au-Prince suburb, off a mountain road. Soon, they found themselves exchanging gunfire with not just cops but well-armed gang members.

“That lasted until after noon,” the Colombian source said. “They entered different houses, some of them left their weapons, others began to turn themselves in, others fled, like Palacios did. And the majority entered the Taiwanese Embassy.”

The source said the Colombian gunmen and the two Haitian Americans who had accompanied them, Solages and Vincent, had not foreseen that they would be trapped within the limits of Pétionville, nor did they foresee the involvement of armed criminal gangs.

Michael Wilner of the McClatchy Washington Bureau contributed.