Monoclonal antibodies were 'doing nothing' against omicron: That's why FDA pulled its authorization.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Food and Drug Administration pulled its authorization of two of the most used monoclonal antibodies to treat COVID-19 this week, leaving doctors with fewer options to help their patients avoid the hospital.

Why did the FDA shut them down?

Because the two, from drugmakers Regeneron and Eli Lilly, don't work against the omicron variant that now causes more than 99% of coronavirus infections in the United States.

"All the data show that these older antibodies are ineffective against omicron," said Dr. Daniel Kuritzkes, chief of the division of infectious diseases at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston.

It was clear that for patients with omicron infections the monoclonals were "doing nothing," said Dr. Eric Topol, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, California.

"There's overpowering data (that these) monoclonals are unable to bind to omicron," he said.

So, now what?

How widespread is use of remdesivir, other monoclonal antibodies?

The government in November nearly doubled its order for a third monoclonal antibody, sotrovimab, made by GlaxoSmithKline and Vir Biotechnology. The U.S. has now spent $1 billion buying the drug, which, according to studies conducted before omicron, can reduce the risk of hospitalization for more than a day by 79%.

In mid-December, the government said it was preparing to ship out 55,000 doses of sotrovimab nationwide.

Doctors said this would help, but the number of high-risk patients with COVID-19 who could benefit from the drug far exceeds the supply. The entire state of Louisiana, for instance, only got 228 doses.

OMICRON'S NEW VARIANT COUSIN, BA.2, HAS ARRIVED IN U.S.: But don't panic, experts say

Roughly 40% of Americans are considered at high risk for severe disease because of their age or health status.

The FDA also has authorized the drug remdesivir, which had been used only on hospitalized patients, to be given to those at risk for hospitalization earlier in the disease course.

The drug has been shown effective for outpatients, reducing the risk of hospitalization and death by 87% compared to a placebo. It can be tricky to deliver because it must be given by infusion three days in a row, but could be useful particularly for people in a nursing home or can otherwise easily access medical care three days in a row.

It also can be used in high-risk children ages 12 and up who weigh at least 88 pounds.

What are monoclonals, and how do they work against COVID-19?

Monoclonal antibodies are engineered proteins originally derived from patients who beat the disease.

They target and bind to specific spots on the virus, preventing it from entering human cells.

But when those spots on the virus change with new variants, the monoclonals no longer work. The Regeneron and Lilly monoclonals consisted of two monoclonals each, to try to avoid that problem, but omicron has differences in exactly the areas targeted by both.

"It doesn't mean they're dead forever," Topol said. "They could have a comeback with the next variant, but we don't know what's ahead."

Monoclonal antibodies for COVID-19 have all been authorized for emergency use, so the FDA can withdraw permission for their use at any time if they prove unsafe or ineffective. Drugs authorized under emergency use have to pass fewer hurdles than fully licensed drugs, though they must still be shown to be safe and effective.

Can monoclonal antibodies be a substitute for COVID-19 vaccines?

No. For several reasons.

First, vaccines are designed to prevent infection, while monoclonals and other treatments are aimed at people who are already infected.

The odds of avoiding severe infection are far better with vaccination than with trying to treat "once the horse is out of the barn," Topol said. "It's a roll of the dice that one of these treatments, which are hard to get, are actually going to work."

A VACCINE SPECIFICALLY FOR OMICRON? Pfizer and BioNTech announce plans to test in adult trials

Even the most effective of the treatments, Paxlovid, only prevents 90% of severe infections and deaths, he said, while vaccines prevent closer to 99%.

Timing also matters with treatments, which have to be given within about 5 days of symptoms appearing and require a prescription.

While vaccines can help prevent the spread of the virus that causes COVID-19, treatments do not reduce spread.

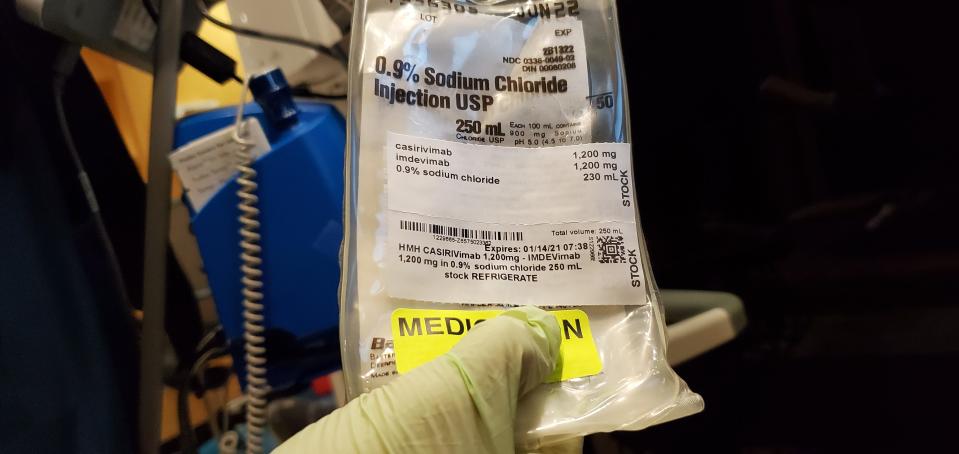

Also, monoclonals are about 50-times more expensive. Although both are provided free by the federal government, vaccines cost less than $20 per shot and monoclonals $1,200, without counting the need to set up an infusion center to provide the antibodies.

What can doctors do to keep COVID-19 patients out of the hospital?

While no one can know with certainty who will get a bad case of COVID-19, vaccines have been shown to be extremely effective at preventing severe disease, hospitalization and death.

A monoclonal antibody called Evusheld from AstraZeneca has been shown to prevent severe disease in people with weakened immune systems, who may not get full protection from vaccines. It provides long-lasting protection, but with 700,000 doses on order from the federal government, it won't help the vast majority of 7 million immunocompromised Americans who could benefit from it.

'TIRED, BURNED OUT, FRUSTRATED': Omicron surge hits nursing homes as vaccine mandate looms

There also are two new promising antiviral drugs, that come as a five-day course of pills that can be taken at home. But authorized only late last year, they will continue to be in short supply for most of this year.

Both have their strengths and weaknesses.

Paxlovid, by Pfizer, prevents nearly 90% of COVID-19 infections from becoming severe, research shows. A combination of an antiviral and an HIV drug that makes it work more effectively, Paxlovid can interact with a number of other medications, which may need to be stopped during the five-day treatment.

Molnupiravir, made by Merck and Ridgeback Therapeutics, should be a second choice, a federal advisory committee decided in December, though it is likely to be more widely available than Paxlovid, at least for the next few months. Studies suggest it is less effective and should not be taken during pregnancy.

Neither has been authorized for use in children.

What comes next in supply chain?

More monoclonal antibodies are winding their way through the FDA's authorization process, which will eventually increase supply.

As the virus continues to evolve, though, it's possible that even newer ones will be needed to target new variants.

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: FDA bans two monoclonal antibodies over omicron variant. Here's why.